The NFL’s Very Profitable Existential Crisis

The NFL’s Very Profitable Existential Crisis

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Consider the curious case of the National Football League: It’s the largest single entertainment property in the U.S., a $14 billion per year attention-sucking machine with a steady hold on the lives of tens of millions. And its future is now in widespread doubt.

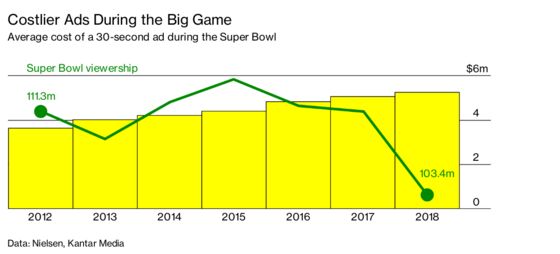

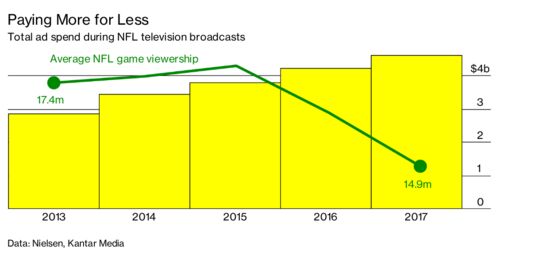

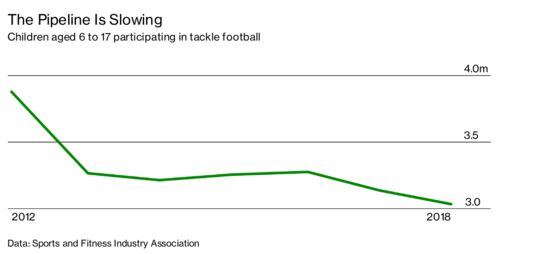

Ratings for regular-season games fell 17 percent over the past two years, according to Nielsen, and after one week of play in the new season, viewership has been flat. February marked the third-straight year of audience decline for the Super Bowl and the smallest audience since 2009. Youth participation in tackle football, meanwhile, has declined by nearly 22 percent since 2012 in the face of an emerging scientific consensus that the game destroys the brains of its players. Once a straightforward Sunday diversion, the NFL has become a daily exercise in cognitive dissonance for fans and a hotly contested front in a culture war that no longer leaves space for non-combatants.

To many outside observers, this looks like the end of an era. “The NFL probably peaked two years ago,” says Andrew Zimbalist, a professor of economics at Smith College who specializes in the business of sports. “It’s basically treading water.”

Yet even a middling franchise, the Carolina Panthers, sold in May for a league record $2.3 billion. Advertisers spent a record $4.6 billion for spots during NFL games last season, as well as an all-time high $5.24 million per 30 seconds of Super Bowl time. The reason is clear: In 2017, 37 of the top 50 broadcasts on U.S. television were NFL games, including four of the top five.

The Green Bay Packers, the only NFL team that shares financial statements with the public, has posted revenue increases for 15 straight seasons. Leaguewide revenue has grown more than 47 percent since 2012. Commissioner Roger Goodell’s official target is $25 billion in revenue by 2027, or roughly 6 percent annual growth.

“The business of the NFL is very strong and continues to get stronger,” says Marc Ganis, president of the consulting firm Sportscorp Ltd., and an unofficial surrogate for league owners. “It’s a great time to own an NFL franchise,” says Atlanta Falcons owner and Home Depot co-founder Arthur Blank.

The dominant sport in America has become Schrödinger’s league, both doomed and doing better than ever at the same time. This is a guide to how the NFL reached its remarkable moment of contradiction.

The NFL Experience space in New York’s Times Square is a year-round expo where fans paying $30 per head can experience a facsimile of the game, hitting blocking dummies and throwing balls to simulated receivers. Last month, a few dozen reporters gathered to listen to a facsimile of journalism, with upbeat conversations between NFL Network television hosts and league executives.

“Everyone loves to focus on the ratings, and everyone loves to focus on the NFL because it is the biggest ratings on television,” said Brian Rolapp, the league’s head of media. “But the reality is: Historically, the ratings of the NFL have always gone up, they’ve just never gone up in a straight line.” Anyway, Rolapp explained, falling ratings are the norm these days—and the NFL is holding up better than most.

It’s positive spin, and it happens to be true. The NBA, alone among the major U.S. leagues, has been able to buck this trend and add viewers for its national telecasts. But the NFL dwarfs the NBA. In 2017, four regular season NFL games drew more viewers than the most-watched NBA Finals game. “The NBA wishes it had the NFL’s ratings so that they could decline,” says Rich Greenfield, a media analyst at BTIG. During the first week of the new season, NFL games accounted for the five most-watched shows on TV.

Yet even team executives will admit that the NFL’s TV ratings make it the healthiest man at the hospice. “I don’t know that we’re ever going to be as popular as we were 20 years ago, or 10 years ago, just because of the way the world is,” says one team executive who asked to remain anonymous. “But I do think that, relative to the other options that are out there, we are still going to be dominant, and that will attract the revenue.”

The NFL makes unparalleled three-hour blocks of big-screen television with convenient gaps for ads at a time when consumers are gravitating toward shorter formats, smaller screens, and no interruptions. The league negotiated its last round of deals with CBS, ESPN, Fox, and NBC in 2011, at what now appears to be the peak of broadcast TV and the cable bundle. The NFL secured 66 percent price increases over its previous deals, with ESPN paying $1.9 billion annually for Monday Night Football and the others paying a combined $3.1 billion per year. ESPN’s deal expires in 2021, the others the following year.

“If I’m sitting at the NFL, I'm certainly getting nervous about the future of broadcast TV,” says Greenfield.

The rise of Netflix Inc. and other on-demand services has split in-home entertainment into things that people watch live and everything else. At the moment, there only two mainstays that demand to be seen as they happen: sports and President Donald Trump. “As the world fragments, we actually become more valuable because we are one of the only things left that can aggregate tens of millions of people in one place at one time,” says Rolapp.

When the NFL negotiated its last round of deals with the networks, it held aside mobile rights. For the last few seasons, Verizon Communications Inc. has paid hundreds of millions per year for the right to show games exclusively to its mobile customers. In December, the company re-upped at a steep increase. This time the NFL moved to make local games available on phones to anybody. “You will be able to open up your phone or your tablet no matter where you are, and whatever games are in that market on broadcast television you will get for free,” Rolapp told the crowd of reporters in August. “Whatever carrier, no cable subscription.”

The league has also been using its Thursday night slot to whet appetites in Silicon Valley. Twitter paid $10 million two years ago for the rights to stream 10 games simultaneously with the TV broadcast. Amazon.com Inc. paid $50 million for the same package a year later, and in April it re-upped for two more seasons at a reported $65 million per—all this on top of the $660 million that Fox is paying for the same games.

Amazon says more than 18 million total viewers in over 200 countries watched the NFL through its streaming service, “which is why we wanted to jump in and do it again,” says Jim DeLorenzo, head of sports for Amazon Prime Video.

The presumption is that when the league’s current broadcast deals expire, Amazon, Twitter Inc., Facebook Inc., Alphabet Inc’s Google, Apple Inc., or another deep-pocketed tech company will bid with the same fervor as their cable and television predecessors for an exclusive deal. “The tech giants are obviously preparing themselves to get ready for that,” says Daniel Cohen, a media rights consultant at Octagon sports agency.

While big-tech-to-the-rescue has become an article of faith around the NFL and other sports leagues, there’s reason to be skeptical. “There is an inevitable fragmentation that will hurt them,” says Zimbalist. “It means that they are not going to get the same rights fees.”

Recent precedent isn’t encouraging. When the English Premier League, the most popular soccer league in the world, auctioned its domestic TV rights earlier this year, Amazon took a slice of the pie and overall prices still fell by 10 percent from the league’s last deal three years ago.

“I think the NFL is 10 years away from an implosion,” Mark Cuban, owner of the NBA’s Dallas Mavericks, told reporters in 2014 in reference to the NFL’s expanded slate of Thursday night games. “I’m just telling you: Pigs get fat, hogs get slaughtered. And they’re getting hoggy.” Yet even Cuban, with his apocalyptic prediction, now foresees a bidding war between traditional carriers and streaming companies that will drive NFL rights fees up “significantly.”

Broadcasters have two obvious ways to make money from NFL games: selling ads and charging carriage fees to cable companies. For tech companies, the way to make money on sports is less clear. “It’s going be all about the trickle-down effect,” says Cohen. Maybe Amazon can use the NFL to get Prime subscribers to buy more groceries. Maybe someone from Silicon Valley will buy Ticketmaster or Fanatics and use football games as a platform to sell tickets and jerseys.

The NFL isn’t worried. “The fundamental rule in media is money always follows consumption,” says Rolapp. “If you have the consumption, figuring out how to make money off it is not the hard part.”

The league is also counting on the spread of legal sports betting. In May, the U.S. Supreme Court repealed the federal law that had barred the practice in most of the country. All the major U.S. leagues fought against this outcome in courts for years out of fear that match-fixing would tarnish the product. Now the NFL is salivating over the money that will flow as more states adopt legal betting.

The American Gaming Association, the primary lobby for the gambling industry, estimates that the NFL stands to gain $2.3 billion per year from legal sports betting, a factor of increased viewership, advertising, and rights deals for its live games and data. “It will not only create more fans, but it'll create fans that will pay even more attention to all of the NFL,” says Ganis.

During a break in the third quarter of last week’s season opener between the Atlanta Falcons and the Philadelphia Eagles on NBC, Nike Inc. bought 90 seconds to air what was, on its face, a familiar exhortation to dream big. It was also universally understood as a thumb in the eye of the NFL, delivered by one of its biggest sponsors.

Colin Kaepernick, the former San Francisco 49ers quarterback now famous for taking a knee during the national anthem in protest of police brutality and racial injustice, narrated the ad: “Believe in something,” he urged in the tagline. “Even if it means sacrificing everything.”

Kaepernick became a free agent last spring and remains unsigned as a parade of mediocre quarterbacks has come and gone. A few days before this season began, Nike announced that Kaepernick would be the face of its 30th anniversary “Just Do It” campaign. The ad—and the furor that followed—became the latest occasions for the political controversy that now follows the NFL at every step. Bashing the league has become a sport unto itself, with Commissioner Goodell and owners caught between those who see them as hopelessly old-fashioned and those who see them as not nearly old-fashioned enough.

Trump is quarterbacking for the revanchists. “Wow, NFL first game ratings are way down over an already really bad last year comparison,” the president tweeted after the game. “If the players stood proudly for our Flag and Anthem, and it is all shown on broadcast, maybe ratings could come back? Otherwise worse!”

Trump first decided to make the NFL into a hobbyhorse last fall at a rally in Huntsville, Ala. The league, he told the crowd, had gone soft. Players, he said, want to hit each other hard, and by not letting them, the league was “ruining the game.”

“But you know what’s hurting the game more than that?” he continued, the crowd booing and cheering on cue. “When people like yourselves turn on television and you see those people taking the knee when they are playing our great national anthem.”

It proved to be persuasive rhetoric. Earlier this year, when the public opinion research firm Morning Consult asked Americans how they viewed nearly 2,000 brands, the NFL tied for sixth place for most polarizing, alongside MSNBC. Only Trump Hotels, CNN, Fox News, NBC News, and the New York Times showed a wider division of esteem between Republicans and Democrats. In one of the more unpredictable twists of the culture wars, professional football now belongs to the liberal tribe.

The NFL has been less than resolute in dealing with the controversy. For a brief moment last fall, the league was able to co-opt Kaepernick’s original protest into a gesture of solidarity between owners and players. The weekend of Trump’s Huntsville speech, Jacksonville Jaguars owner Shahid Khan locked arms with his players before a game. Other owners and players repeated the gesture and a growing number of players knelt or sat during the anthem. Before the Monday Night game, Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones knelt and locked arms with players before the anthem but then stood for it.

By May, however, the political backlash prompted owners to unanimously approve a policy requiring players to either stand during the anthem or stay in the locker room. Then, after further backlash, the league suspended its new rule. “Basically, the NFL policy has been to kneel for Donald Trump,” says Zimbalist. “And it’s a stupid policy. It makes no sense.”

Yet there’s little sign that any of this is hurting business. In accidental way, it appears to have helped.

Last November, John Schnatter, better known as Papa John of the namesake pizza chain, blamed the NFL for his company’s declining sales. As the chain’s chief executive officer at the time, Schnatter was spending roughly $40 million annually on an official sponsorship deal with the league, plus advertising to go with it, and he didn’t approve of the league’s handling of the anthem controversy. “The NFL has hurt us by not resolving the current debacle to the players’ and owners’ satisfaction,” Schnatter said.

Three months later, after sales continued to flag, Papa John’s International Inc. announced it had abandoned its deal with the league. The same sponsorship slot was picked up by Pizza Hut the following day for more than Papa John’s had been spending. By then, Schnatter was no longer CEO; He later lost his seat as chairman of the board after using the n-word on a company conference call.

“I think the pizza category was open for about 32 seconds,” Maryann Turcke, the league’s chief operating officer, crowed to reporters in August. While sponsors were calling to ask some hard questions, she said, they weren’t letting Trump keep them away.

Other new sponsors are also showing up with piles of money. Sleep Number became the league’s first official mattress supplier earlier this year. And Nike, six months before its pot-stirring Kaepernick campaign, extended its deal to provide official jerseys until 2028.

Early in August, during an otherwise unremarkable day of training camp for the Minnesota Vikings, a safety for the team put on a black baseball cap with a message across the front: “Make football violent again.” Andrew Sendejo, who plays one of the game’s most violent positions with exceptional violence, was protesting a new NFL rule that bans players from initiating contact with their helmets. When asked what he thought of the new rule, Sendejo replied, “I don’t.”

Andrew Sendejo possibly sending a message to the NFL with his hat. Said he has been wearing for a while but that it still applies. #VikingsCamp pic.twitter.com/Q1aYwURvZx

â Tanner Peterson (@24tanner) August 3, 2018

Until two years ago, the NFL officially denied any link between football and increased risk of degenerative brain disease. That changed when Jeff Miller, the league’s senior vice president for health and safety, told members of Congress that there is “certainly” a link between the sport and diseases such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which has been found in the brains of more than 100 former NFL players and is linked to mood swings, depression, impulsiveness, memory loss, and in a handful of cases, suicide. “I think the broader point, and the one that your question gets to, is what that necessarily means—and where do we go from here with that information,” Miller said in response to a question from a congresswoman.

The question now is whether football can be played safely and still be football. In the short run, the NFL has to worry about ruining the fun for the group of people, including Trump, who see football as a vital tool in forging American manhood. As far as they’re concerned, any effort to subtract violence from the game and improve safety is a threat to the country.

“If we lose football, we lose a lot in America. I don’t know if America can survive,” David Baker, president of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, said in January. A few months later, North Carolina’s head football coach Larry Fedora echoed his sentiments: “I fear that the game will be pushed so far from what we know that we won’t recognize it 10 years from now. And if it does, our country will go down, too.”

In the long run, though, the NFL also has to worry that the widespread, lasting damage to players will alienate fans. “The CTE issue is the biggest challenge facing the NFL,” says Chris Nowinski, a former Harvard University football player and professional wrestler who started the Concussion Legacy Foundation. “If they don’t change—and change soon—their legends will keep being diagnosed with the disease and it will turn people off.”

At the moment, CTE can only be diagnosed post-mortem, by slicing into brain tissue. Researchers at Boston University, working with brains donated by families, have found that at least 10 percent of deceased NFL players suffered from the disease. Once scientists find a way to diagnose CTE in the living, which researchers expect to have in fewer than five years, Nowinski believes that this number is bound to double or triple: “If some day you knew that half the players you are watching on the field already have this disease, would you be comfortable watching?”

This year the Concussion Legacy Foundation launched a campaign called “Flag Football Under 14,” based on the research that shows one of the biggest predictors of CTE is the number of years spent playing tackle football. Parents, by the looks of it, were already getting the message. Since 2012, according to annual data compiled by the Sports & Fitness Industry Association (SFIA), the number of children aged 6 to 17 playing tackle football dropped 22 percent, to just above 3 million. In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics this year, researchers found that the fall in participation coincides closely with the rise of media coverage of football’s links to traumatic brain injuries.

The attention to brain injury risks turning football playing into a regional pursuit. In New England, according to SFIA data, the number of players has decreased by 61 percent in the past decade.

Bob Broderick, co-founder of football pad company Xtech, says he has spoken to nearly 2,000 high schools in the past few years and the appetite for youth football remains undiminished in Texas and the rest of the Southeast. “Whether you want to call it a religion, culture, or way of life, that’s the way it is down there,” he says. His most common problem is parents who want pads in smaller sizes for younger kids. “I bet you, in the last month, I’ve turned away 300 kids because we don’t make a product that’s small enough.”

It’s not clear that youth football’s shrinking footprint matters much for the health of the NFL. “The vast majority of people who watch the NFL have never played tackle football in their lives,” says Ganis. As long as elite players keep coming through the college ranks, he says, the league will be fine. And if the next generation’s Tom Brady opts to play baseball, who’s going to notice?

“The reality is that football is such a fun game for fans and a good game for TV,” says Nowinski, the anti-concussion activist, “that even if the quality was slightly worse, it would still be a massively popular enterprise.”

Jerry Richardson, the 82-year-old fast-food magnate who had owned the Carolina Panthers for a quarter century, was forced to sell the team earlier this year following revelations that he had sexually harassed team employees. Richardson, who had been one of the NFL’s most powerful owners, was a prime example of the old boys’ club that runs the league. The ownership ranks include the CEO of a truck-stop chain that has been accused by federal prosecutors of cheating customers out of fuel rebates, the scion of a heating and air conditioning fortune with a DUI on his record, and several heirs to oil money. They are not necessarily the group one would choose to steer an enterprise into the chaotic future of sports and entertainment in America.

But there’s no shortage of new economy billionaires lining up to replace them, just as hedge fund chief David Tepper did with his $2.3 billion takeover the Panthers. The fury that now surrounds these men, and they are mostly men, is both a test of their power and a testament to it. As much as they might long for the days before CTE was a household term, Kaepernick was a civil rights hero, and Trump was president, they’re happy to be in the middle of the conversation. It’s proof that they still matter.

The league office has a mantra for the mix of anxiety and defiance that now pervades those who control the sport. Goodell uses it often, and Rolapp repeated it in August just before the new season began: “Only the paranoid survive.”

--With assistance from Craig Giammona and Scott Soshnick.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Aaron Rutkoff at arutkoff@bloomberg.net, Janet Paskin

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.