Peak Car Poses a Mortal Threat to Germany’s Most Important Industry

Automotive employment in Germany will start to decline this year.

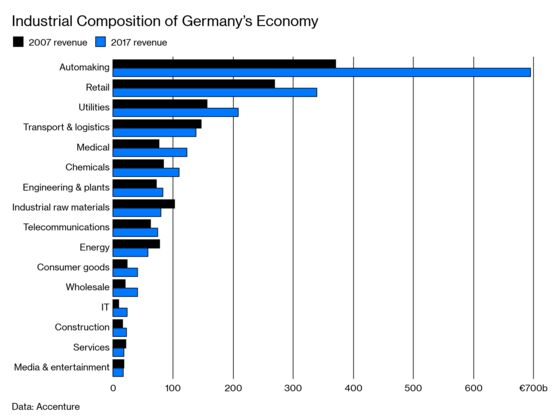

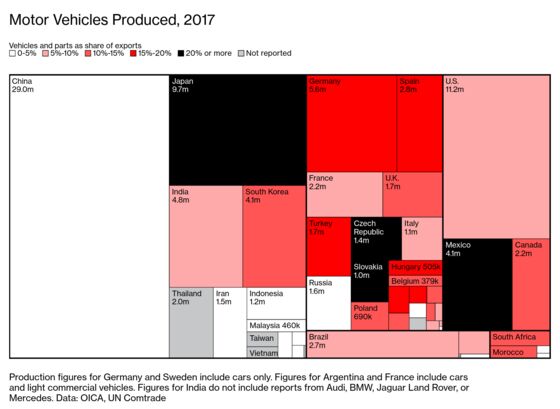

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Germany is the birthplace of Karl Benz, the inventor of the automobile, and gave rise to the “People’s Car,” Volkswagen, which has grown into the world’s biggest auto manufacturer. It’s home to four brands—BMW, Mercedes, Audi, and Porsche—that account for 80 percent of global sales of luxury vehicles. And with 835,000 workers, the auto industry is Germany’s biggest employer, responsible for a fifth of the country’s exports.

But automotive employment will start to decline this year, the powerful IG Metall union predicts. Germany may have reached peak car, posing a threat to the most important pillar of the economy. “We’re preparing for a time when fewer people will work in the industry in our region,” says Rüdiger Schneidewind, mayor of Homburg, a western city of 42,000 with four big factories that account for 30,000 jobs. “More than half of this region’s prosperity is due to auto manufacturing.”

It’s hard to overstate the degree to which the automobile permeates German culture. The country’s no-speed-limit autobahns are the stuff of legend, and the cars that run on them are technological marvels supporting a vast ecosystem of suppliers and developers. But as people shift to ride-hailing, car-sharing, and driverless electric vehicles, many of Germany’s advantages will evaporate. “The three core features of mobility in the 20th century are dissolving: cars that need a driver, are privately owned, and are powered by a combustion engine,” says Stephan Rammler, an auto industry consultant and professor of transportation design at Braunschweig University of Art. “Germany risks falling behind new giants being created in China and the U.S.”

The concern for the Germans is that profits will flow increasingly to arrivistes such as Waymo, Apple, or Uber Technologies. Battery-powered cars don’t need as much precision engineering as traditional models, and making them will require fewer workers. More than a third of Germany’s 210,000 jobs in engine and transmission production will disappear by 2030, IG Metall says. “Carmakers can only survive as mobility-service providers, not as auto manufacturers,” says Horst Lischka, IG Metall’s Munich head and a member of BMW AG’s supervisory board.

Unlike in the U.S., where the industry is concentrated in a handful of regional strongholds, automaking in Germany is a nationwide endeavor: Volkswagen is headquartered in Wolfsburg, 140 miles west of Berlin. BMW and Audi have offices and factories across the southern state of Bavaria. Daimler AG and Porsche are based in Stuttgart in the southwest. A bit farther north, in Cologne, Ford Motor Co. employs 17,500. And around Homburg, near the French border, suppliers such as Bosch, ZF Friedrichshafen, and Schaeffler make everything from transmissions to diesel injectors to pistons. Workers are typically well-compensated: Manufacturing jobs pay about 20 percent more than those in services, providing a ticket to the middle class for hundreds of thousands of people with only a high school diploma.

Even places with little history of auto manufacturing have embraced the sector. The former East German state of Saxony had no modern vehicle production before the Berlin Wall came down. Then in 1991, VW started making Golfs in Zwickau, three hours south of the capital on one of the world’s first superhighways, built in 1930s by the Nazi regime. In 1999, Porsche opened a plant near Leipzig where it makes Macan SUVs and Panamera sedans. And in 2005, BMW inaugurated a facility near Leipzig designed by Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid; it was hailed at the time as the world’s most advanced factory. Today the three companies and their suppliers employ 95,000 people in Saxony and account for a quarter of the state’s industrial output.

While German automakers have announced ambitious electric-vehicle programs to stay ahead of the transformation, the shift hasn’t been smooth. VW will spend €1.2 billion ($1.4 billion) retooling Zwickau to make a half-dozen electric models by 2021—but it warns that the payroll is likely to shrink. Three years ago, the carmaker created the Moia brand to spearhead its push into 21st century mobility; in December it wrote off the unit’s $300 million investment in ride-hailing startup Gett Inc. BMW and Daimler each created car-sharing units, but after struggling to turn a profit they merged them last year. The new brand, Share Now, will oversee the companies’ combined car-sharing operations as well as initiatives in charging EVs and apps to help drivers find parking spots and taxis. “There’s plenty of opportunity,” BMW Chief Executive Officer Harald Krüger told Bloomberg TV. “It’s an important amendment to our core business. You have to have these services.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.