How a Charity Superstar Innovated Its Way to Political Scandal

How a Charity Superstar Innovated Its Way to Political Scandal

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- One morning in early March, 12,000 schoolchildren and their teachers gathered in London for the world’s loudest field trip. Screams filled cavernous SSE Arena, the party a reward for good deeds done. Through a four-hour extravaganza of strobe lights and celebrity cameos, tween-age “change makers” bopped their way through dance and musical performances interspersed with motivational speeches. Singer Leona Lewis and Sophie Grégoire Trudeau, wife of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, talked self-empowerment. Formula One legend Lewis Hamilton spoke out, despite his day job, against climate change. There was a shoutout to Virgin Group Ltd., the main corporate sponsor. Obligingly, the kids waved their light sticks and roared.

The spectacle, known as a WE Day, was the brainchild of two Canadian brothers, Craig and Marc Kielburger. In the 25 years since a 12-year-old Craig started a charity devoted to ending child slavery, they’d added a for-profit wing and won over the young, the rich, and the powerful to an uplifting if sometimes controversial brand of do-goodism. Their philanthropic behemoth, WE Charity, had development projects in nine countries and was bringing in some C$66 million ($52 million) a year; its U.S. fundraising alone placed it in the top 5.5% of American public charities by revenue. Mentored by the likes of Oprah Winfrey and Richard Branson, the Kielburgers had galvanized Fortune 500 boardrooms, regulars at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, and thousands of schools. And their charity/business empire was unlike anything the philanthropic world had ever seen, featuring a for-profit voluntourism operation that hosted billionaires and politicians, as well as events that drew luminaries on the order of Prince Harry and Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

Within months of the London festival, though, WE Charity would be on its knees, and the Kielburgers would be facing an unfamiliar level of scrutiny. First, the novel coronavirus halted big gatherings and international volunteer trips, two pillars of the brothers’ business model. Then their talent for courting elites backfired, following a June announcement by Trudeau’s government that WE would be the sole administrator of a C$544 million Covid relief program offering grants to support student volunteers. It soon came to light that WE had been awarded the deal uncontested and had previously paid hundreds of thousands of dollars in speaking fees and expenses to Grégoire Trudeau and other Trudeau family members, setting off a controversy that would help unseat Canada’s finance minister and trigger an ethics investigation into the prime minister himself.

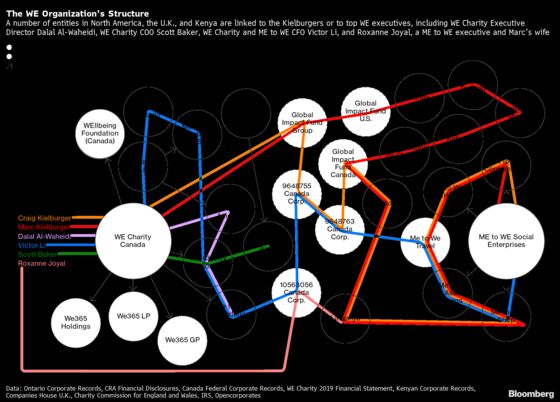

Journalists, opposition politicians, and others started taking a closer look at WE. They found that beneath its virtuous messaging lay a complex corporate structure that mixed philanthropy with for-profit activities and featured a dense web of political connections that held the potential for conflict of interest. Former employees also stepped forward with allegations of racism and exploitative behavior. The organization quickly backtracked from the government contract, but the damage was done. By fall the brothers were on TV, tearfully announcing the shutdown of their main philanthropic endeavor in Canada.

Still, the question remains: Whom did the charity benefit most—the developed or the developing world, the organization or those it intended to help? In interviews with Bloomberg Businessweek or in public testimony, ex-employees, former students and a teacher at WE’s charitable schools abroad, and others who’ve had close dealings with the Kielburgers allege a pattern of obfuscation and lackluster oversight, with unusually intricate corporate structures, funds spent on a real estate portfolio that was large for a charity, and pupils in impoverished areas used as props and sometimes subjected to corporal punishment by teachers.

In a 71-page reply to queries sent by Bloomberg Businessweek—accompanied by more than 400 pages of supporting materials, including third-party assessments, testimonials, employee statements, and a separate 22-page set of responses from its lawyers labeled “Exhibit 1”—WE disputed the criticisms and allegations that have been levied against it, including assertions that corporal punishment took place at one of its schools. The response stated that the organization’s complexity was dictated by Canada’s and other nations’ laws and regulations, that its real estate holdings and for-profit businesses were the best way to support WE Charity; that, far from being exploitative, its activities benefited many people around the world; and that some of its critics are disgruntled former employees and students.

How two brothers redefined philanthrocapitalism only to see their work collapse around them is still being untangled. But the fallout has shaken the development world, prompted accusations of white privilege, and exposed the insularity of Canada’s establishment that had for years ignored questions surrounding an organization that traded on liberal, progressive values.

It all started with two 12-year-old boys.

In April of 1995, Craig Kielburger was scanning the newspaper for cartoons as he ate breakfast in his suburban Toronto home when a story from Islamabad caught his eye. It was about Iqbal Masih, a boy who’d been sold to work at a Pakistani carpet factory, then escaped to become a prominent child activist. Masih had recently been murdered. He, like Craig, was 12.

The story shocked and inspired Craig, who rallied his classmates and Marc, five years his elder, to form a group called Free the Children. Child labor was one of the biggest trade policy issues of the 1990s, and Craig quickly developed a near-evangelical pull on his audiences. In a video of an impassioned speech to a convention of labor unions in Toronto in November 1995, he pauses at times with his eyes closed, effortlessly commanding the attention of 2,000 adults. When he concludes, labor leaders step forward to pledge money. He left the event with C$150,000, 15 times his stated goal.

Before long, Craig’s campaign to free child laborers from bondage came to international attention. He addressed U.S. congressional committees, appeared on 60 Minutes, and met with Al Gore, Mikhail Gorbachev, and Pope John Paul II. He wrote a book and starred in a documentary. (He also brought a libel suit at age 14, over a magazine profile, and later received a reported C$319,000 in a settlement.) Within three years, the brothers were running a global philanthropy, now with a focus on establishing schools in Ecuador, India, Kenya, and Nicaragua (though they kept the name Free the Children until 2016). In 1999 they founded a business that became a pioneer of voluntourism, selling service trips abroad.

That same year, at 16, Craig landed a spot on Winfrey’s famous set. “You have no idea what’s about to happen when this goes to air,” Tim Bennett, then one of Winfrey’s top executives, told the Kielburger brothers, according to a 2018 book they co-authored, WEconomy: You Can Find Meaning, Make a Living, and Change the World. In a spur-of-the-moment pledge, the talk show queen committed to funding 100 schools. She became a key mentor, introducing Craig and Marc to a more high-powered tier of philanthropy.

As Craig built the charity’s profile, Marc amassed diplomas—from an elite Swiss high school, then Harvard (international relations), then the University of Oxford (law). Spurning lucrative offers from Wall Street, he brought his world of elite connections back to the small charity that as of 2003 was still being run out of the Kielburgers’ living room. Craig had by then begun his undergraduate studies at the University of Toronto’s Trinity College. “He was sharp, motivated, impassioned,” recalls one of his former professors, David Welch. “He was also the only student I ever taught who asked for an extension so that he could travel to Sri Lanka to open a school and receive a prize.” An executive MBA followed.

By 2004, the brothers were looking for ways to generate stable revenue to counterbalance the vagaries of donations. They opened Bogani, a safari-style camp for volunteer travelers who paid to stay on the doorstep of Kenya’s Maasai Mara National Reserve. An eco-friendly T-shirt business soon followed. Those efforts would eventually crystallize, backed by a key investment from Jeff Skoll, the former president of EBay Inc., into ME to WE Social Enterprises, a for-profit business selling volunteer trips and fair-trade goods, such as beaded Maasai bracelets and chocolate made from Ecuadorian cacao, sourced from the charity’s overseas projects. ME to WE pledged to donate at least half its profits to the charity and touted the “highest of governance standards,” according to one press release.

Also in 2004, the charity launched an initiative, later named WE Villages, that expanded its purview from education to clean water, health care, and sustainable farms and other income-generating projects. The villages became destinations for volunteer tourists from ME to WE. Depending on one’s inclinations and means, a trip could entail two backbreaking weeks digging foundations someplace remote or a glamping excursion where the chore list was short and the wine list long. ME to WE started operating a string of luxury properties in Ecuador, India, and Kenya, which became base camps for wooing donors and celebrity ambassadors, as well as a source of local tourism jobs.

To underpin it all, the Kielburgers began refining a simple and seductive philosophy, one David Jefferess, a professor of cultural studies at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus, describes as consumption for the betterment of others. “We want to see ourselves as good people without having to give up, or risk, or sacrifice anything,” he says. “The language they use is fortune and misfortune. They don’t talk about privilege.”

In 2006 the Kielburgers and Winfrey teamed up to start providing North American teachers with curriculum aids—a program eventually sponsored by Dow Inc., Walgreen Co., and others—and encouraging students to set up fundraising clubs. The strategy got WE into thousands of Canadian, U.K., and U.S. schools. Staff would go out to give talks on various social issues, giving out mail-in slips the students could send back to the charity with their contact information, which it would use to offer kids guidance on pursuing their chosen causes. According to a post on the Medium platform by a former speaker named Matthew Cimone, the more that were returned, the better a candidate the school became for a major WE fundraising program. (WE says that it’s “cause inclusive” and that it encourages young people to fundraise for whichever ones they choose. A report the charity provided says that, in the current academic year, about half of WE-affiliated school groups raised funds, and four in 10 of them did so for WE.)

The charity also struck more than 50 media partnerships, covering ABC and Fox television, MTV, the Seattle Times, the Chicago Tribune, Facebook, Twitter, and most of Canada’s largest outlets. It all came together at its WE Day jamborees, which served to reward student activists, sell merchandise, and elevate the profile of the charity and its founders. The first WE Day was held in Toronto in October 2007, with a lineup that included Trudeau, then campaigning for his first parliamentary seat. The events grew in scale and glamour, expanding to more than a dozen North American and British cities annually. Corporate partners footed the bill, which could top seven figures. Celebrities donated time to speak for such unimpeachable causes as anti-bullying, self-empowerment, and equality. Sales booths and advertisements plugged ME to WE trips and trinkets, while a “Teacher Zone” offered educators ideas on how to fundraise.

Within three years of the first rally, WE Charity’s annual revenue had more than doubled, to C$22 million, and it had opened offices in Palo Alto, Calif., and London. Some 55,000 children in seven countries were studying in the 650 schools and classrooms it had built, and the Kielburgers could fairly claim credit for raising awareness about global poverty and embedding the concept of helping into educational curricula. Almost a half-million North American and British youth were active in affiliated clubs, and 36,000 children attended WE Days in 2010 alone.

As the charity grew, some people started to ask whether it was becoming more visible in the countries providing the money than in the places it had set out to help. The unease percolated among some development experts, teachers, academics, and even staff and donors. “Every year you answer more and more questions about WE Charity than any other,” says Kate Bahen, managing director of Charity Intelligence Canada, an independent researcher that conducts due diligence on nonprofits and began covering WE in 2011. The questions would center on the public face of WE Charity, she says. People wondered about its deep presence in schools and asked how $5,000 student trips and celebrity-studded youth rallies contributed to philanthropic work. Bahen’s own research indicated blurred lines between the charity and for-profit that could make it difficult to tell what share of revenues ended up where.

The tensions inherent to WE’s approach were perhaps nowhere more evident than at Bogani, the camp situated near the Maasai Mara, a few miles from “the strip,” a string of showcase projects that included a hospital, a college, and boarding schools for girls and boys operated by WE. Guests could have an Out of Africa-style experience, complete with colonial undertones, learning to throw Maasai “rungu” clubs or laying bricks before retiring to a beverage on a veranda overlooking the savanna and a sound night’s sleep in cozy cottages or luxury tents adorned with African fabrics and masks. A six-night stay, pre-Covid, was priced at $5,450 per person, with an optional $5,595 safari add-on. On a 2011 episode of MTV Cribs, Craig gave viewers a tour, swigging cow blood from a gourd before arriving at a simple wooden guest-cottage staircase, where he marveled, “God, it’s amazing what they manage to build in the absolute middle of nowhere, Africa.”

VIPs staying at Bogani could expect a tour of the strip, trying their hand at various chores before receiving a seemingly spontaneous blessing from a Maasai elder. After that, hopefully, would come a big donation or business partnership. “They create this highly curated, seemingly singular experience that is surely life-changing for the people that experience it but in reality is deeply problematic and scripted,” Sarah Koff, who formerly led WE’s California office and visited Bogani three times, said in a video posted this summer to Instagram. “But it gets people to donate, it inspires them.” (In its response to Businessweek, WE said that the trips are designed to be respectful of local cultures and that it would be incorrect to say that their purpose is “for any reason other than benefiting the community.”)

A former student, Branice Koshal, recalls being told after enrolling in the girls’ boarding school on the strip in 2013 that she would have to remain on campus, in uniform, during school holidays if they coincided with high season for VIP visits—to “entertain the guests,” as she puts it. “Our parents wanted us home, but because we were getting scholarships, they had no power to complain,” says Koshal, who’s now 22. “If they were paying fees, probably they could have boycotted.” (WE says meetings with volunteers and donors during holiday breaks were “optional opportunities.”) If guests arrived when school was in session, classes could be disrupted twice a day. Teachers had students rehearse for the 30-minute interactions over tea and mandazi pastries: show appreciation, say how much the schooling and materials had helped them, then solicit more help.

There was a grave taboo, Koshal says, that would land a student “in hot soup”: mentioning the canings students sometimes received. In her second year, she remembers, she was thrashed for not doing well enough on exams, one of what she describes as many such incidents. Two other former students, who asked not to be identified for fear of retribution, say they, too, were caned multiple times—on the back, the legs, the buttocks, the hands. Jointly, they say their experiences span from 2012 to 2016 on two separate campuses the girls’ school used at the time. A former teacher at the school, who also asked not to be identified, further confirmed that corporal punishment took place there during that period.

Corporal punishment was outlawed by Kenya’s 2001 Children Act, but a Unicef report from 2014 found that it remained common there afterward, and that teachers were among the most common perpetrators of violence against single girls. The students say it didn’t take much to incur the punishment: tardiness, an unfinished assignment, oversleeping. One recalls that in November 2015, her entire class was caned after some pupils were caught using a phone to prepare for their final exams. All three of the former students say that, despite such episodes, they’re grateful for the free education they received and the opportunities it created for them.

In responding to the allegations of corporal punishment, WE said that in its educational framework model, caning is “forbidden” and that there had never been a reported incident of caning at the schools it operates. “There was no ‘caning’, in any manner, taking place,” said a statement from Carolyn Moraa, the WE director overseeing the schools. WE also provided statements signed by a student, a parent, and a volunteer community leader that said they’d never heard of canings at the schools.

Former employees who requested anonymity because they’d signed nondisclosure agreements recount that Kenya projects were sometimes built as slowly as possible to ensure a steady supply of feel-good tasks for donor groups, which could number as many as 100 people. A running joke among staff was that donor plaques hanging on buildings should be made of Velcro because they were swapped so frequently. (Several ex-employees say this practice was eventually abandoned.) A wall at Baraka Hospital, the medical facility on the strip, was rebuilt at least four times by volunteers, according to three people with direct knowledge. The same three sources say that so-called community mobilizers cajoled villagers into donning traditional garb and cheering with requisite enthusiasm when donors arrived.

In one memorable incident recalled by former employees, a major benefactor came for the opening of a women’s empowerment center. The night before, Craig realized the donor had specified the center was to have a kitchen. Mayhem ensued. Employees were instructed to cobble together a makeshift kitchen with equipment from a nearby high school. Photographs of the result show pots and pans hanging neatly on the wall and tidy shelves stacked with cups and plates. When the donors left, it all went back to the school.

In its response to Businessweek, WE said that no kitchen was constructed temporarily to show donors, though one was built and soon dismantled at the request of local community members, who wanted the space repurposed. It said, too, that it would have made no sense to slow down projects or redo tasks because “there is no shortage of good work to be done in Kenya.” It also said that it doesn’t require local villagers to wear traditional clothing for donors, that existing donor plaques are cemented into buildings, and that it didn’t swap them.

The Kielburgers’ greatest demonstration at Bogani may have come in March 2017, when Chip Wilson, the billionaire founder of Lululemon Athletica Inc., arrived. Wilson was seeking a candidate to take over Imagine 1 Day, a charity he and his wife, Shannon, had set up a decade earlier with a simple mandate: to help every Ethiopian child have access to education, free of foreign aid, by 2030. The organization had little of WE’s flash, but it had a reputation for being smoothly run by its Ethiopian project staff, extremely effective, and fastidiously transparent. It built schools in remote and sometimes restive areas, asking communities to come up with 10% of the cost to test their commitment to sustaining the school after Imagine 1 Day withdrew. “They were doing the real work,” says Mary Anna Noveck, a board member of Imagine 1 Day’s U.S. fundraising arm until it was dissolved in December 2019. “They were in the trenches.”

Marc was at Bogani for the Wilsons’ arrival, hoping a stay would convince Chip that WE was the one to take Imagine 1 Day to a new level. The visit was to be flawless, right down to the elder’s blessing, according to two former employees. The pitch apparently worked: In early May 2017, Wilson transferred Imagine 1 Day and C$10 million to WE. Within months, ME to WE expanded its voluntourism packages to Ethiopia, beckoning young travelers in a slick video “to change the world” while also climbing up the steps of 1,000-year-old churches, sipping local coffee, and tasting fermented flatbread. In Kilte Awlaelo, in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region, Imagine 1 Day purchased a 2-acre plot near one of its school projects, promising villagers a farm project and irrigation system in keeping with the grand vision the brothers had outlined to Wilson.

It wasn’t long, however, before the amount of money making its way to Imagine 1 Day’s operations in Ethiopia began to drop, a lot. The charity’s financial statements show that program spending there steadily fell from almost C$4 million in 2016, before the takeover, to C$1 million in fiscal 2019. (WE says it encountered a two-year delay in expected funding from a major sponsor.)

WE also started taking roughly C$15,000 of every C$50,000 in donations coming to Imagine 1 Day from one of its longtime partners in Ethiopia, Run for Water, according to the latter’s chair, Ken Mackenzie. He says WE called the money an “administrative cut” and only dropped the fee after Run for Water threatened to take its donations elsewhere. (WE says the administration rate was 10%.) Mackenzie, Noveck, and two other people with direct knowledge say that after the WE takeover, with Imagine 1 Day’s budget stretched, its country director, Seid Aman, had to let some staff go but tried to keep the problems under wraps to avoid jeopardizing relationships with other donors and local officials. “Chip got bamboozled,” says Noveck. “I think their sales and their marketing really dazzle a lot of people. … It wasn’t just Chip—it was a lot of people with deep pockets and star power.”

In Kilte Awlaelo, it took two years for construction to start on the irrigation project. Then in April, as the pandemic began to rage, the funding ran out, according to Negusa Tadesse, the local village chief. Work stopped, and a contractor abandoned the job and began trying to sell off materials to recover some of his investment.

In its response to Businessweek, WE said that it would be “inaccurate” to say employees were cut, and that the “total cost” of full-time staff didn’t decrease during its period of control. It also said it wasn’t informed that a contractor contended he hadn’t been paid in Kilte Awlaelo and disputes that funding ran out but referred questions to Imagine 1 Day. And it said that its partnership with the organization had recently ended and that it had returned the unspent portion of the C$10 million endowment to the Wilson family office to support Imagine 1 Day under Seid’s leadership. Seid didn’t respond to multiple requests to comment. Wilson declined to comment.

Back in Canada, Imagine 1 Day had also been pulled into a parallel business the brothers had been engaged in from an early age: real estate. Their schoolteacher parents, Fred and Theresa, were house flippers, moving the family into a new fixer-upper every year as the boys learned to paint, grout tile, and install sinks. According to a history posted online by WE, when Marc was a toddler, he’d help hang wallpaper; then, while he slept, the “wallpaper fairy” would come and fix his work.

The brothers never lost that fondness for property. Around 2004, they persuaded their parents to sell the family home and buy a three-story building in Toronto’s Cabbagetown neighborhood, which became the charity’s headquarters. Over the next five years, according to a 2010 Globe and Mail story, the charity, ME to WE, and another company linked to the Kielburgers collectively spent more than C$11 million on a dozen properties in Cabbagetown.

WE and WE affiliates next began snapping up buildings along Queen Street in the hardscrabble neighborhood of Moss Park. By 2017, a glass-walled, state-of-the-art headquarters—purchased, refurbished, and equipped by donors, including Microsoft Corp. and Siemens AG—sprouted on one street corner like a high-tech bubble in a sea of graffiti, needle drops, shelters, and struggling small businesses. As the charity moved to the area, it says, it sold its Cabbagetown properties, making a C$4.2 million profit.

The Kielburgers’ plan was to stitch the Moss Park properties together into a kind of incubator for youth activists and socially minded entrepreneurs—a “campus for good.” Imagine 1 Day was brought in to the spree, borrowing C$3 million from WE Charity to buy a former legal clinic, according to financial disclosures and property records. Today, the two-story building appears disused, with its windows and doors papered over and “No Trespassing” signs on display. (WE says Imagine 1 Day’s ownership was in “name only,” was designed to avoid a zoning bylaw problem, and was funded with proceeds from the sale of WE Charity properties in Cabbagetown.)

The brothers have long held that WE’s real estate portfolio provided long-term security for its charitable operations. As its property holdings grew in value, though, some questioned whether the focus on real estate was coming at the expense of overseas programming. Last fiscal year, the value of WE Charity’s land and buildings was C$44 million, against C$27 million spent on international programs. For comparison, the land and buildings held by World Vision Canada, another development-focused charity, were valued at C$19 million, against C$300 million in international programs. “Clearly,” says Mark Blumberg, a Toronto lawyer whose practice focuses on charities and nonprofits, “to conduct foreign activities at the scale that WE Charity was doing does not require that much real estate.” WE disputes this, noting that the majority of its programs are today domestic, and that its real estate is required to support them. It says it spent C$30.5 million on projects and education in Canada in 2018 vs. C$20.1 million internationally.

The C$44 million worth of property that WE Charity holds covers what it’s required to disclose as a registered nonprofit. It’s harder to find details about properties owned by private companies affiliated with WE. And it’s also not always clear how the ones that can be identified are related to the organization’s development mission. One such property, Toriana, a 4-acre beachfront haven that an agent’s brochure describes as “one of the largest and most luxurious private houses on the Kenya coast,” lies hundreds of miles from any WE development project. If anyone questioned its purpose, staff could recite from a prepared script that called it “a place to relax and reflect after an intense cultural immersion.” Internal records viewed by Bloomberg Businessweek show bookings were sparse in 2019. WE says that the property was bought with funds from ME to WE in 2010 “for the exclusive purpose of hosting ME to WE Trips to Kenya” and that revenue from guests staying there after volunteering stints at Maasai Mara “benefits the work of WE Charity.”

The WE organization’s use of private affiliates can also make it challenging to see how its money moves. Over the years it created enough of them that, in Canadian parliamentary testimony this summer, a longtime board member named Michelle Douglas said she didn’t know how many entities it had. The main private company, ME to WE, isn’t required to disclose its financials, but WE told Businessweek its auditors confirm that ME to WE has given the charity, on average, more than 90% of its profits over the past five years. It also noted that it was awarded a score of 96 out of 100 for accountability and transparency by Charity Navigator, which evaluated its U.S. arm.

Businessweek’s examination of WE Charity’s audited financial statements from 2014 to 2019 identified more than C$12.5 million in contributions from ME to WE. Over the same period, about C$9.5 million flowed back to ME to WE, as the charity purchased discounted goods and services. Bahen, of Charity Intelligence Canada, describes the latter flow of money as “backwash,” and Narinder Dhami, managing partner at social-impact investment firm Marigold Capital, characterizes flows of that magnitude as “highly irregular.” In its response to Businessweek, WE said ME to WE also provided in-kind support that directly offset the equivalent amount of expenses for WE Charity, and that kept the charity’s administrative costs below the industry average. Scott Baker, chief operating officer of WE Charity, said that under this arrangement, “the benefit is clearly going one way: the social enterprise exists to help the charity.”

During parliamentary testimony, Craig acknowledged building a “labyrinth” over 25 years, in part to comply with what he described as overly restrictive Canadian tax rules. He said the approach was also intended to ensure that each overseas jurisdiction had separately incorporated entities complying with local laws. (Matthew Literovich, a Toronto-based lawyer at Dentons, has written that while it’s standard for nonprofits to rely primarily on the combination of a foundation or holding company to accumulate donations and an operating company to deliver services, “more elaborate entities are not necessarily a sign of wrong-doing.”)

“Fundamentally, there are two overarching structures: WE Charity and ME to WE Social Enterprises,” Craig told lawmakers, adding, “we probably could find a streamlined system to do this.”

Throughout 2019, WE Charity still seemed ascendant. It could boast that it had provided 1 million people with clean water and helped educate 200,000 students. More than a million Canadian schoolchildren had attended WE Days, and ME to WE had sold 42,000 volunteer trips since 2005. WE Charity’s U.S. arm alone had raised $140 million from corporate donors in the five fiscal years leading up to that September, with $65 million coming from Allstate, KPMG, Microsoft, Unilever, and Walgreen. Both Kielburgers had been awarded the Order of Canada, one of the country’s highest civilian honors, and they jointly claimed at least 25 academic or honorary degrees and 10 books. A generation had grown up associating them with progressive Canadian values.

By the new year, the pandemic loomed. Within months, schools closed, travel halted, stadium-size rallies became impossible, and WE’s model began to suffer. In a roughly two-week period in March, it cut about 40% of its global staff. Then, in June, Trudeau’s government made the announcement that WE would be the lone administrator of the C$544 million student grant program. The charity would be paid as much as C$35 million, an amount roughly equivalent to a year of donations from corporate partners and foundations.

Accusations of favoritism erupted. The Kielburgers had long been clubby with Canada’s elite, and scores of current and former politicians, executives, and their families had made pilgrimages to WE’s overseas projects. Trudeau, his mother, his brother, and his wife had all participated in WE events, and Grégoire Trudeau also hosted a podcast for the charity. It emerged soon after the government’s announcement that the charity had previously paid the three Trudeau family members a total of C$427,000 in speaker fees and expenses since 2012.

Trudeau’s finance minister, Bill Morneau, was no less enmeshed with WE. In 2016 a book his daughter Clare had compiled from a pen-pal program involving refugees in Kenya was blurbed by Marc, which led to a speaking engagement at a WE Day in Ottawa. The next year, Clare and her mother, the French-fry heiress Nancy McCain, sojourned to Bogani, and the family visited ME to WE’s Minga Lodge in Ecuador. In April 2018, four months after the latter trip, McCain donated C$50,000 to WE Charity. The following summer, another daughter, Grace Acan, got a one-year contract to work in WE’s travel department. So close were Morneau’s ties with the Kielburgers that his office once described them as “besties.”

Critics of the Covid relief deal also noted that the entity set to run the program wasn’t even WE Charity, but rather the WE Charity Foundation—an entity whose purpose eluded WE directors in 2018 when it was set up to “hold real estate,” according to testimony from Douglas, the longtime board member. The Kielburgers later testified that they’d routed the arrangement through the foundation to protect the charity’s assets from potential liability.

Within eight days of Trudeau announcing that WE would run the program, the government and the charity dropped the agreement. Morneau, belatedly discovering that his family hadn’t paid for its trips to Kenya and Ecuador, reimbursed WE for C$41,366 toward the end of July. He resigned abruptly the following month amid a broader rift with Trudeau. The government said it hadn’t opened the deal to competitive bidding in the interest of getting the aid out speedily, but it acknowledged that neither Trudeau nor Morneau had recused themselves from the decision-making process. Canada’s ethics commissioner is conducting a conflict-of-interest investigation into both men—for Trudeau, the third such probe in as many years. Both have apologized for their lapses in judgment.

Compounding WE’s troubles, Jesse Brown, one of the lone journalists to scrutinize the charity before the furor, posted a copy of a report that a private investigator hired by WE’s defamation lawyer had compiled on him and his family after he published a critical series on his news site, Canadaland. (“WE Charity was not involved in the preparation of the document,” the nonprofit says.) The Canadian media also picked up on an Instagram post that Amanda Maitland, a former employee who’d traveled to WE-affiliated schools in Canada to give anti-racism talks, had made not long before Trudeau’s announcement. Defying a nondisclosure agreement, Maitland recounted having a speech about the personal injustices she’d suffered as a Black woman rewritten by White colleagues into a bland script about “cornrows” and “the Oscars.” “I was supposed to memorize this new speech and perform it,” she said in an interview. “I don’t know if they understood how oppressive that was.” By the time the media picked up her story, others were adding theirs, alleging an abusive and racist workplace culture at WE; 200 past and current employees ultimately signed a petition to demand that the Kielburgers personally apologize for the trauma caused by a “culture of fear, abuse of power, silencing tactics, and microaggressions.” In response, the brothers posted a letter apologizing to Maitland and said WE had started a “diversity and inclusion listening tour” to solicit feedback from current and former employees.

Sponsors such as Royal Bank of Canada, Virgin Atlantic Airways, and KPMG mutually agreed with WE to part ways. Then, in a televised interview in September, the brothers dropped a bombshell: They were shutting down WE Charity in Canada. In the hourlong interview, Marc’s eyes welled up as he spoke about the “political quagmire” bringing down a 25-year labor of love. Craig insisted WE is transparent. (“People say ‘complex entities.’ It’s actually not. There’s only two entities.”) And what would they do with their for-profit businesses? Undecided, the Kielburgers said.

WE Charity later wrote in a press release that there would be no more WE Days in Canada, no more WE Schools staff, and no more new WE Village school, water, or agriculture projects. The charity would also sell off an unspecified number of its Toronto properties to fund an endowment to sustain its flagship international projects. A report commissioned by a U.S. donor, the Stillman Family Foundation, said WE could expect to net as much as C$25 million from the sales.

And yet a comeback could still be in the works. WE is evaluating what to do in the U.K. and continues to operate in the U.S. Its American website bears no trace of its troubles back in Canada. The donations page will accept your gift for education in Ethiopia, prompting you to start with a one-time contribution of $75 and reminding you that WE Charity was ranked No. 1 by MoneySense in the international aid category.

In Kilte Awlaelo, in that country’s Tigray region, disappointment and confusion linger over the unfinished agricultural project. “The dream was big,” said Negusa, the village chief. “They gave us hope, but it was interrupted.” That was in September—before WE relinquished control of Imagine 1 Day, before Tigray was beset by civil war.

In the time since, the Stillman Family Foundation has taken out full-page ads in Canadian newspapers touting the results of two reports it commissioned that absolve WE Charity of any wrongdoing in the political scandal. It has set up a new website, Friends of WE Charity, inviting supporters to write in. One parent thanks the charity for her son’s trip to Nicaragua—for giving him an understanding of his privileges and an awareness of poverty. Another, a teacher, laments the loss of the WE Days whose performers had so inspired her students.

During their big TV interview, the brothers were asked: Was it fame—their own and the kind they attracted—that had brought about their fall? “We never considered ourselves celebrities. It’s not about us,” Marc replied. “It’s about the kids.” —With Simon Marks, Tom Contiliano, Stephan Kueffner, and Bibhudatta Pradhan

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.