Package Tours Are No Picnic. That’s Not Stopping Germany’s TUI

Package Tours Are No Picnic. That’s Not Stopping Germany’s TUI

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For decades, tour operators such as TUI, Kuoni, and Thomas Cook thrived by offering package holidays to sun-starved Europeans put off by unfamiliar tongues, foreign currencies, and hotel reservations made from afar. But these days the euro has eased money concerns, discount airlines will fly northerners to warmer climes for as little as the cost of lunch, and beachfront accommodations are just a few mouse clicks away—no language skills needed. At the same time, terrorism, political turmoil, and hotter summers in the north have kept many would-be travelers at home.

The shift has squeezed profits at tour operators and forced long-standing players from the field. French stalwart Club Med went on the block in 2015 and ended up in the hands of Fosun Tourism Group from China. Switzerland’s Kuoni in 2015 sold its tour operations to a German supermarket chain after offloading its business travel and airline units. Thomas Cook—which invented the package holiday in the 1840s with train trips through the English Midlands for temperance activists—said in July it would sell its consumer tourism business to Fosun after its bonds fell to one-third of face value.

The one exception: TUI, a century-old German company with roots in mining. After branching out into goods ranging from chemicals to toothbrushes, in 1997 it bought German freight line Hapag-Lloyd, which owned a handful of cruise ships and a package-tour unit called Touristik Union International. The idea was to abandon heavy industry and focus on tourism, and the company changed its name to TUI in 2002. “When rivals are in trouble, you always have to ask yourself: Is that because they’re performing poorly, or is the industry getting more difficult?” says Fritz Joussen, TUI’s chief executive officer. “The industry has become more difficult, and that’s why we began to transform.”

It’s been a bumpy road, with investors criticizing management for missing earnings targets and selling industrial assets too cheaply while overpaying for an ill-timed foray into container shipping. The company even held a controlling stake in Thomas Cook for 15 months but was ordered to sell it in 2000 to comply with antitrust rules. While TUI still needs to prove the package-tour business can thrive longer term, says Richard Clarke, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein, the strategy shift has steered the company in the right direction. “TUI has evolved enormously,” he says. “It’s also suffering, but it has managed to adapt.”

Key to TUI’s resilience has been going upmarket and adding exotic destinations while getting closer to customers and controlling more of the revenue they generate. Whereas Cook serves mostly as a booking service, paying for blocks of rooms at a discount and reselling them to clients, TUI owns or manages 380 hotels with a total of more than 240,000 beds, up 60% in the past decade. And with Hapag-Lloyd, it picked up a handful of ocean liners, not traditionally a big business in Germany. “We asked ourselves: Should we sell the cruise business or try and turn it around ourselves?” says Sebastian Ebel, the TUI executive responsible for hotels and cruises. “We went with the turnaround.” Today, TUI has 17 vessels, from 150-passenger craft for Amazon or Arctic excursions to 2,900-bed behemoths with sumptuous suites, swimming pools, and multiple restaurants.

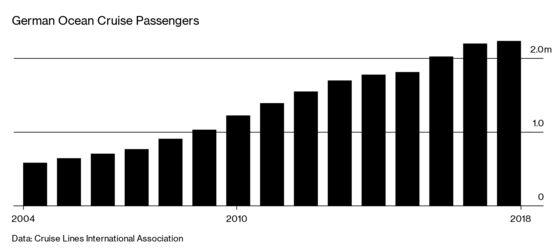

In its home market, TUI sensed an opportunity. Cruises weren’t popular in Germany, but the country’s prosperity, generous vacation policy, and aging population suggested they could become a big business there. In the past decade the number of Germans taking cruises has more than doubled, to 2.2 million a year. The business helps even out cash flow, because unlike hotels, ships can move south to keep earning in the winter months, and passengers often pay earlier than summer holidaymakers do.

TUI further reduced seasonality by adding hotels in year-round destinations such as the Caribbean and started filling them with nearby North Americans brought in via expanded ties with U.S. travel agencies. The shift hasn’t been cheap: A resort big enough for package tourists can approach $100 million, and a large cruise ship costs many times that. TUI’s annual capital expenditure has doubled, to $800 million, in the past five years.

Myriad dangers remain as travelers flock to online reservation sites. Booking Holdings, owner of Booking.com and Priceline, has a market value of $77 billion—more than 10 times TUI’s. Vacationers want more personalized experiences, such as those offered by Airbnb, which has 6 million-plus listings. And airlines are teaming up with hotels and rental car companies to offer many components of package tours. With tens of millions of passengers a year, “it’s now our job to get them to book their entire holiday with EasyJet,” Johan Lundgren, the carrier’s CEO and a veteran of TUI, told analysts in May.

Yet TUI insists its strategy is sound. Today two-thirds of profit comes from cruises and hotel ownership, twice the level of five years ago. The company is planning a big push in Asia to attract Chinese and Indians to beach destinations. It has nine hotels from the Maldives to Thailand and aims to more than double that in the next few years. And it plans to step up sales of extras such as snorkeling trips, four-wheel-drive outings, or guided city tours, a business it estimates is worth $150 billion a year. “We have a great chance of success,” CEO Joussen says. “We want to know every customer so well that we can offer them individual experiences.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.