Mexico’s Uneven U.S.-Powered Recovery Leaves Many Regions Behind

Mexico’s Uneven U.S.-Powered Recovery Leaves Many Regions Behind

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Diana Rivapalacio didn’t expect to be back on the factory floor two weeks after the pandemic hit.

When the Tijuana facility of Tokyo-based SMK Corp. shut down in April 2020, quality-control manager Rivapalacio and the business’s 800 machine operators, inspectors, and administrators headed home to uncertainty. But many were back at work that same month.

They had their city’s location on the U.S. border to thank for the rapid reopening. Like many manufacturing companies, SMK avoided a longer lockdown by making the case that one tiny product—a location tracker—was essential, Rivapalacio says. It could be used to trace shipments of vaccines or medical equipment, SMK told Mexican authorities.

Scores of companies across Tijuana found reasons to stay open. So did large parts of the rest of Baja California and other northern states, spurred by U.S. demand for Mexican-produced goods that had been supercharged by stimulus payments from the Trump and then the Biden administrations. “On the border we’re doing international business. They depend on us, and we depend on them,” Rivapalacio says. “At first it was a crisis, but everyone adapted.”

Other parts of Mexico haven’t been so lucky.

“Every sector is having a very bad time,” says Sergio Baños, mayor of Pachuca, the capital of Hidalgo, a mountainous state near Mexico City where the economy is dominated by wholesaling, retail, and services. In Pachuca, formal employment was down 12% in the second quarter of this year from the beginning of 2020. In Tijuana, it climbed 8%.

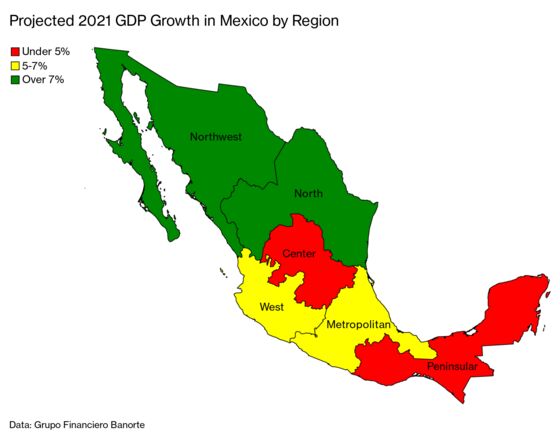

As Finance Minister Rogelio Ramírez de la O put it in a recent speech, “the economic recovery has been unequal among our regions.” By July this year, the northwest of Mexico had already moved far beyond its gross domestic product from 2018, the year before the country went into recession, according to Grupo Financiero Banorte, a Mexican bank. The center of the country, which is much more dependent on domestic demand than the north, was more than four percentage points behind its 2018 levels.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s own policies are partly to blame. Unlike many leaders, he didn’t push through any significant spending increases to help shore up households and businesses during the crisis, arguing that a lower debt load would help the country bounce back faster.

Growth along the border will power a 5.9% economic expansion across Mexico this year, following last year’s 8.2% contraction, according to forecasts by Bloomberg Economics. But the shape of the recovery is the opposite of what López Obrador was hoping for when he took office in 2018, promising to battle inequality and wean Mexico off its reliance on foreign companies.

The U.S.-China trade war initially seemed to highlight the risks of being so reliant on foreign trade, as the cost of procuring foreign supplies rose, starting in 2018, and shipping fees caused further price hikes in 2021.

Tijuana rebounded swiftly, though, as some U.S. companies, contending with snarled supply chains, shifted operations to Mexico. North American manufacturers said, “‘we have to make a change in our business, because we can’t hold a product worth millions or billions because one component didn’t arrive from Africa, Asia, or Europe,’” says Carlos Higuera, the chief executive officer of PCM Corp., a Tijuana-based contract manufacturing company.

New factories are going up thanks to an influx of foreign capital. Last year the floor space of Tijuana’s industrial companies grew the most in at least a decade, says Edna Patricia Hernández, CEO of Tijuana EDC, a nonprofit that assists international companies working in the city.

Meanwhile, in Pachuca, business at José Zaragoza’s construction company, Cayco Construcción, is down 40% compared with 2019. While the local economy is recovering, invoices are constantly going unpaid because of a lack of liquidity. “We have few resources to work with, an incomplete workforce or payroll, and aren’t being paid in advance to be able to produce or contract or get things moving,” Zaragoza says.

Where Tijuana’s exposure to the U.S. helped it benefit from the country’s huge stimulus packages, Pachuca’s greater reliance on domestic demand meant it suffered from López Obrador’s decision to not to hike spending, says Zaragoza, who’s head of the local chapter of the business association Canacintra. Government stimulus wouldn’t “have solved everything, but it would definitely have helped companies perhaps to maintain their payroll, perhaps not have to close, or perhaps to keep up their liquidity levels,” he says.

Hidalgo’s economy contracted more than twice as much as Baja California’s last year and is set to grow only 2.8% in 2021, according to Banorte, while the northern state is expected to expand by 8.2%.

At the same time, Mexico’s poverty rate climbed two percentage points from 2018 to 2020, to 43.9%. The spike “was hand-in-hand with the lack of a real pandemic-driven economic support for families,” says Ana Gutiérrez, an economist at the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness, a think tank.

The president’s closefisted policy has paid off in other ways. When López Obrador, a populist with leftist roots, took office, markets panicked, worrying he’d send the country into an economic tailspin. Investors now give him high marks for fiscal rectitude. Colombia’s credit has been cut to junk by two ratings firms this year, but few analysts see a risk of that happening to Mexico.

López Obrador’s unexpected pragmatic streak also saw him prioritize vaccinations in the north—despite it being far from his voter base—in a so far unsuccessful effort to persuade the U.S. to open the border.

Mexico’s overall GDP won’t return to 2018 levels until 2023 at best, according to Banorte economist Delia Paredes. A look around Tijuana’s smaller companies shows the recovery hasn’t been uniform there either.

Local businesses that aren’t seeking to export are kneecapped by supply chain problems and low demand, partly because of the border closure. Juan Carlos Pérez, who for two decades has sold Styrofoam containers and paper bags out of his supply store in Tijuana, says his sales are running at 70% of normal levels. His workforce has dwindled from seven to three.

“We’ve managed to survive, because we have years in the business, but those who were just starting out—they didn’t have the means to stay open,” he says.

Read next: How Mexico Forgot Its Covid Crisis

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.