MLB Is Testing Ways to Fix Baseball’s Boredom Problem

MLB Is Testing Ways to Fix Baseball’s Boredom Problem

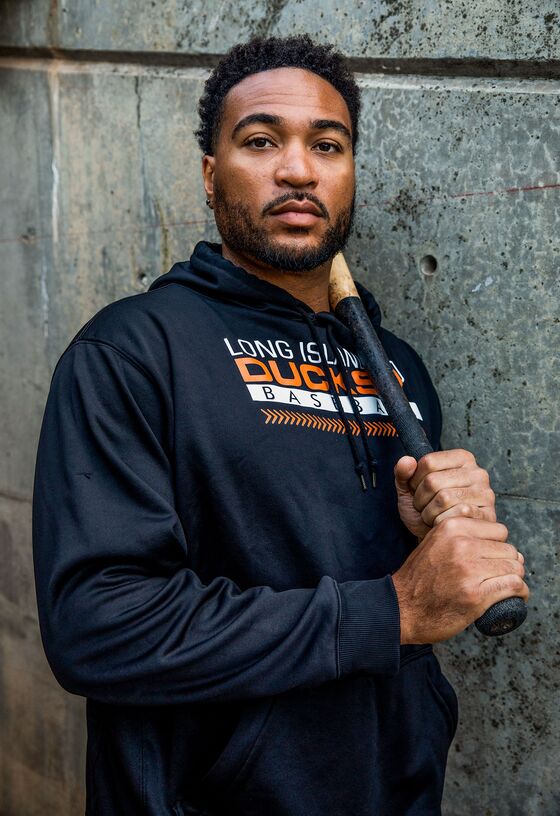

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Players and coaches in baseball’s Atlantic League had been dreading the change for more than a year. “I don’t understand why they’re doing it,” Danny Barnes, a relief pitcher for the Long Island Ducks, told me during batting practice a week before its debut at the beginning of August. “That’s a tough one,” said fellow reliever Joe Iorio. “We don’t want it to create injuries.” Ducks manager Wally Backman had heard these complaints and more. “The only reactions I have heard from the players are bad,” he said, sitting at his clubhouse desk at the Ducks home park in Central Islip, N.Y. Backman, who played for 14 seasons in the major leagues and won a World Series with the New York Mets, then mimed zipping his lips before he said too much.

When it happened, the big change was tough to spot from the stands. At an Aug. 11 game between the Ducks and the Southern Maryland Blue Crabs, I pointed it out to the father and son seated beside me: The groundskeepers had moved the pitching rubber back a foot farther from home plate. Since 1893, the white strip where the pitcher stands has been set at 60 feet, 6 inches, but now, in the Atlantic League, it was 61 feet, 6 inches. They were surprised to learn this, but the conversation quickly returned to how nice it was to go to a baseball game without spending hundreds of dollars.

The extended pitching rubber, hotly contested in clubhouses and barely noticeable to fans, is part of a wave of experimentation that Major League Baseball executives are hoping will drag their sport into the 21st century. Since 2019, MLB has been using the low-profile Atlantic League, whose players aren’t unionized and have little power to object, as a test lab for rules changes aimed at making games shorter and more exciting. These tweaks have included letting batters try to steal first base, making the bases bigger and easier to reach, strictly limiting visits to the mound by coaches, and using an Automated Ball-Strike system—robot umpires—to call pitches at the plate. MLB has already adopted some of the changes at the big-league level. If they work as intended, others will follow.

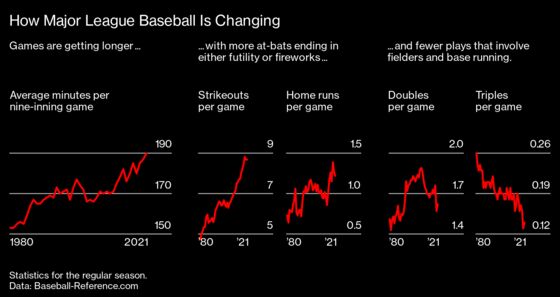

Baseball has a bloat problem. With every season, games take longer and less happens on the field. Over the past half-century, the average length of an MLB game has risen from about 2 1/2 hours to 3 hours and 11 minutes. The number of balls in play, meanwhile, has dwindled. Hits are near historic lows, strikeouts at historic highs. In 1980, roughly 1 in 8 trips to the plate ended in a strikeout. This season, the rate was twice that. This makes for long lulls in the action. According to the league, the time between batted balls has reached an average of nearly four minutes, up by almost a minute from two decades ago. It’s a worrisome trend for a sport that’s competing for attention with instantly refreshed social media feeds and eight-second viral videos.

You can blame Moneyball for the stagnation. The statsmongers who took over baseball’s front offices over the past 25 years taught teams that they could improve their odds of victory by removing the randomness of action on the field and keeping games between hitters and pitchers as much as possible. According to this school of thought, the most desirable outcomes of an at-bat are a home run, a walk, or—depending on whose side you’re on—a strikeout. But smarter baseball turns out to be less fun, a glorified game of catch punctuated by the occasional jog around the bases. Fielders stand around. Baserunners don’t slide, they stroll.

MLB knows viewers find this boring. Its own surveys show that fans most want to see triples and steals, both of which are about as uncommon as they’ve been in a generation. “What comes out of our research is that fans want more baseball in the baseball game,” says Morgan Sword, the league’s executive vice president of baseball operations. Sword, a 36-year-old former management consultant, is heading up its efforts to improve the quality of the product on the field. His working group includes former outfielder Raul Ibanez and former general managers Michael Hill and Theo Epstein, himself arguably the greatest practitioner of Moneyball.

Epstein, who relied on rigorous number-crunching to help turn the Boston Red Sox and Chicago Cubs into World Series champs, says he’s “well aware” of the irony that he’s now working to undo some of the sluggishness that his strategies wrought. But no, he says, he didn’t sign on as a consultant with MLB as some sort of penance. “Every writer wants to turn it into some biblical redemption story, where I have sold my soul for three World Series and ruined the game, and now my last great selfless act is going to be to reverse the course,” he says, “Not at all.” After years of unwavering focus on finding a competitive edge for his teams, he says, he’s excited to be looking at the game with a broader view.

In seeking to reverse-engineer the game to satisfy fans, baseball is taking a page from the NBA and NFL, both of which have adjusted their rulebooks over the last quarter-century to free up offensive play, leading to upswings in popularity. As caretaker of America’s pastime, MLB has tended toward a more conservative approach, but that has begun to change under Rob Manfred, who took over as its commissioner in 2015. In efforts to speed up game play and increase action, Manfred has limited mound visits and pitching changes and said he would consider banning infield players from shifting sides of the field. “I’m just thrilled that the commissioner is taking this seriously and being proactive and intentional about the product we put on the field,” says Epstein.

The experimentation comes at a delicate moment for the league. The pandemic forced MLB teams to take on a record $8 billion in collective debt, Manfred told the news site Sportico last year. MLB’s current collective bargaining agreement will expire in December, and relations with players are as strained as they have been since the most recent strike, in 1994. The devotion to data analysis that has led to the rise in strikeouts has caused teams to abandon their habit of paying for past performance, a shift that has alienated veteran players who count on free agency to make up for years of cost-controlled labor. MLB will need the players’ union’s support for any rule changes, which may require significant concessions.

“It’s going to be a little trickier to introduce this now, because of the acrimony,” says Andrew Zimbalist, an economist at Smith College and the author of Baseball and Billions: A Probing Look Inside the Business of Our National Pastime. “You have to convince players that a rising tide lifts all boats, that we can make this game more exciting and have more people in the stands and watching on television.”

Baseball is not about to die. The sports betting industry has been pouring money into the coffers of every league since the U.S. Supreme Court opened the way for its expansion beyond Las Vegas in 2018. The American League Wild Card game between the New York Yankees and Boston Red Sox on Oct. 5 drew 7.7 million viewers, the most for an MLB game on ESPN since 1998. And many fans have eagerly returned to stadium seats as pandemic restrictions have eased. Yet there remain underlying signs of decay. Average attendance has been falling since 2007. Youth participation has flatlined. MLB lacks the NBA’s global influence and the NFL’s TV ratings. If the league can’t solve its strikeout problem and find ways to get more action back in the game, it risks sliding from past-its-prime to irrelevant.

On June 19, for the first time in more than a year, the Long Island Ducks hosted a weekend game without capacity restrictions. The Atlantic League lost its 2020 season to the pandemic, and the Ducks began this year with crowds limited to 50%, or 3,000 fans. But on this Saturday evening, 5,131 people came through the gates to see the Ducks play the Lancaster Barnstormers. About half an hour before the first pitch, Ducks owner Frank Boulton peered through the blinds in his office to see rain pouring down. “Of course there’s weather,” said the 70-year-old former Smith Barney bond trader. “We have a fireworks show.”

Boulton founded the Atlantic League in 1998 after leaving Wall Street for a second career as a minor league baseball owner. He’d found himself frustrated by the MLB farm system’s restrictions on who could put a team where. After the Mets blocked his attempt to relocate the double-A Yankees affiliate he owned in Albany to his native Long Island, Boulton decided to start his own league instead. The idea was to match towns that were excluded from hosting minor league teams because of MLB territorial rights with players who had fallen out of the big-league farm system and were looking for a way back in.

At an average age of 27, the Atlantic League’s players are the oldest and most experienced in independent baseball. Sixty percent of those on this year’s opening day rosters had at least some major league experience. Ducks outfielder Daniel Fields, for instance, was drafted by the Detroit Tigers in 2009, spent six seasons working his way through the minors, and played in just one major league game, in 2015. Now 30, he’s been scrapping in the Atlantic League, where the maximum salary is $3,000 a month, for four seasons. Fields makes an excellent guinea pig for MLB. He plays the game at something very close to the major league level, but he’s not a prospect whose development a big-league club is trying to protect.

MLB first approached the Atlantic League about becoming a petri dish at baseball’s winter meetings in Las Vegas in 2018. Sword and some of his colleagues presented the idea to Rick White, a former MLB marketing executive who is now president of the Atlantic League. White loved it, but he wasn’t sure if the league owners would. Boulton, among others, was initially hesitant. “I don’t want to make this silly,” he says, sitting at his office desk with bobbleheads lining the shelf behind him. “I’m really a baseball purist, too.” But after MLB assured them it wouldn’t ask the Atlantic League to try anything it wasn’t seriously considering for its own clubs, he and the other owners decided to go for it. In February 2019, the two leagues announced a three-year deal, beginning that spring, that would allow MLB to test rule changes, including robot umps. In return, the Atlantic League would get a steady stream of detailed data about all its players—and the attention of the national press.

As part of the deal, MLB installed a ball-tracking device called a Trackman at every Atlantic League field. Roughly the size of a fat laptop, a Trackman can be found hanging in the rafters at 400 ballparks around the world, from the Dominican Republic to Japan. Each houses a doppler radar and two cameras that track the path of every pitch and hit, spitting out data on velocity, spin rates, release points, and launch angles. The eponymous Danish company behind the technology first developed it to track golf balls. It’s been selling the baseball rig for about a decade. For an annual licensing fee of “about the cost of a decent car,” says Hans Deutmeyer, who runs the baseball business, Trackman will install its hardware and supply the data stream, as well as a gameday employee to tag the information, matching hits and pitches with their corresponding players.

At the Ducks game in June, which got underway after a half-hour rain delay, most fans seemed not to notice the iPhone strapped to the belt of home plate umpire Derek Moccia, or his Secret Service-style earpiece. After each pitch, the phone relayed the call from the Trackman to his ear, delivered by the recorded voice of Pat Lagried, a public-address announcer who works part-time for MLB. Fans booed and jeered as normal when pitch calls didn’t go their way, though a few savvy hecklers, says Moccia, have updated their taunts, shouting “Call tech support!” or “Change the batteries!”

The most noticeable thing about the Atlantic League’s recent experiments is how easy they are to miss. An 18-inch-by-18-inch base looks about the same as the standard 15-by-15 when seen from the stands. This is by design. If the goal were simply to reduce strikeouts and increase balls in play, there are plenty of obvious interventions that would do the trick. But MLB isn’t willing to entertain things that might make a casual fan do a double take. The league’s list of rejected ideas, according to Sword, includes removing a defender from the field, making the ball bigger, and making fastballs down the middle count for more than one strike.

When the Atlantic League introduced the Automated Ball-Strike system in 2019, the optics were more jarring. It turned out that the strike zone in the rule book didn’t match the one that umpires called—which players, coaches, and fans had come to recognize. In the rulebook, the strike zone is 3D, the “area over home plate,” extending from the midpoint between a batter’s shoulders and belt at the top to the “hollow beneath the kneecap” at the bottom. Any pitch that touches this floating pentagonal prism, even if it drops in from above, is technically a strike.

When plugged into the Trackman, this produced some odd-looking results. Breaking pitches that veered wildly, sending the catcher lunging, were called strikes. In practice, Atlantic League umps judged pitches by where they crossed the front of the plate, and they rarely called pitches in the top of the zone strikes. For this season, MLB adjusted the Atlantic League strike zone to more closely match custom. It lowered the top, raised the bottom, widened the sides and, most significantly, made the zone into a two-dimensional plane that cuts through the middle of the plate, 7 inches from the front.

For the moment, the Atlantic League strike zone is 21 inches wide—4 inches wider than the plate—and runs from 27.5% of players’ listed heights at the bottom to 52.5% at the top. But MLB continues to tinker with its parameters, using ABS as an additional way to try to tune the game for action. “This zone is definitely tighter than anything I’ve experienced,” says Ducks reliever Barnes, who spent three seasons with the Toronto Blue Jays.

“I wish they had this ABS when I started out playing,” says Lew Ford, the Ducks’ 45-year-old designated hitter and hitting coach who played for six years in the majors. It would have been a big help, Ford says, to have a strike zone that didn’t vary from game to game and inning to inning. “For 20 years, every single at-bat I’ve had, the strike zone is different.”

On the flip side, the strike zone has been, for going on two centuries, the starting point for a conversation among players, coaches, and umpires that follows an unwritten etiquette. Some in the Atlantic League aren’t eager to give that up. “It sounds nice at first,” says Fields. “But when you actually go through it, I’d rather have that human error.”

“Anybody that is a true umpire—what I would call a gamer—we want the plate,” says Tim Detweiler, a regular behind the plate in the Atlantic League. According to baseball’s unwritten rules, a pitcher who demonstrates control of his pitches early gets to “expand the zone” in later innings, while a pitcher who misses the target set by his catcher is punished for the “missed spot,” even if the pitch catches the strike zone. “The game has always had this eye to it. Strikes look like strikes. Balls look like balls,” says Detweiler. “The computer doesn’t care.”

“I would never, ever want a robot to throw to—ever,” says Frank Viola, a 61-year-old pitching coach for the High Point Rockers, who pitched for 15 seasons in the major leagues, was named a World Series most valuable player with the Minnesota Twins, and lent a mustachioed grin to some canonical baseball cards. “I want to be able to stare an umpire down. I want to be able to yell at an umpire. I want an umpire to tell me to shut the hell up and just pitch.” During the first regular season game with ABS in July 2019, Viola gained the distinction of becoming the first coach ever to be thrown out of a game for arguing with the robot after Trackman issued a five-pitch walk that he disagreed with. “You can’t argue and beat a robot,” he says. “I mean, you could try your hardest, but I promise you, he’s not going to talk back.”

There are few more disorienting feelings on the mound, says Barnes, than throwing a pitch that you are certain is a strike and having the robot call it a ball. “Your whole idea of where the strike zone is gets thrown out the window.”

At this point, though, even the players, coaches, and umpires who aren’t thrilled with ABS are resigned to it. Atlantic umpires are independent contractors, employed at will. If they want these gigs, they have little choice but to go along. The word players use most to talk about ABS and the other rule changes is “adjustment.” It’s a mantra for independent league players. Slick infield? Sore ankle? Dank locker room? Make an adjustment.

The new mound distance is the most radical adjustment so far. MLB originally wanted to move the rubbers back by 2 feet. The plan was to do it in the second half of 2019, but Atlantic League owners, managers, and players—worried that it would lead to injuries—balked at the idea. “We wrestled with that for quite a while,” says White, the league president. That March, he appealed to the commissioner to postpone the change, and Manfred agreed.

In making its case to the Atlantic League for the reduced change this year, MLB said its research showed that the additional foot would not significantly alter pitchers’ mechanics but would give hitters a fraction more time to react, enough to make a 93.3-mile-per-hour fastball seem like 91.6 mph. But as the deadline approached this summer, some seemed to think that MLB might blink again. “I don’t even want to discuss the 1-foot mound-back rule because I think that will be the beginning of the end,” Viola said in early July. “That is just a monumental question mark right now.”

But MLB did go through with it this time. When I checked in with Barnes two weeks later, after he’d pitched a clean inning in his first appearance from the longer distance, he was less wary. “It’s not as big a difference as I thought it would be,” he says. He slightly adjusted the release on breaking pitches, he says, and otherwise hardly noticed.

This is a common pattern when leagues change rules: Outrage and handwringing are usually followed by shrugs. It happened, for instance, in 2018, when MLB instituted new limits on mound visits by catchers and coaches. “People were rolling their eyes,” says Epstein, who was then with the Cubs. “I think I might have, as well.” But after about three weeks of awkwardness, he says, people got used to it, and the number of visits eventually fell by half.

The pandemic has also reminded fans that nothing is written in stone. This season and last, MLB cut the number of innings for doubleheaders to seven and started any extra innings with a runner on second base in an effort to speed things up. While the changes were the source of plenty of bellyaching, and Commissioner Manfred has said they are not likely to endure into next season, the game of baseball survived.

So far, the Atlantic League experiments appear to be working as intended, helping to separate what works from what doesn’t. Last season, after trying it first in the Atlantic, MLB began requiring relief pitchers to either finish an inning or retire a total of three batters before they can be removed from the game. The Atlantic, meanwhile, was told to jettison an experimental rule allowing hitters to try to “steal” first base, regardless of the count, when pitches got by the catcher. Few hitters bothered to try it, preferring to test their luck at the plate.

The bigger bases are showing promise, according to MLB, with modest but not insignificant gains in batting average on balls-in-play, stolen base attempts, and stolen base success rates. The extended pitching distance also seems to be helping, with batting averages, runs scored and contact rates all rising in the two months since the change—though strikeouts, mysteriously, have also risen.

“Hopefully we can hit the right notes with some of these,” says Epstein, “and fans won’t even notice them, but they’ll notice the increased action and notice the game looking more like it’s traditionally looked.”

There is a school of thought—the old school—that says there’s nothing wrong with baseball that a little coaching couldn’t fix. Kids these days, according to this theory, don’t learn to play the game the right way: to shorten their swing with two strikes or to tap a grounder to the right side to move a runner over. “When I was growing up,” says Viola, “hitters did not go for a three-run home run with nobody on base. They got on base. They bunted them over. Then they sacrifice-flied them in. We actually had an understanding of what baseball is.”

Like many such nostalgic complaints, this obscures a deeper reality: The torpor within baseball has been there all along, waiting for teams to become sophisticated enough to discover it and for players to become skilled enough to exploit it. Now that they have hacked the game, the league is hoping to use the same statistical rigor to fix the problem it found. “To me, the root cause is the rules,” says Sword, “the dimensions of the playing field, the equipment, the essence of the game.”

Read next: How FanDuel Gained More Fantasy Sports Gamblers Than DraftKings

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.