A British Fund Star’s Fall Shows the Peril of Illiquid Holdings

A British Fund Star’s Fall Shows the Peril of Illiquid Holdings

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Neil Woodford is a famous fund manager in the United Kingdom. At a time when individual investors are pouring money into anonymously run index funds, there aren’t many of those left anywhere in the world. He now faces a crisis after he froze investors’ redemptions in his flagship U.K. fund, LF Woodford Equity Income, which has fallen about 22% in the past year. The freeze—a rare step for a fund aimed at ordinary investors—is supposed to buy him time to offload a bunch of “unquoted and less liquid” stocks in the fund’s portfolio, according to his firm’s website.

It’s a dramatic reversal of fortune for Woodford, a Warren Buffett devotee who built up a cult following by correctly calling major swings in technology, tobacco, and other stocks over decades. And fund investors everywhere, including in the U.S., can take away several important lessons from his flameout, financial advisers say. It points to the potential hazards of funds that invest in obscure, hard-to-sell assets—a rising concern that emerged again on June 19 when the fund researcher Morningstar raised questions about holdings in a fund managed by an affiliate of the French bank Natixis SA. And it shows the need for a healthy skepticism about celebrated money managers.

“Investors are prone to latching on to star managers, believing they’ve got the individual as the secret sauce, and that only they can potentially outperform the market,” says Todd Rosenbluth, director of exchange-traded fund research at CFRA Research. “People are fallible. Investments move in and out of favor. You should be buying a fund, not putting money to work for a specific manager.”

Woodford, through an external spokesman, declined to comment. The Oxford-based stockpicker has been managing money since at least 1987. He made his name at investment manager Invesco Perpetual, where he helped build up about £33 billion ($42 billion) in assets over almost 26 years and was among the biggest investors in U.K. stocks.

He was so well-regarded that on the day in 2013 that he announced he was moving on, Invesco shares slumped more than 7%. St. James’s Place, a U.K. wealth manager, took £3.7 billion of its clients’ money out of Invesco and parked it with Woodford just as his firm, Woodford Investment Management, was getting going. “We weren’t backing Woodford Investment Management, and we weren’t making a statement about Invesco,” St. James’s Place Chief Executive Officer David Bellamy said in 2016. “We were with Neil.” (St. James’s Place, whose investments weren’t in Equity Income, cut its relationship with Woodford after the freeze.)

In his first year on his own, Woodford’s Equity Income fund gained 16%, beating all 50 of its peers tracked by Bloomberg. He has maintained a bullish stance on Brexit’s impact on the British economy, a contrarian position that helped keep his venture in the spotlight even as returns faltered.

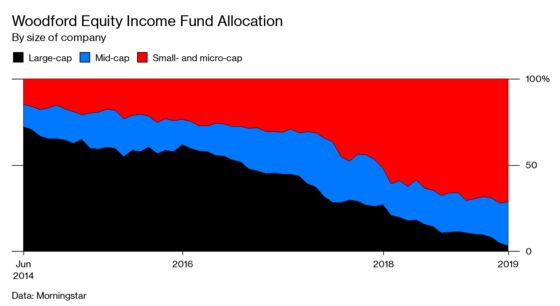

In the firm’s early days, Woodford focused on picking large, liquid stocks. Over time he moved toward smaller companies. What started as a gradual shift dramatically altered the profile of his fund. In the most recent portfolio disclosure before he froze assets, Woodford had allocated almost all of his fund’s assets to small and medium-size companies, according to Morningstar data. Some investments, including BenevolentAI and Industrial Heat, weren’t even listed on a major exchange.

“If you own an actively managed fund, you have to know what is held in the fund,” says Joshua Mungavin, a financial planner at Evensky & Katz/Foldes Financial Wealth Management in Coral Gables, Fla. “If the stocks owned by the fund are thinly traded or not traded on the public markets, then you know there is always a risk the fund could become as illiquid as its underlying assets.” In other words, you might find that you can’t take your money out when you want it.

The Equity Income fund was hit by declines in a number of its positions, including listed stocks such as the online real estate service Purplebricks Group Plc and consumer lender Provident Financial Plc. The poor performance led investors to pull money out, and its assets dropped by £560 million in May alone. The withdrawals began to put pressure on Woodford. To avoid becoming a forced seller of shares—and potentially having to accept fire-sale prices—the firm said at the start of June that the fund was freezing redemptions.

In the U.K., funds are allowed at most 10% of their assets in unlisted securities. According to the U.K.’s Financial Conduct Authority, the fund temporarily breached that limit twice in early 2018. Some companies in which Equity Income owned shares were later listed on the International Stock Exchange on the small island of Guernsey, helping the fund to stay within the rules. On June 18 the watchdog agency said it was investigating events that led to the freeze.

Woodford isn’t the first fund manager to run into liquidity problems. When the U.K. voted to leave the European Union in 2016, the country’s largest real estate funds froze almost £9.1 billion of assets as investors rushed to get their money out. M&G Investments, Aviva Investors, and Standard Life Investments all stopped withdrawals from the funds devoted to illiquid property assets. Those funds later reopened after markets calmed.

In the U.S., there’s Third Avenue Management, a mutual fund company founded by legendary value investor Marty Whitman. The firm managed as much as $26 billion in 2006, but it was hit hard in 2015, when its Focused Credit mutual fund imploded. As the crisis escalated, the fund, which invested in junk bonds, banned withdrawals. It was finally liquidated in 2018, with shareholders getting about 85% of the fund’s value at the time it shut its doors.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission says investments in illiquid products should be no more than 15% of a fund’s net assets. But concerns about funds investing in potentially hard-to-sell assets remain on both sides of the Atlantic. Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell and Bank of England Governor Mark Carney have noted in recent speeches that some investment funds hold illiquid debt securities. At the same time, fund companies are offering new products designed to make withdrawals harder, so that they can own more thinly traded assets (see the story here).

On June 19, Morningstar suspended its rating on H2O Asset Management’s Allegro fund because of concerns about rarely traded corporate bonds held by the European fund. The news caused a plunge in the shares of Natixis, which owns part of the money manager H2O. The bank said that the liquidity and performance of H2O funds had not been called into question. H2O said its funds had plenty of cash and that the allocation to non-rated bonds was below 10%.

What happened to Woodford is still extremely rare, especially for an equity manager. But even setting aside the withdrawal freeze, the fund’s poor performance will be a piece of evidence for those who argue that most investors are better off putting their money in a diversified index. And it shows that even investors who do want to try to beat the market would be wise to spread their bets. “Woodford’s story is simply one more painful reminder of the importance of diversifying—not only among different asset classes such as stocks and bonds but also among the different management firms who invest in them,” says Bruce Colin, an independent wealth manager based in Rancho Palos Verdes, Calif. “Individuals who choose to invest with a single fund manager, particularly one with a near celebrity-like following, should be particularly attentive to the risks they are courting.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.