NRA Goes International in Its Mission to Defend Guns

Gun control advocates have long said the NRA is more concerned with the needs of gunmakers than those of gun owners.

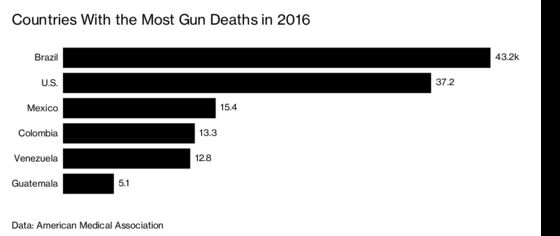

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When it comes to guns, Brazil and the U.S. have a few things in common. They rank first and second, respectively, in the number of citizens shot to death each year among the 195 countries that the American Medical Association tracks. The political dialogue in each country is dominated by a charismatic leader who says the answer to rampant violence is fewer gun laws and more guns. And both of those leaders—newly sworn-in President Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and U.S. President Donald Trump—are big fans of America’s National Rifle Association.

Bolsonaro made gun rights one of the main planks in his campaign platform, liberally salting his speeches with NRA talking points: “Guns are our guarantee of freedom,” he said during an event in the southern city of Curitiba last March. “The only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun,” his son Carlos posted on Facebook.

His victory shows that a core NRA principle—that armed citizens are safe citizens—is gaining political and popular traction far beyond America’s shores. Founded 148 years ago in New York by two Union Army vets to promote marksmanship, the group describes itself as the “oldest civil rights organization in America.” Its public events and messaging are often draped in the Stars and Stripes. Yet for all the patriotic symbolism, many of the forces shaping the NRA these days are distinctly non-American.

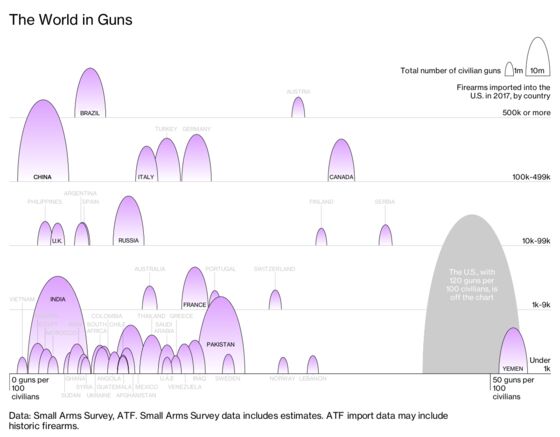

Gun control advocates have long said the NRA is more concerned with the needs of gunmakers than those of gun owners. (The NRA didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.) Lately, foreign backers—and foreign markets—have become much more important to the NRA. Imports have accounted for almost 1 in 3 U.S. gun sales in recent years, up from 1 in 5 less than two decades ago. Many foreign and multinational gun companies have opened manufacturing facilities in the U.S., taking advantage of the lucrative civilian market and relatively lax regulation, making them natural allies with the NRA.

U.S. gunmakers, in turn, have set their sights abroad. Exports of handguns, rifles, and shotguns for civilian use rose 64 percent in the six years through 2016, to 369,000 units, data compiled by Small Arms Analytics show.

As the gun industry has gone global, the NRA has taken positions that are hard to square with its all-American persona. In 2013 it stood with Iran, North Korea, and Syria in objecting to an arms trade treaty in the United Nations. (Republicans opposed ratification of the treaty in the U.S.) The following year it slammed the U.S. Treasury Department for including Kalashnikov Concern, maker of the iconic AK-47, among companies sanctioned in response to the Russian Federation’s aggression in Ukraine. The group acknowledged the hostilities but called the penalty a bid by U.S. gun control advocates for a backdoor assault weapons ban. A more global outlook also led to a major public-relations debacle, as some of the NRA’s top luminaries drew close to a young Russian gun rights activist, Maria Butina, who now admits she was trying to influence U.S. conservatives on the Kremlin’s behalf.

As gun culture has spread, advocates in countries as far-flung as Australia, Brazil, and Russia have looked to the NRA as their standard-bearer. It’s hard to see how this serves the group’s official mission as “a membership association that represents only individual citizens” of the U.S. But it’s easy to understand how it might serve global gun merchants.

● International gunmakers are falling in line

Just about anyone in any country in the world can join the NRA. Donations are a bit trickier, but as long as the organization doesn’t use them to influence U.S. elections, it’s free to accept them from abroad.

The NRA doesn’t break down its funding sources by country. A Bloomberg review of publicly available documents indicates that foreign gunmakers with big U.S. sales are big NRA contributors. Brazil’s Forjas Taurus, which generates 80 percent of its firearms revenue in the U.S., treats its U.S. gun buyers to an annual NRA membership, a $35 value. Data on imports indicate that Americans bought about 760,000 Taurus guns in 2017, the most recent year for which sales figures are available, though how many of those buyers became NRA members isn’t known.

Belgian arms manufacturer FN Herstal and its U.S. sales subsidiary, FNH USA LLC, donated $100,000 to $200,000 to the NRA in 2013, according to the Violence Policy Center, a nonprofit dedicated to reducing gun deaths. Ugo Gussalli Beretta, an executive of the Italian gunmaker Beretta, pledged $1 million to the NRA on behalf of the company in 2008, a gift that entitled him to membership in the Golden Ring of Freedom program, open to those who donate $1 million or more; Josh Dorsey, corporate vice president of Austria’s Glock, was inducted in 2017. A video Glock produced to celebrate the occasion shows images of Glock craftsmen building pistols and police officers carrying them, before cutting to NRA Executive Vice President Wayne LaPierre addressing a cheering crowd, while a narrator asks, “Why would you not give as much as you can to support the NRA?”

Differences of opinion between foreign gunmakers and the NRA have led to headlines in the past, notably in the 1990s, when Glock supported child-safety trigger locks in direct opposition to the association’s stance. Since then, foreign gunmakers have bitten off a sizable chunk of the U.S. market—thanks in part to the NRA’s growing influence.

In March 2000 the Clinton administration announced it had reached an “historic agreement” with Smith & Wesson, one of the nation’s oldest and most popular gunmakers. Under the terms of the deal, the manufacturer would add safety devices to handguns, develop smart guns that wouldn’t fire without the owner’s fingerprint, test firearms through the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, and sell guns only to authorized distributors. In return, the government agreed to settle some lawsuits pending against the company, though the settlement never materialized.

The NRA condemned Smith & Wesson’s decision, calling the company a “sellout.” Jeff Reh, general counsel to Beretta USA Corp., the U.S. arm of the Italian firearms maker, seized the moment. He told the New York Times: “I think that a fair number of Smith & Wesson customers will no longer want to purchase their products because of this agreement, and they will lose market share. A lot of gun owners will see this agreement as a betrayal of their Second Amendment rights and a capitulation to the Clinton administration gun control agenda.” He was right: Consumers revolted, and Smith & Wesson almost went out of business.

● Support at home can be volatile

The NRA’s stock may be rising abroad, but the organization is facing money problems at home. The gun rights group raised $312 million in 2017, the most recent year for which numbers are available—about a 15 percent drop from 2016, on the back of a 22 percent drop in member dues.

That dip in fundraising was reflected in how much the NRA and its PAC spent on 2018 campaigns. After laying out a record $55.6 million in the 2016 election, including $30 million to support Trump, it put only $10 million into supporting or opposing candidates in November’s midterms. NRA supporters give more when guns are under attack—meaning the revenue decline could be reversed if Democrats, emboldened by big wins in the midterms and empowered in the House of Representatives, try to do something about gun laws.

In the recent past, mass shootings and the backlash against guns that typically follows have been major boons to the NRA. The most significant was the December 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., which left 26 people dead, including 20 students under age 8. (The gunman also killed his mother.) The next year, NRA member dues reached a 10-year high of $175.6 million.

“Newtown all of a sudden became a huge issue,” says Richard Feldman, who’s lobbied on behalf of gun rights groups, including the NRA. In 2016, while Hillary Clinton was making gun control a central issue in her campaign, the organization raised a record $367 million, besting its previous high of $348 million in 2013.

With Republicans in charge of Congress and the White House, fundraising slowed on average. The exception was after the February 2018 school shooting in Parkland, Fla., which sparked nationwide demonstrations for gun safety laws. Some of the NRA’s longtime corporate partners severed their ties, and two weeks after the shooting, Trump said he’d “stand up” to the organization. ( He reversed himself a week later.) In the meantime, the NRA’s political action committee prospered: It took in a record $2.4 million the month after the massacre.

After the midterms, the financial tide shifted back in the group’s favor. In mid-December, Politico reported that House Democrats intend to come out of the gate strong pushing a gun control agenda. “I expect a surge in NRA membership,” Feldman says.

● The NRA’s message translates well abroad

The NRA has been such a financial and political success in the U.S. that gun rights organizations and politicians around the world look to it for inspiration. It’s a role the group embraces.

Three years ago, Australian Senator David Leyonhjelm appeared in an NRA video condemning his country’s restrictive gun laws. “We love the NRA here in Australia amongst us gun owners,” he said. “In fact, we rely on you guys to also help us hold the line.” In May 2017, members of the Sporting Shooters’ Association of Australia’s legislative action unit visited the NRA’s headquarters in Fairfax, Va., to talk strategy and “shared challenges.”

It’s likely to be a tough fight. Australians have mostly embraced gun control, dating to a 1996 mass shooting that left 35 people dead and 23 wounded. In response, the country established a firearms registry, banned automatic and semiautomatic weapons, and instituted a mandatory buyback program for certain types of guns. Shooting fatalities have plunged since, and there’s little popular support for revisiting the gun control debate.

Brazil is a different story. When Bolsonaro and his son Eduardo, a legislator and campaign aide, traveled to the U.S. in 2017, shortly after a gunman opened fire on a country music festival in Las Vegas, Gun World of South Florida was one of their first stops, according to a video of the trip they shared. While there, they tried out an AK-47 and other assault weapons. Afterward, Eduardo, donning a “F--- ISIS” T-shirt, held up large-caliber shells for the camera and expressed dismay that they could “have a problem” if they tried to bring the ammunition into Brazil. His father campaigned on giving police greater latitude to use their weapons. In his Jan. 1 inauguration speech, Bolsonaro declared: “Good citizens deserve the means to defend themselves.”

● Russian influence goes both ways

On Dec. 13, almost five months after Butina was first arrested on charges of operating as an unregistered foreign agent, the Russian national pleaded guilty in U.S. federal court to having worked covertly on behalf of the Russian government to influence the 2016 U.S. election toward candidates who would favor President Vladimir Putin’s agenda. Her mission, according to an FBI affidavit, was to meet politically influential Americans by infiltrating a “gun rights organization.” That organization was the NRA.

Butina relocated to the U.S. on a student visa in 2016, but she was already well-known in the Russian gun community as the founder of the advocacy group Right to Bear Arms. “My work has been focused exclusively on the expansion of gun rights—very publicly,” she told Time magazine a year later. “I am deeply grateful for the friendship of the American NRA.”

In 2015 some prominent members of the NRA traveled to Moscow, a trip funded in part by Right to Bear Arms. Among them were Milwaukee Sheriff David Clarke Jr., a darling of the so-called alt-right conservative movement; NRA benefactors Arnold and Hilary Goldschlager; former NRA President and current board member David Keene; and Pete Brownell, then an NRA board member who would go on to become its president. At the time of the trip, he was building a Russian sales network for his family business, Brownells Inc., which bills itself as the world’s largest supplier of shooting accessories.

Brownell, whose father has called him “the political animal in our family,” first ran for a seat on the NRA board in 2010. In early 2015 he set about expanding his business in Europe and Russia by taking over a distribution network from another prominent NRA member, Larry Potterfield, founder of firearms retailer MidwayUSA Inc. in Columbia, Mo. A person familiar with Brownell’s company says he didn’t discuss his business interests with anyone under U.S. sanction.

In Russia later that year, Brownell and the other Americans were introduced to Kremlin and industry officials. These included Dmitry Rogozin, the deputy prime minister overseeing the country’s defense industry, who was under U.S. and European Union sanctions at the time. The group also visited Russian gun manufacturer Orsis. Clarke later posted a photo of himself posing with what he said was the company’s T-5000 M sniper rifle, which the U.S. military has identified as a particular threat and “one of the most capable bolt-action sniper rifles in the world.”

With Butina’s arrest this year came harsh scrutiny of the NRA’s interactions with her and her mentor, Alexander Torshin. A recently retired Russian central banker, Torshin is a “Life Member” of the NRA (as is Butina) who frequented its annual meetings and crossed paths with prominent Republicans, including Donald Trump Jr. Spanish authorities have accused Torshin of laundering money for the Russian mob, and in April he was added to the U.S. list of sanctioned Russian officials.

The FBI has also been investigating whether the NRA served as a conduit for Russian money entering U.S. politics, including Trump’s presidential campaign, McClatchy has reported. Democratic Senators Ron Wyden (Ore.), Richard Blumenthal (Conn.), Elizabeth Warren (Mass.), and Sheldon Whitehouse (R.I.) wrote to Brownell and the other participants in the 2015 Moscow trip asking who organized and paid for it, whether NRA leaders signed off on it, and what interactions each had with Butina, Torshin, and Rogozin. The delegates haven’t responded publicly, and the NRA has denied funneling Russian money to the Trump campaign, saying it received only $2,500 from donors with Russian addresses before the 2016 election.

The NRA provided some documents in response to the Democrats’ inquiry, according to Wyden’s office, but refused to provide financial records Wyden had previously requested. After Butina pleaded guilty, Wyden wrote on Twitter, “Americans need to know: Who at the NRA knew Butina’s agenda, and what did they get in return?” —With Paul M. Barrett, Olivia Carville, Alexander Sazonov, Rachel Gamarski, and Maria Luiza Rabello

Barrett is deputy director of the NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights. Michael R. Bloomberg, founder of Bloomberg News parent Bloomberg LP, is a donor to groups that support gun safety, including Everytown for Gun Safety.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Eric Gelman at egelman3@bloomberg.net, Jillian Goodman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.