New Obstacles Arise for the New Nafta

New Obstacles Arise for the New Nafta

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- President Donald Trump was quick to proclaim victory in September with the sealing of a deal to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement. He claimed the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, as the new deal is known, offered proof that his pugnacious approach toward tariffs and trade could deliver. If all goes as planned, U.S. officials will join their Canadian and Mexican counterparts in Buenos Aires on Nov. 30 for a ceremonial signing. But that marks just one step on the new Nafta’s winding road toward becoming a business reality.

The U.S. president’s next challenge is to get the deal through Congress. Democrats, the incoming majority in the House of Representatives, say they’re ready to deny Trump the easy win he craves. Richard Neal, the Massachusetts congressman set to take over as chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, says he and his fellow Democrats have concerns over a new pact he calls not “properly fashioned yet.” Bill Pascrell, the outspoken New Jersey Democrat and longtime Nafta skeptic vying to chair the Ways and Means trade subcommittee, is blunter still. “The deal was not a deal,” he says. “You’re going to see a lot of changes.”

In the U.S., trade deals are subject to a procedure known as Trade Promotion Authority. TPA guidelines allow these deals to avoid endless amendments and limit Congress to an up-or-down vote. There are often lengthy negotiations between the legislative and executive branches before a bill gets to the floor, however. A congressional vote on legislation implementing the USMCA’s provisions isn’t expected until next fall.

Trump says the new Nafta, which looks a lot like the old Nafta, fixes many problems of the 1994 pact he once labeled “a disaster.” The USMCA’s main feature is a stricter set of rules on the manufacturing of automobile parts, which require that 40 percent of a vehicle’s value come from high-wage plants in the U.S. and Canada. Critics argue that the regulations will only raise costs and hurt the North American auto industry’s international competitiveness.

Democrats’ concerns are centered on the new agreement’s labor provisions—which require Mexico to do more to allow the creation of independent unions—and how they’ll be enforced. The AFL-CIO and other labor groups argue that Mexico wouldn’t face any real economic costs if it violates the measures included in the deal.

Neal and others have so far stopped short of saying they want to reopen negotiations among the three signatories. Pascrell concedes that many changes he’d like to see can be addressed in implementing legislation. Robert Lighthizer, Trump’s trade czar and the lead negotiator of the USMCA, plans to meet with House Democrats before the end of November, Neal says, to discuss their concerns and develop a possible timeline for votes.

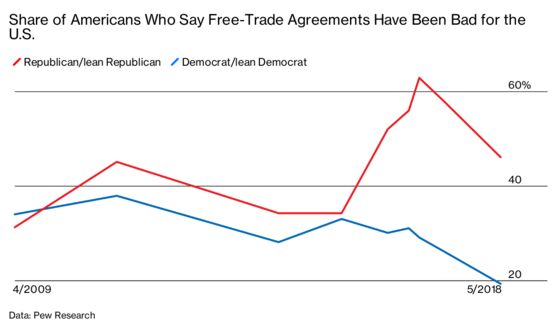

Many who object are trying to reclaim political ground from Republicans, who’ve co-opted labor issues from Democrats, says Edward Alden, a veteran watcher of Washington trade politics now at the Council on Foreign Relations. Lighthizer himself is a Reagan administration alumnus but has long challenged the Republican pro-free-trade consensus. During the USMCA negotiations he regularly solicited advice and support from Democratic trade skeptics such as Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown, even as he held many Republicans at arm’s length. Democrats now feel the need to look tougher on trade than Trump, Alden says, adding, “There’s a lot of Democrats who hate that he took that away from them.”

Although both U.S. neighbors remain frustrated with Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs, ratification may be more straightforward in Canada and Mexico. The new deal has the backing of Mexico’s incoming president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who takes office the day after the scheduled signing and will have to shepherd it through the country’s Senate.

William Reinsch, a veteran of congressional trade politics now at the Center for Strategic & International Studies, is worried Democrats may overplay their hand if they hold the USMCA hostage to secure concessions on immigration or other issues. Such a move could lead Trump to do what he’s long threatened and pull the U.S. out of Nafta, which in turn would cause angst aplenty for the businesses and farmers that rely on the deal.

While most analysts expect Republicans to fall in line, some conservatives have their own demands. Almost 50 Republican members of Congress recently wrote to Trump demanding he renegotiate the USMCA to remove language requiring policies to prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation or identity. On Nov. 21, Republican senators sent another letter asking the president to push the agreement through Congress before the end of this year to avoid the Democratic objections, though that option was quickly shut down by senior Republicans. “Congressional consideration of USMCA this year is not realistic, but I look forward to continuing consultations with the Trump administration,” Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch said in reaction to the letter.

The road ahead is likely to feature “a lot of drama” and “a lot of acrimony,” says Reinsch. “It’s an old game.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.