How Mexico Forgot Its Covid Crisis

How Mexico Forgot Its Covid Crisis

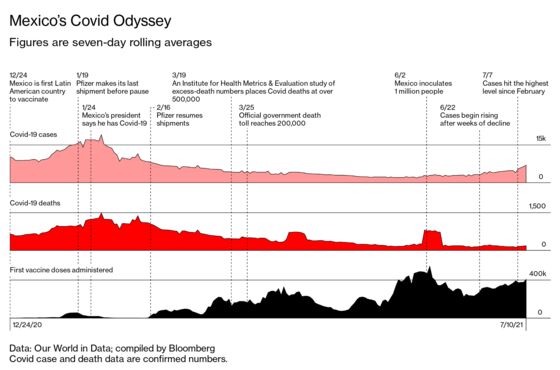

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Every weekday morning, Mexico’s president holds a rambling televised celebration of his supposed successes: a news conference with special guests, video clips, and slick graphics that often has the air of a variety show. Until mid-January one of the favored features was a giant graphic that showcased Mexico’s undisputed progress as the first Latin American nation to vaccinate its citizens against Covid-19. Then the data turned bad. Pfizer Inc., at the time Mexico’s only supplier of Covid shots, halved, then completely stopped, deliveries. Vaccinations remained unchanged for almost a month; deaths surged. The vaccine tracker got yanked from the show.

Mexican viewers didn’t know it from watching President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s daily discourse, but Mexico was becoming one of the world’s deadliest Covid hot spots. The government’s alternate version of reality included an undercounting of cases and deaths, something it belatedly acknowledged in March when it announced that Covid-related deaths were far higher than the official count, which stood at about 234,000 as of July 5. More expansive estimates can be derived from excess deaths, the epidemiological term for increased mortality compared with an average year. In one such analysis, the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics & Evaluation places Mexico’s Covid deaths at about 540,000.

During his morning broadcast on Jan. 18, López Obrador swerved around an uncomfortable truth: Pfizer had just shunted Mexico to the back of the line for limited supplies while it closed a plant in Belgium for upgrades. He spun a different tale: that he was altruistically acceding to a (nonexistent) request by the United Nations to give up shots so Pfizer could boost production to supply poorer nations “that don’t have the economic possibility to buy vaccines.” AMLO, as the president is known, claimed that he approved the Pfizer cut because “it would be unjust and inhumane and contradictory” not to. “We have to walk together, be supportive,” he said. On his YouTube channel, the news conference was titled “Redistribution of Covid-19 vaccines is an act of solidarity.”

What was actually happening was entirely out of Mexico’s hands. Yes, Pfizer’s retooling of its Belgian factory would eventually lead to greater global supply. But in the short term, the company made decisions about where it would send its vials and where it wouldn’t. It chose to make cuts in Latin America and Europe while sending millions of shots to Israel. The difference was that Israel had just signed a data-sharing deal with Pfizer, which would flood the country with its vaccine to test its real-world effectiveness—good for science and, of course, Pfizer.

The methods of estimating Covid’s true death toll vary, but study after study show Mexico among the world’s hardest-hit countries. For average monthly excess deaths during the pandemic, Mexico is third, behind Ecuador and Peru, according to a Bloomberg analysis of figures collected by Our World in Data. (As of July 6, Mexico has about 54% more deaths on average than over the previous five years; Ecuador is at 67% and Peru at 136%.) In other published tallies, Mexico has ranked third or fourth in the world for total excess deaths. The president’s office and the health ministry didn’t respond to requests for comment about the government’s handling of the pandemic.

Last winter the carnage in Mexico City was palpable. Black smoke billowed around the clock from overwhelmed cemetery crematoriums. Funereal bottlenecks forced families to take the remains of their loved ones to other parts of the country for timely disposal. In hospitals the bodies were backlogged on gurneys and in autopsy rooms. It took until May for Mexico’s hospitalizations to drop to 13% of capacity, from 90% in January, and the positivity rate, once the world’s highest at roughly 50%, to fall to 17%.

“Many patients didn’t have a chance to even make it to a hospital or wound up in a hospital that wasn’t prepared,” says Francisco Moreno, head of internal medicine at Centro Médico ABC, one of Mexico’s most prestigious private medical institutions. “What I saw was a total collapse of the health system.”

And yet, to the world and even some Mexicans, it’s almost as if it never happened. If you didn’t know that an extraordinary number of people had perished only months ago, it would be easy to see just another sunny summer on the horizon, with bustling boulevards and packed beaches. Some of this collective amnesia is due in part to the actions AMLO never took: While Europe is publicly wrestling with how to reopen to foreign tourism, Mexico never closed air travel from any countries or required any testing or quarantines from visitors. But the forgetting doesn’t mean it didn’t happen—or can’t happen again, soon.

Mexico’s first mistake, and probably its biggest, was its coronavirus testing plan. As part of its initial pandemic response in March 2020, AMLO’s government didn’t offer tests unless a patient had symptoms. The method’s power to obscure was the envy of then-U.S. President Donald Trump. “I want to do what Mexico does. They don’t give you a test till you get to the emergency room and you’re vomiting,” Trump groused to top aides last summer, the New York Times reported.

Mexico’s strategy, which has never officially changed, both failed to keep the virus’s spread in check and meant the country’s death toll escaped wide notice. When researchers tried to put together more accurate numbers, the government erected barriers. Some researchers had been able to cobble together a rough count of excess deaths in Mexico City based on death certificates, having noticed they were sequentially numbered. The idea was, if you know the latest number on the certificates, you know how many are dead. In March the authorities thwarted that workaround: The certificates were no longer searchable by number, only by name. There are no longer independently available statistics on excess mortality.

Mexico’s second big mistake was AMLO’s refusal to raise debt to pay for fiscal stimulus or aid to the poor, as the leaders of most major economies did. This reflected the economic quirks of the president himself, who’s never possessed a credit card in his name. The son of fabric shop owners from the state of Tabasco, AMLO has shunned luxuries and refused to fly on the presidential Boeing 787 Dreamliner—he’s been trying to sell it from his first day in office. His political philosophy was shaped by the disastrous debt default of 1982, which brought inflation to 115%, and the Tequila Crisis of 1994, which produced a sudden devaluation of the peso and a recession.

His government’s spending commitments for Covid relief amount to about 0.7% of gross domestic product—less than a third of the average for other developing countries in the Group of 20, the International Monetary Fund says. And those programs have largely been microloans to small businesses. While other countries essentially paid workers to stay home and supported companies so they could preserve jobs, Mexico’s policies had the effect of keeping people in circulation to earn a living.

Arturo Herrera, AMLO’s outgoing finance minister, argues that the administration saved Mexico from weakened public finances that would have had worse repercussions down the road, leading to cuts in social services. Had Mexico spent like Canada or Germany did on Covid stimulus, he said in a February interview with Bloomberg News, the additional debt would have exceeded all government funding for public universities and high schools. AMLO has also argued that his government inherited a broken hospital system and had to expand its capacity in a short time period to handle the health crisis, which is where it focused much of its attention, rather than on testing.

Throughout the first wave, in the spring and summer of 2020, Hugo López-Gatell, the nation’s virus czar, kept saying Mexico was beating back the outbreak, though it wasn’t. “The epidemic is slowing down,” he declared in a May 5, 2020, news conference. “We’ve flattened the curve.” When confronted with data showing the curve was in fact continuing to go up, he said what he really meant was the slope would have been steeper if it weren’t for the social distancing policies he’d implemented. When a second wave of infections hit Mexico City toward the end of 2020, he and the mayor resisted ordering a shutdown, even as the city’s hospitals overflowed with patients. In January the government denied that the capital’s hospitals were full. Yet Bloomberg News found that paramedics had to drive their ambulances around through the night to find scarce unoccupied beds.

The midnight searches for beds were among the worst tales the city’s doctors, nurses, and paramedics described during the height of the second wave. One patient waited 11 hours in an ambulance, running through several oxygen tanks, until a bed was available. A medic drove a patient six hours to Aguascalientes state, northwest of Mexico City, to find a bed. A hospital ran out of the medication it used to sedate patients being fitted with ventilators.

Doctor Gerardo Ivan Cervantes, head of epidemiology at Hospital MAC, in the central Mexican city of San Miguel de Allende, describes a harrowing event at another facility. Suddenly four patients couldn’t breathe on their own, sending the hospital into a scramble to buy ventilators for them. As staff searched for the equipment, doctors took turns manually pumping oxygen into the patients’ failing lungs with hand-squeezed bag masks. “There were four people pumping for each patient,” Cervantes says. “It’s too tiring for just one person.” The effort dragged on until the ventilators arrived four hours later.

For Cervantes, it was just one of many long stretches in close contact with the coronavirus; he treats more than 10 Covid patients a day. Months later he’s in another long stretch: waiting to get a vaccine.

Mexico was on the cusp of hope on Christmas Eve. On the holiday known as Nochebuena, or the Good Night, it became the first nation in Latin America to administer a Covid vaccine. Broadcast from a Mexico City hospital, intensive-care nurse María Irene Ramírez got the Pfizer shot in her arm. The country couldn’t have been more grateful.

A week later the New Year’s adventures of virus czar López-Gatell provoked doubts about the Mexican government’s credibility in leading the way out of the crisis. Before the holidays, López-Gatell, who’s also deputy health minister, had told citizens to stay home to curtail infection. Yet in a photo taken on Dec. 31 as he boarded a flight to the beach resort of Huatulco, López-Gatell, ready for relaxation in a tennis cap and gray fleece, is seen standing with his mask pulled below his chin, talking on his phone. The photo went viral on Mexican social media, followed by a second shot of him sitting under the thatched roof of a beach restaurant with a woman, both of them maskless, as waves broke onto the nearby sand.

López-Gatell defended his actions, saying he went to visit family and obeyed local restrictions, which were more relaxed than those in Mexico City. On Jan. 6, AMLO praised him in his daily televised news conference, calling him “honest, honorable” as the epidemiologist’s smiling face was projected onto a wall. AMLO called attention to his czar’s studies at Johns Hopkins University. “A doctorate and a postdoctorate from this prestigious U.S. university. One of the most prestigious!” he said. “On top of that, he’s a specialist in pandemics, prepared—and cultured.” The episode reached a predictable end weeks later when the Covid czar himself became ill with Covid.

In the midst of this came the almost-monthlong Pfizer drought, which began after the shipment of Jan. 19. According to an analysis performed for Bloomberg Businessweek by epidemiologist Shaun Truelove at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, the loss of vaccines during that critical period resulted in about 3,500 deaths in Mexico. “Imagine the uncertainty at that moment,” says Deputy Foreign Minister Martha Delgado. “If you don’t have any for three weeks, even if it wouldn’t have been a large amount, it was very onerous, above all because of everything we had prepared, the entire vaccine operation. And public opinion.” Pfizer said in a statement that it advised governments in advance of the factory upgrade and completed it in two weeks. The upgrade allowed the company to meet global delivery commitments in the first quarter and exceed them in the second quarter. It also contributed to Pfizer’s ability to revise its projected 2021 global output from 1.3 billion doses at the start of the year to its current target of 3 billion, the company said.

After Pfizer’s delay, Mexico scrambled to strike vaccine deals with China, Cuba, and Russia. AMLO had himself caught Covid and was convalescing at his presidential residence on Jan. 25 when he held a call with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Mexico did a fast-track approval of the Russian Sputnik V shot. On Feb. 2 the Mexican government said it had secured 1.4 million doses of Sputnik, an additional 8 million of China’s CanSino Biologics vaccine, and up to 2.7 million AstraZeneca shots through Covax, the global distribution program for poorer countries.

On Feb. 8, just days after AMLO returned to work, he announced that he’d struck deals with China’s ambassador to Mexico for additional Chinese vaccines. In another deal, his government started negotiating with Cuba to participate in trials of a vaccine developed there. On Feb. 14, Mexico received 870,000 AstraZeneca doses from India. That let Mexico start vaccinating its older adults.

Pfizer doses, 491,400 of them, finally arrived on Feb. 16 on DHL jets from Belgium. By then, Mexico’s daily deaths had doubled since the start of the year, to a record high of 1,800. But the vaccine campaign relaunch was problematic. AMLO, the man who disdains urban elites, made a show of sending shots to remote mountain villages and to every state, instead of focusing on urban infection hot spots.

And though they’ve pocketed Mexico’s money, some pharmaceutical companies haven’t yet delivered, in part because of global production problems but also because they put Mexico toward the end of the line. AstraZeneca Plc has delivered just 28% of the doses it pledged will reach Mexico by the end of August. Russia has sent just 4.1 million of the 24 million Sputnik doses AMLO initially said had been promised by the end of March. Pfizer appears to be on track, having sent almost two-thirds of the doses due by yearend. Mexicans’ desperation for the shots has at times been comical; there have been reports of people in their 30s dyeing their hair and eyebrows gray and using fake IDs to try to get shots meant for senior citizens. It’s also driven hundreds of thousands of wealthier Mexicans over the border to receive shots in the U.S. Mexico’s travel agent association says members have sold more than 170,000 vacation packages to people looking to fly to get shots.

Front-line medical workers were supposed to be vaccinated first, but many are still waiting. That includes Cervantes, the physician who squeezed a bag mask for four hours to keep patients alive. On May 8 he stood in line at a facility in Guanajuato state from 6 a.m. to 3 p.m., when it ran out of shots. He returned home unvaccinated, and perhaps even more in danger because of the crush of hopeful medical workers. “We were exposed, because the line was long and there wasn’t room to keep our distance,” he says. As of press time, he still hadn’t been vaccinated.

On March 22 news broke that more than 1,000 people in the Yucatán Peninsula’s Campeche state had been injected with fake Sputnik vaccines. Recipients included executives, politicians, taxi drivers, and workers at a factory assembling export goods. No one appears to have been hurt, but there was reason to believe the incident was part of a wider problem.

Five days earlier, Mexican customs agents and soldiers searching a private airplane at the Campeche airport had found a white cooler chest wedged between two seats. In the chest were sodas, an ice cream sandwich, and, farther down amid the ice cubes, a plastic bag filled with vials of what appeared to be the Sputnik vaccine. In all, the cooler, plus a second one found on board, contained 1,155 vials, with the equivalent of 5,775 doses. The Russian company that distributes Sputnik said the vaccines were fake. The aircraft’s destination, according to the Mexican military, was Honduras, raising the possibility that any fakery has gone regional.

People don’t take a chance on black-market vaccines when they believe their government is ready and able to take care of them. The UN’s Mexico office has issued fraud alerts about people posing as UN or World Health Organization officials trying to sell vaccines. Mexico’s health regulator warned against WhatsApp alerts that tell older adults false places to get shots in Mexico City.

It was in May that things began to feel normal in Mexico. By early June the country was administering doses from six different vaccine makers, including CanSino and AstraZeneca shots that are locally produced (and, in the case of AstraZeneca, exported regionally after a long delay). Pfizer had increased deliveries. Vaccine distribution had been adjusted so more doses were going to places with more cases. Covid clinics were shutting down, testing centers offered discounts, and Mexico City had lifted almost all restrictions—the city was excited by reports that concert halls and other cultural institutions would open soon. On June 2, 1 million vaccinations were given, and by the end of the month, about 26% of the population was covered with at least one shot. In an example of what the government can accomplish when the incentives are sufficiently powerful, 79% of adults in Baja California had received at least one dose. The goal is to open the border with California.

That foreign tourism never stopped only bolsters the sheen of normalcy (though the inaction probably helped bring in the virus via U.S. beachgoers). And the lack of regulations to reverse just helps feed the national amnesia. For those who survived, the president’s relentless optimism has largely worked. The latest polls show an approval rating of 56%. AMLO’s vaccination program has an approval rating of 62%.

As June turned to July, though, uncertainty returned. Variants of the virus are devastating parts of Latin America, and indications are that Mexico might not escape another wave. On three consecutive days in early July, Mexico City recorded case counts not seen since February. Moreno, at Centro Médico ABC, says he now has 32 hospitalizations, up from eight a few weeks ago, though down from the winter peak of 75. The concert halls didn’t open after all. Mexico needs a plan. Adjusting the content of the president’s programming may not be enough. —With Stephanie Baker and Sebastian Boyd

Read next: When Lifesaving Vaccines Become Profit Machines for Drugmakers

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.