Paper Mail Still Matters to People Behind Bars

Paper Mail Still Matters to People Behind Bars

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Mail call on Thursday, Sept. 13, was different from any other in Sheena King’s 26 years behind bars. As usual, the unit officer came to her door. But instead of handing her an envelope with a letter inside, he handed her four photocopied pages stapled together. “The first page is a copy of the front of your envelope,” King wrote in response to emailed questions from Bloomberg Businessweek. “The second is a copy of the back. The third page is blank and appears to be a copy of the back of your letter. The last page is the actual letter.”

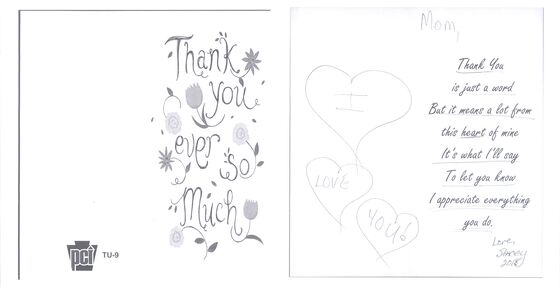

On Sept. 5, Pennsylvania became the first state in the U.S. to eliminate personal mail in its prison system. The policy means that its prisoners can no longer receive birthday cards, handwritten notes from Grandma, or drawings from their children. Instead, their families send mail to the offices of Smart Communications U.S. Inc. in St. Petersburg, Fla., where, says Chief Executive Officer Jon Logan, employees inspect each piece of correspondence before converting it into a searchable electronic document. The company sends the digital files to the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, where prison officials can review the contents before delivering them as black-and-white printouts to their intended recipients. Each piece of correspondence becomes part of a searchable database, guaranteeing prison officials perpetual access, even years after the recipients have been released.

Prisons throughout the U.S. have tightened restrictions on what can and can’t be sent through the mail, to combat the flow of drugs from the outside world to incarcerated individuals. Some states have banned colorful envelopes, greeting cards, and even computer printouts. But Pennsylvania’s prison system is the first to fully eliminate personal mail.

Started in 2009, Smart Communications provides technology to correctional systems, including e-messaging, a limited form of email that King uses, and video visiting, a teleconferencing system that some prisons have adopted in place of in-person visits. In 2016, Smart Communications unveiled its MailGuard system, touting it as the first system to fully eliminate postal mail in jails.

Today, Logan estimates that of the 100-plus state correctional agencies and county facilities that contract with Smart Communications, about half use MailGuard, and he’s in discussions with at least a half-dozen more. To accommodate the increased mail volume, the company recently bought a 20,000-square-foot warehouse and added 40 employees. Logan wouldn’t comment on the company’s finances, but a copy of the contract obtained by Bloomberg Businessweek shows that the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections has agreed to pay Smart Communications $376,000 per month for its services through July 2021.

Prison spending has ballooned since the mid-1980s, when the incarcerated population was less than a third of what it is today. Overflows in state-run facilities led to contracts with private companies, which provide services such as food, telephone, and medical care, sometimes sacrificing prisoner comfort and safety for cost efficiencies. According to the Corrections Accountability Project at the Urban Justice Center, more than half of the $80 billion spent annually on incarceration flows to private companies.

Bianca Tylek, director of the Corrections Accountability Project, calls digitized mail services a “tremendous growth opportunity” for private companies seeking to contract with prison and jail systems. Using Pennsylvania’s 27 prisons and almost 48,000 prisoners as a gauge, Tylek estimates the nationwide market for mail processing could be more than $180 million annually. She also cautions, “Because it’s early in the game, Pennsylvania is probably getting a better deal.”

For King, who’s been in prison since the age of 18 for a murder she says she was pressured into committing, mail has been her lifeline. “Most of our families are a great distance, and phone calls keep us connected, but when your 15 minutes are over, that letter or card is what keeps you grounded,” she wrote. “When I hold a letter from my children, my mother, my niece, or my man, there is a connectedness that I feel just seeing their handwriting. I won’t feel that with a lightly photocopied version. What color was it? What kind of design was it? You can’t tell, because it’s faded.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Eric Gelman

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.