Covid Threatens Female Airline Pilots’ Progress

Covid Threatens Female Airline Pilots’ Progress

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Growing up in Amsterdam, Rachna Sharma Reiter felt like the exception. At age 7, she knew she wanted to be an airline pilot but never met any girls her age who shared that ambition. At flight school in the U.S., she was one of three women in a class of 150. After 16 years in the cockpit, she still finds herself being viewed as an anomaly. “It seems like things haven’t really changed,” says Reiter, who works for U.K. discount airline EasyJet Plc. “Whenever I go somewhere, they always tend to think I’m a flight attendant, even when I’m in my pilot’s uniform.”

The path to the flight deck has never been easy for women. Beyond the gender assumptions, there are the structural forces impeding progress. Male-dominated militaries have long fed pilots into airline cockpits, though vets have taken a smaller share of the openings in recent years. Once women do make it in, everything from a male-centered training environment to work rules concerning maternity can slow their advancement.

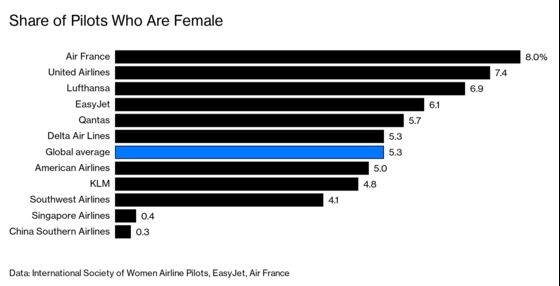

Still, there was reason for optimism before the pandemic hit. The share of female pilots rose to 5.3% worldwide this year, from 3% in 2016, according to the International Society of Women Airline Pilots in Las Vegas. Europe has led the way among the larger markets, along with a handful of countries like India, where the boom in air travel has attracted women to the well-paying profession.

EasyJet stepped up recruiting efforts several years ago under then-Chief Executive Officer Carolyn McCall. Deutsche Lufthansa AG increased female cockpit-crew representation to 7.1% by inviting more women to its in-house flight school. And fast-growing Wizz Air Holdings Plc announced an ambitious program to retrain flight attendants as pilots.

But with the coronavirus grounding lots of travel, that hard-won progress is at risk. Airlines are reeling, with more than 15,000 pilot jobs in Europe alone under threat of elimination, according to the European Cockpit Association. American Airlines Group Inc. and other U.S. carriers have started to lay off tens of thousands of employees. In Hong Kong, heavyweight Cathay Pacific Airways Ltd. says it will slash more than 5,000 jobs, including about 600 pilot slots. By yearend, job losses among all airlines globally, including flight attendants, ground staff, and others, could top 340,000, according to consulting firm Five Aero.

Female representation could slip toward 2016 levels, according to the women airline pilots group. By its estimate, the industry has lost almost 100 female pilots so far because of recent airline bankruptcies.

As they resize their staffs, most carriers are following a last-in, first-out formula when deciding whom to keep. This has put more recent arrivals, many of them women, at a disadvantage.

Decision-makers are “not thinking about last-in, first-out having an impact on female pilots,” says Jenny Body, a retired Airbus SE engineer who helped develop the fly-by-wire software used by modern aircraft and was the first woman to head the Royal Aeronautical Society. “If you look at the population in their 50s and 60s, it’s mainly men.”

The pipeline is also drying up. Lufthansa has temporarily stopped training new pilots. There’s no active initiative to attract more women because of the personnel surplus, a spokeswoman says. EasyJet, which reached its target of 20% female new-entrant pilots this year, says it’s paused recruiting and it’s not clear when it will begin taking on new staff again. Hungarian discounter Wizz still hopes its program, dubbed Cabin Crew to Captain, will help it boost the number of female pilots to 1,000 by 2027, from 50 now. But the initial class has been delayed until 2021. “We’re controlling our destiny,” says Tamara Vallois, Wizz’s head of recruitment. “Four to five years from now, that’s when aviation will hopefully bounce back, and by this time the profession will be in high demand again.”

At work, women pilots say their male colleagues generally show respect, but that’s not always true for passengers. Claire Ross, a 33-year-old pilot for German tour operator TUI AG, says she’s encountered comments such as “Are you old enough to fly a plane?” and “Are you sure you can park this thing?” Audrey Escoubet, 45, an Air France captain who’s been flying for two decades, says women are always proud to see a female pilot, but some men are “not so sympathetic.”

One of the biggest retention issues for women pilots is work schedules, according to a 2016 study in the International Journal of Aviation Management. Pilots are expected to spend as many as 15 nights a month away from home, which can cause issues for women flyers, who still often shoulder more caregiving duties at home. Many have been able to use flex time to help manage those family duties, but that also slows their progress toward promotions. (Globally, females make up only 1.4% of airline captains, according to the Las Vegas pilots group.)

Several women pilots who sought anonymity for fear of losing their jobs say they’re also penalized financially by such policies as mandatory safety-related groundings during pregnancy. This results in an effective pay cut of as much as one-third during the pregnancy, due to the loss of supplemental flying pay based on hours in the air.

And unlike other highly paid professions, European pilots often get only statutory maternity pay rather than a percentage of their salary during maternity leave. This can mean a 90% pay cut for those months. Some women pilots say colleagues have put off having children while they pay back loans taken to cover flight training, which can cost as much as $100,000.

While employment terms are often negotiated by worker councils, many lack female representation or haven’t prioritized negotiating for benefits that won’t affect 95% of their workforce. “The role of a pilot is man-shaped,” says Ross, who flies the Boeing 757 and 767 for TUI. “We need more females in these positions of responsibility to inspire and give confidence to others so that they can reach their full potential.”

Women pilots say they hope the pandemic crisis may ultimately help improve conditions in the cockpit by giving male colleagues a taste of what it’s like to be grounded for long periods of time, as women are during pregnancy and maternity leave. They hope this will lead to improved training and support for pilots returning after a break.

Reiter, the EasyJet pilot, has flown in Europe for the past 16 years and now lives in Berlin. She’s been furloughed since March. Her rank as first officer is below that of captain, putting the 42-year-old at a disadvantage based on seniority. She has a degree in aerospace engineering and two daughters, age 8 and 2½, and is pursuing an MBA online.

If she can’t return to the cockpit, she says, she would consider a ground-based role elsewhere in aerospace. Her 8-year-old plays soccer and wants to be an astronaut. “I would like every girl to think they can do whatever they want,” Reiter says. “I had no clue about what was male, what was female. I knew there were less girls flying, but just focused on what I wanted to do and went for it.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.