Nashville Wants to Be the Next Austin, But Tennessee Won’t Make It Easy

Nashville Wants to Be the Next Austin, But Tennessee Won’t Make It Easy

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Three hours into an otherwise sleepy meeting of Tennessee’s Senate Judiciary Committee in late April, state Senator Paul Rose made his case for a bill that would allow faith-based adoption agencies to reject same-sex couples as potential parents.

“I realize there will be consequences for voting ‘yes,’ ” said Rose, who represents a suburban district northeast of Memphis. “But I also encourage you to think about the consequences of voting against the bill, as you face your God.”

His argument drew audible gasps from the gallery, but the legislation easily passed out of committee. Afterward a woman approached Rose to shake his hand and thank him for his service. A week later the bill’s sponsor punted the vote until the next legislative session, bowing to pressure from corporations that had lined up in opposition.

The increasingly powerful business community centered in Nashville views that bill and a handful of others like it as a threat to the city’s relatively new status as the state’s economic hot spot.

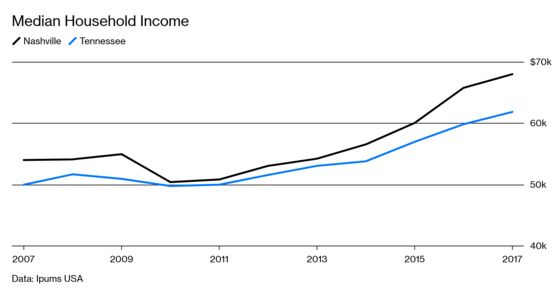

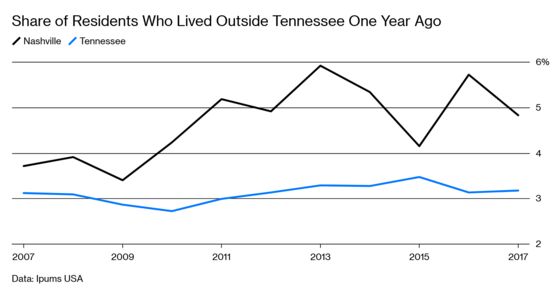

Led by the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce, the city has sought to position itself as more affordable but no less hip than Austin, Denver, or Portland, Ore. The campaign’s been working. Two years ago, Nashville passed Memphis to become the state’s biggest city. The population has grown more than 11 percent since 2010; over the same period, the city’s gross domestic product rose 64 percent, to $133 billion. Residents are also better off, with average household income hovering just under $56,000, up almost 40 percent from a decade ago.

Big, coastal corporations have noticed. A year ago, AllianceBernstein Holding LP announced plans to relocate its headquarters and 1,000 employees to a new tower in Nashville by 2020. Six months later, Amazon.com Inc. chose the city for an operations center, a development that will require two new buildings and create 5,000 jobs. “Our culture was a big feature of what we proposed,” says Ralph Schultz, chief executive officer of the Chamber of Commerce. “We’re open, we’re welcoming, we’re collaborative.”

The state’s newly elected legislators have a different vision for Tennessee, one that’s far more conservative than metro Nashville. In addition to the adoption bill, state legislators have proposed measures to defend public schools that want to restrict transgender students’ access to bathrooms and ban cities from favoring companies that promote diversity and protect LGBT workers when they award contracts. Both passed the state House but were also delayed until next year, again the result of corporate objections—and what Joe Woolley, CEO of the Nashville LGBT Chamber, described as impassioned behind-the-scenes lobbying. Republicans did score one victory: A bill to amend the law on indecent exposure to include incidents in restrooms and locker rooms—LGBT activists worry it’s a tacit endorsement of anti-transgender harassment—was signed into law on May 2.

Lots of blue cities have flourished in deeply conservative states, Austin first and foremost. But Nashville’s boom has come more recently, running parallel to a movement among large American companies to champion diversity and inclusion. While Tennessee has never been a liberal state, Nashville boosters are concerned that passing laws widely seen as anti-LGBT could slow the city’s momentum. “You could see businesses leave or decide not to invest further, and businesses that are considering a move to Tennessee making the decision to go elsewhere,” says Jeff Yarbro, a Democratic state senator who represents Nashville and opposes the bills. “I would like for us to signal that we’re a more welcoming state.”

Nashville’s corporate citizens present and future argue that the laws would be a drag on business. Amazon, AllianceBernstein, Bridgestone Americas, Dell, Salesforce.com, and Postmates signed an open letter urging legislators to vote down the proposals because “legislation that explicitly or implicitly allows discrimination against LGBT people and their families creates unnecessary liability for talent recruitment and retention, tourism, and corporate investment to the state.”

Meanwhile, Taylor Swift denounced the “slate of hate” in the state legislature. In April, as Nashville played host to its first National Football League draft, the Tennessee Titans NFL team issued a statement cautioning state lawmakers that the legislation would “impact our ability to secure events like the 2019 NFL Draft, major conventions, major athletic contests, and other events that benefit our local and state economy.”

In trying to fend off the legislation, business leaders have repeatedly invoked North Carolina, which suffered a broad-based boycott after passing a 2016 law to invalidate protections for LGBT workers in Charlotte and restrict bathroom use by transgender people. The NCAA said it would avoid the basketball-crazy state. PayPal Holdings Inc. scrapped plans to build an operations center in Charlotte, and German lender Deutsche Bank AG froze a $9 million plan to expand a software center employing hundreds of people in Cary, a small community outside Raleigh. The legislation has since been revoked.

The co-sponsors of the Tennessee bills declined repeated requests for comment. It’s possible that the boom in Nashville has created a sense of economic invincibility among the conservatives pushing the bills, says Chris Carpenter, who studies LGBT economic issues at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. “There are cranes on every street corner,” he says. “Nashville is the ‘it’ city. People don’t think about it ending or being slowed down by any kind of public policy.”

Carpenter says they may be right: There’s a lot to like about Nashville. Taxes are low. Housing is affordable. The city buzzes with the energy of its historic music scene and throngs of college students from a handful of universities. This wouldn’t be the first time companies have looked past conservative legislation in the state, including a 2016 law that allows therapists to refuse to treat patients based on religious objections.

Still, Butch Spyridon, president and CEO of the Nashville Convention & Visitors Corp., says he’s worried the anti-LGBT legislation could also discourage tourism, which contributed $6 billion to the economy last year. British Airways’ new nonstop London-to-Nashville flight is the carrier’s fastest-growing route in a decade. The state’s economic players say they’ll continue to do what they can. “We may be the hottest destination in the country,” Spyridon says. “Everybody’s enjoying the benefits of it. Why would you want to mess with that golden goose?”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Janet Paskin at jpaskin@bloomberg.net, Jillian Goodman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.