A Growing Army of Hackers Helps Keep Kim Jong Un in Power

A Growing Army of Hackers Helps Keep Kim Jong Un in Power

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Kim Jong Un marked a decade as supreme leader of North Korea in December. Whether he can hold on to power for another 10 years may depend on state hackers, whose cybercrimes finance his nuclear arms program and prop up the economy.

According to the U.S. Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency, North Korea’s state-backed “malicious cyberactivities” target banks around the world, steal defense secrets, extort money through ransomware, hijack digitally mined currency, and launder ill-gotten gains through cryptocurrency exchanges. Kim’s regime has already taken in as much as $2.3 billion through cybercrimes and is geared to rake in even more, U.S. and United Nations investigators have said.

The cybercrimes have provided a lifeline for the struggling North Korean economy, which has been hobbled by sanctions. Kim has shown little interest in returning to negotiations that could lead to a lifting of sanctions if North Korea winds down its nuclear arms program.

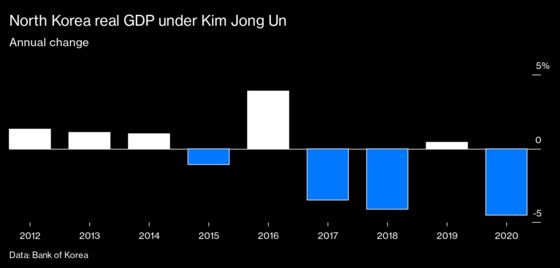

Money from cybercrimes represents about 8% of North Korea’s estimated economy in 2020, which is smaller than when Kim took power, according to the Bank of Korea in Seoul. (The bank for years has provided the best available accounting on the economic activity of the secretive state.) Kim’s decision to shut borders because of Covid-19 suspended the little legal trade North Korea had and helped send the economy into its biggest contraction in more than two decades.

Kim’s regime has two means of evading global sanctions, which were imposed to punish it for nuclear and ballistic missile tests. One is the ship-to-ship transfer of commodities such as coal: A North Korean vessel will shift its cargo to another vessel, or the other way around, and both vessels typically try to cloak their identity.

The other is the cyberarmy. Its documented cybercrimes include attempts to steal $2 billion from the Swift (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) system of financial transactions. North Korea has also illegally accessed military technology that could be used for financial gain, according to a UN Security Council panel charged with investigating sanctions-dodging by the government.

North Korea “is not afraid to be brazen and destructive in order to achieve the task at hand,” says Jenny Jun, a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative, who’s researched North Korea’s cyberoperations and cyberstrategies. “And this sets it apart from some of the other, more careful—and therefore more restrained—nation-state hackers.”

The government has deployed malware called AppleJeus that poses as a cryptocurrency trading platform to steal funds from people who try to use it. Since 2018 various versions of the malware have been used to target more than 30 countries. From 2019 to November 2020, AppleJeus hackers stole virtual assets valued at $316.4 million, according to UN and U.S. investigators. By comparison, North Korea’s coal exports are capped at $400 million a year under global sanctions.

Targets of the regime include central banks, the militaries of the world’s most powerful countries, and corner ATMs. It even tried to hack Pfizer Inc. for Covid vaccine data. South Korea said hacking attempts directed at it by its neighbor increased about 9% in the first half of 2021 from the second half of 2020.

The money North Korea gets from cybercrimes likely helps it to “fund government priorities, such as its nuclear and missile program,” the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence said in an unclassified report in 2021. The cyberprogram poses a growing threat, the report said, warning that the North Korean government probably has the expertise to cause “temporary, limited disruptions” of some critical infrastructure and business networks in the U.S.

Ji Seong-ho, who defected from North Korea to South Korea, where he’s now a member of the national assembly, says cyberactivity development under Kim is advancing rapidly. “The cybercapability in North Korea is bound to get more advanced, and the money it earns from hacking is likely to dramatically increase in the next decade,” says Ji, who sits on the assembly’s foreign affairs committee.

One of Kim’s top priorities when he took power was stepping up cyberwarfare capabilities. Operations under North Korea’s Reconnaissance General Bureau have grown significantly since then. At present it has more than 6,000 members in its cyberwarfare guidance unit, also known as Bureau 121, according to assessments in U.S. and South Korean unclassified defense reports.

The bureau’s four main divisions include Bluenoroff, with about 1,700 hackers, “whose mission is to conduct financial cybercrime by concentrating on long-term assessment and exploiting enemy network vulnerabilities,” said a 2020 U.S. Army report on North Korean military capabilities. The Andariel group has about 1,600 members, who look at computer networks and try to find vulnerabilities, according to the same report.

The U.S. government has been going after alleged North Korean agents, filing criminal complaints against people who, it says, illegally obtained confidential data from Sony Pictures Entertainment Inc. in 2014 and stole $81 million from Bangladesh’s central bank in 2016. (North Korea has denied any involvement in those hacks.) It also charged an American cryptocurrency expert, Virgil Griffith, with violating the International Emergency Economic Powers Act by offering North Korea advice on how to use cryptocurrency to launder money and evade sanctions; Griffith pleaded guilty in federal court in September.

Because North Korea’s hackers operate under the auspices of the isolated state and are rewarded at home for their thefts abroad, there is little that can realistically be done to punish those responsible. Counterstrikes on the country’s web infrastructure are limited because North Korea has few connected devices and its cellphone data network is mostly cut off from the rest of the world. “The fight against North Korea’s illicit activities is like a whack-a-mole game—cracking down will lead to displacement rather than cause [the regime] to stop or focus on legitimate economic activity,” the Atlantic Council’s Jun says.

Kim is using his sparse resources to invest in information technology training, sending experts abroad. He sees them as crucial for his survival, according to Kang Mi-jin, a North Korean defector who now runs a company in South Korea that watches the economy of her former home.

“The hackers consider what they are doing as being directly related to the fate of the Kim regime,” she says, “and what they are doing is likely to be one of [its] major sources of income.”

Read next: Cybercriminals Cash Out Ransoms at Moscow’s Tallest Tower

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.