Microsoft Learns Money Alone Can’t Fix Seattle’s Housing Mess

Microsoft Learns Money Alone Can’t Fix Seattle’s Housing Mess

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When Microsoft Corp. unveiled a $500 million pledge last January to tackle the housing crisis in the Seattle area, the event had most of the trappings of a product launch. During a slick presentation, President Brad Smith walked through the numbers: A booming economy had led to a housing shortage that was squeezing everybody whose wages couldn’t match Microsoft-level salaries. His company, then valued at $800 billion, had taken an interest in evening things out. “Every day for 40 years, we at Microsoft have benefited from the support of this community,” Smith said. “We want our success to support the region in return.”

The only thing the launch was missing was a fully fleshed-out product. Microsoft wanted help investing the money.

In the year since, Apple, Facebook, and Google have followed Microsoft’s lead, announcing splashy efforts to alleviate the Bay Area’s housing crisis. All issued outlines of plans that were short on details. Critics dismissed the moves as publicity stunts meant to deflect attention from the ways in which the industry has made surrounding communities less affordable.

If Microsoft’s experience over the past year is any gauge, the companies are approaching the task thoughtfully. But good intentions and careful investments won’t be enough to address a complex, urgent dilemma decades in the making. “We can’t expect that a couple of corporate gifts is somehow going to solve the problem,” says Jenny Schuetz, a fellow at the Brookings Institution who studies housing policy. “The scale of need is just so much bigger.”

On Jan. 15, Microsoft—now valued at more than $1.2 trillion—announced an additional $250 million line of credit to the Washington State Housing Finance Commission, along with several new projects and grants. The company’s efforts so far are expected to preserve or create more than 6,700 affordable homes, with about half the $750 million total yet to be committed. Still, even Microsoft acknowledges that it wants to pick up the pace. “There is great momentum,” says Jane Broom, senior director of Microsoft Philanthropies and one of four executives at the company who’ve been putting the pledge into action. “But we really do want to move faster.”

Last spring, Microsoft asked developers to present their best ideas for building and preserving middle-and low-income housing. “To be honest,” Broom says, “we were a little underwhelmed.” Most of the 15 or so proposed projects weren’t far enough along to fund, she says, or didn’t target the suburbs Microsoft wanted—within an hour’s commute of Bellevue, Wash., near its Redmond headquarters, areas where there are few affordable developments under way. The standout proposal was from the King County Housing Authority, which administers federal rental assistance and owns more than 11,000 units in the cities around Seattle.

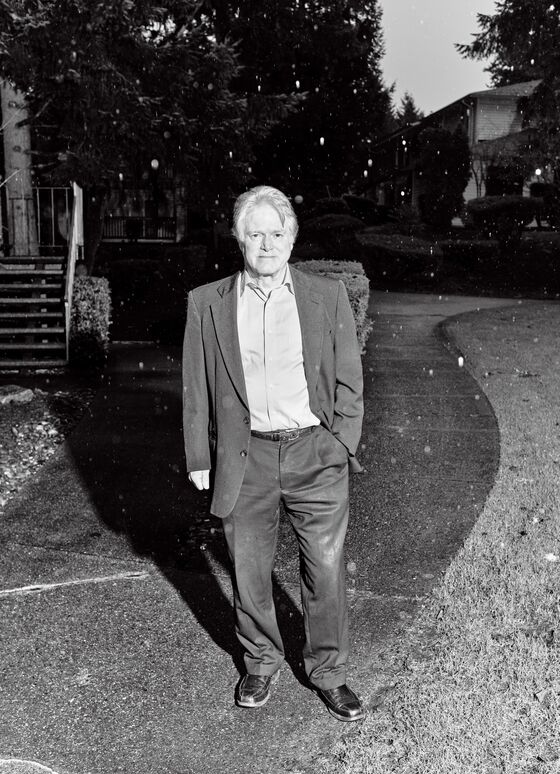

On a damp morning just before the new year, Dan Watson, the housing authority’s deputy director for development, stepped into a two-bedroom apartment at Kendall Ridge, a low-slung 1970s-era Bellevue complex. A cozy living room with thick brown carpet opened onto a clean but dated kitchen. It’s nothing opulent, but at $1,800 a month, it’s a good deal for a home on a rapid bus line in a Seattle suburb known for high-quality schools. In the age of Microsoft and Seattle-based Amazon.com Inc., comparably sized apartments in the neighborhood might go for $2,100 a month. “What happens is that big money takes on these places,” Watson says. “They’ll upgrade appliances, fixtures, cabinets, bathrooms. Then they’ll bump the rents quite a bit.”

Not at Kendall Ridge. Last year, Watson’s group used a $60 million loan from Microsoft (interest-only for 15 years at 1%) to help buy the complex and four other properties in the region. Its plan is to boost rents only as much as the housing authority’s operating costs rise—typically about 3% a year, vs. 5% to 8% a year for a market-rent increase in the area. Over time, that difference could add up, saving renters hundreds of dollars a month and keeping about 1,000 apartments markedly more affordable.

Such technocratic solutions don’t lend themselves to ribbon-cuttings, but they can be effective. Preserving a unit of affordable housing costs around $300,000 to $350,000 in the Seattle area, compared with more than $400,000 for new construction, says Stephen Norman, the housing authority’s executive director. Preservation, however, requires competing with aggressive private investors looking to gut units and start fresh. “When a property goes on the market, you have about three nanoseconds to put your money up,” Norman says. Microsoft’s money has helped his organization keep pace with higher prices.

Fixing the mess will require new housing, too, which means overcoming some tough math. In San Francisco, not far from where Apple, Facebook, and Google are based, it costs about $425,000 to build an affordable, family-size apartment, according to the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California at Berkeley. Land, fees, and other soft costs can add an additional 30% to 40%, says David Garcia, the center’s policy director.

The companies are looking to stretch their dollars across a wide range of projects in California and contribute land that can be used for residential development. But costs to build are so high that Google and Facebook, which each pledged $1 billion, say they’ll probably create only about 40,000 homes combined—in a state that needs millions of them.

None of this is entirely altruistic. In each case, much of the funding is structured as loans, so the projects will generate some kind of direct return on investment. Plus, the worsening housing crises in the Seattle area and Silicon Valley have started to hurt the companies’ ability to recruit. The pricing out of working-class populations (cops, nurses, firefighters) has rendered these areas less attractive. It’s much tougher for, say, schools to hire talented teachers who know they’ll be signing up for a 90-minute-or-longer commute each way.

While the housing money is helpful, the tech companies would create a more durable legacy if they worked to change policy. The federal government has pulled back dramatically from housing assistance, currently spending about a third of what it did in the late 1970s. Meanwhile, Nimby-influenced policies have all but outlawed construction of new affordable housing in many places. Large employers have an outsize ability to sway that sort of thing.

Microsoft’s pledge came along with a commitment from several suburban mayors to support pro-growth policies, such as increasing housing density near transit and reducing development fees. The company also backed last year’s increase to the state’s housing trust fund. “That was really the muscle of Microsoft,” says former Governor Christine Gregoire, whose group Challenge Seattle has worked with the company to advocate for more middle-income housing. Facebook has backed a controversial bill that would force California cities to rezone for higher density.

Corporate advocacy for such reforms is a relatively new phenomenon, says Schuetz, the Brookings researcher. She argues that the big tech companies’ focus on the issue could help convince people who’ve dismissed it as a concern only for the poor. “Talking about it draws more attention to it,” she says, “and puts more pressure on local governments.” —With Dina Bass

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeff Muskus at jmuskus@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.