The Next Streaming Showdown Is a Race for Eyeballs in Southeast Asia

Tencent and IQiyi, are expanding across Southeast Asia, setting up the first real battle between Chinese streaming giants

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- As streaming has transformed much of the world’s media landscape, most of the competition has been between Western outfits vying to conquer the big video markets of the U.S., Europe, Latin America, and India. But now two of China’s largest online video companies, Tencent and IQiyi, are expanding across much of Southeast Asia, setting up the first real battle between Chinese streaming giants and their Western counterparts, Netflix and Disney.

In early June, IQiyi Inc., in which Baidu Inc. owns a controlling stake, hired away Kuek Yu-Chuang, Netflix’s main liaison to governments in Southeast Asia. A couple of weeks later, Tencent Holdings Ltd. acquired IFlix Ltd., a video service in the region. Both companies have recently ramped up efforts to produce and license local content and are looking to add staff in markets including Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

For both Tencent Video and IQiyi, the growing investment in Southeast Asia marks the companies’ most significant expansion outside China. Neither Netflix Inc. nor Disney+ operates there because of the country’s strict rules governing foreign ownership of media. So Southeast Asia will be the first real battleground in the growing Sino-U.S. tug of war over who controls global storytelling.

Tencent declined to comment for this story, but it said its acquisition of IFlix is part of its plan to expand WeTV, its international streaming service, across Southeast Asia. In a statement, IQiyi noted it was committed “to serving users of different markets.”

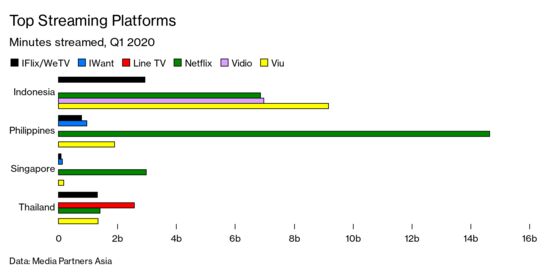

The Chinese streaming services are entering the fray before any company has established a dominant position in the region. Netflix, the leading streaming service globally, has yet to surpass 1 million subscribers in any country in Southeast Asia, according to consultant Media Partners Asia. Walt Disney Co.—which is Netflix’s biggest competitor in the U.S.—is planning to roll out Disney+ in Southeast Asia before the end of the year, according to a person familiar with the matter. “The Chinese companies are seeing an opening,” says Vivek Couto, who runs Media Partners Asia. “It’s neutral territory.”

Still, Southeast Asia presents a challenge for any global entertainment company. Outside a couple of pockets of affluence such as Singapore, most people in the region earn an average of less than $10,000 a year. And Indonesia, the area’s most populous nation, is home to hundreds of different languages and is one of several countries where the government imposes strict censorship rules. Before Kuek left Netflix, his primary focus was helping the streaming giant navigate such diplomatic challenges. He will serve a similar role at IQiyi, which first expanded overseas in June 2019.

The difficulty is evident in the story of IFlix. In 2015 entrepreneurs Mark Britt and Patrick Grove formed the service offering second-run Hollywood movies and local programs for about $3 a month, a fraction of the price of Netflix. They thought the price—and regional know-how—would win them customers while Netflix struggled.

In the years that followed, as Netflix attempted to expand in Southeast Asia, it ran into many of the problems that the IFlix co-founders had anticipated. Netflix was considered too expensive for many potential customers in the region, didn’t offer subtitles in many of the local languages, and wasn’t producing a lot of original programs for the area. The company also failed to strike a deal with Telkomsel, the largest telecommunications company in Indonesia. As a result, for the last four years, millions of people have had to skirt local restrictions by using virtual private networks to access Netflix. (The two sides just reached an agreement this year.) By contrast, IFlix has a deal with Telkomsel that allows locals to watch it legally.

Even so, IFlix failed to get much traction. In a region where traditional pay-TV services cost next to nothing and YouTube is ubiquitous, persuading people to pay for a streaming video service is a challenge, even at a low price. IFlix’s acquisition by Tencent “is not really a deal,” says Couto. “It’s a distressed-asset sale.”

There are signs the market for streaming services may be improving. Viu, owned by Hong Kong telecommunications giant PCCW Ltd., has had some success with a hybrid model, offering some programming for free on an advertising-supported service but charging customers who want a full range of shows and no ads.

Viu first gained a following by licensing shows from South Korea, which are popular across all of Asia. Subscriptions are growing 50% to 60% a year in most of its markets and account for half the company’s sales, according to Janice Lee, Viu’s chief executive officer. In Indonesia, people are spending more time watching Viu than Netflix or IFlix. Lee credited original series such as My Bubble Tea, a Thai drama, and an Indonesian version of the series Pretty Little Liars. “It’s doing phenomenally,” she says.

Recently, Netflix has started to attract more customers by selling cheaper, mobile-only plans and by producing a greater amount of local content. It now has about 800,000 subscribers in the Philippines, where it’s the clear market leader, and close to 600,000 customers in Thailand, where it’s second to Line TV, a local service. “Netflix has gone to the races, particularly in the last six months,” Couto says. “Consumption of Netflix in a lot of these markets is through the roof.”

Chinese technology is already part of everyday life in many Southeast Asian countries. Chinese manufacturers dominate the smartphone market, while TikTok, the short-form video app owned by the Chinese company ByteDance Ltd., is ubiquitous. But Chinese video services have yet to achieve similar popularity. Unlike TikTok, which relies solely on user-generated programming, IQiyi and Tencent Video offer catalogs of TV shows and movies. To challenge Netflix and Disney, which provide huge amounts of content from the U.S. and Europe, the Chinese companies will likely need to invest heavily in local programming and license top shows from Korea and China.

Most of the programming on IQiyi today is in Mandarin. The company is building an original production team in Thailand and has teamed with leading media and telecommunications companies in Malaysia and Myanmar. Viewers can now watch subtitled shows in English, Thai, Malay, Indonesian, and Vietnamese.

Historically, Chinese media companies haven’t looked to expand much internationally. Tencent, IQiyi, and a third service, Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.’s Youku, have focused on China, where each has spent heavily to compete for the next hit show. According to Reuters, Tencent has expressed interest in acquiring IQiyi, which lost $1.5 billion in 2019, to consolidate its control.

But in recent years, the idea of using entertainment to influence the outside world has grown more appealing to the Chinese government, analysts say. “China’s top leaders feel that their country can provide a model not only for economic development but also for political and cultural leadership,” according to a recent note from Gavekal Fathom China, a research company focused on Chinese industry. “That sense has strengthened during the Covid-19 pandemic.”

Read next: HBO Max Has Yet to Entice Key Group: People Who Already Have HBO

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.