Can Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer Save Europe?

Can Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer Save Europe?

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The annual Ash Wednesday political roast in the northern German town of Demmin is classic partisan shtick: Beer flows freely, the aroma of sausage fills the air, and assembled grandees make lame jokes about their rivals. Chancellor Angela Merkel had been a regular at the event for two decades, but this year she skipped it, ceding the headline spot to her handpicked successor as leader of the country’s ruling Christian Democratic Union, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer.

A slight woman with a pixie haircut, Kramp-Karrenbauer—whose name is routinely shortened to AKK—was elected in December to succeed Merkel at the helm of Germany’s center-right party. While Merkel remains chancellor, this puts AKK in line to take over for the longtime ruler in 2021, when Merkel’s term ends, or sooner if she’s forced out.

Since assuming the leadership, AKK, 56, has stormed across Germany’s political landscape, seeking to establish her bona fides with conservatives put off by the CDU’s leftward drift and to shed her image as a Merkel disciple. Her fiery speech in Demmin couldn’t have been more different from Merkel’s usual plodding rhetoric. Already under attack for an off-color joke she’d made at an event a few days earlier—about Berlin’s culture of “third-sex bathrooms, for men who don’t know whether they should stand or sit while peeing”—AKK raised the stakes by further ripping into political correctness. Requiring people to “weigh every word on a jeweler’s scale” threatens to quash robust debate and destroy cherished traditions, she said. In response to news reports about a Hamburg school that had barred students from wearing American Indian costumes, she roared, “I want to live in a country that allows children to be children, to dress like Indians.” The crowd erupted in applause.

AKK and Merkel both rose to power in an alpha-male culture and share a sensible political style, but their differences run deep. Merkel, a former physicist who grew up in East Germany, navigated her early political career around the collapse of the Berlin Wall and served as head of multiple ministries for Helmut Kohl, the CDU chancellor who led the country through reunification. She became the party boss in 2000 and five years later led the CDU to a general election victory.

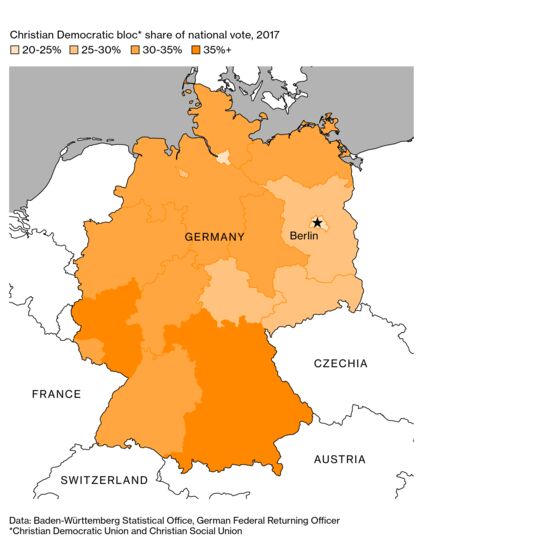

Before taking the reins of the CDU, AKK had little political experience beyond her tiny home state of Saarland, a 1,000-square-mile patch of wooded hills, shuttered coal mines, and struggling steel mills near the French border. But she’s also much better at the flesh-pressing and baby-kissing parts of the job than Merkel is. While Saarland leans left, AKK managed to win two elections there against the Social Democratic Party (SPD), which had governed the state through the 1990s and appeared poised to return to power.

Her victories are all the more remarkable given her vocal opposition to policies such as gay marriage (legal in Germany since 2017) and her support of obligatory national service. “She weighs her decisions carefully and brings others along with her,” says Monika Bachmann, the CDU’s social services minister in Saarland, who served in AKK’s government there. “She loves to talk to people on the street, and she listens.”

Following in Merkel’s footsteps, though, involves more than just delivering electoral victories. Merkel has served as the symbolic keystone of European liberal democracy for the past decade, helping the European Union navigate the global financial crisis, the near collapse of the euro, and waves of Middle Eastern and African refugees. Since then she’s lost support from the CDU’s right wing and been forced to form a coalition government with the SPD. Meanwhile, the even-further-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party has been picking off the most conservative voters. France’s Emmanuel Macron has tried to step into the breach with pan-national plans for reform, but he faces his own electoral challenges at home.

AKK has distanced herself from the French president, warning of the danger of a European “superstate.” She’s also taken aim at the White House, telling Bloomberg Television at the World Economic Forum in Davos that President Trump’s adversarial political style “makes it more difficult to work together.”

Her critics argue that she lacks the policy chops to deal with an economic downturn, which some indicators suggest may be on the horizon. “AKK is a professional with great instincts,” says Oliver Luksic, a Saarland legislator in the Bundestag for the Free Democratic Party. “But she’s not very competent when it comes to Europe and the economy. If she were confronted with another euro crisis, she’d find herself in unfamiliar territory.”

AKK was born into a conservative Catholic family in Püttlingen, a shabby former mining town of 20,000 about 25 minutes by car from Saarbrücken, the charming but not very cosmopolitan capital of Saarland. Although AKK professed a passion for the Scottish boy band the Bay City Rollers as a teen, she was more energized by conservative politics and joined the CDU in high school.

At 22, AKK won a post on the city council of Püttlingen. She became the local CDU chairwoman and a state leader of the party’s youth wing a year later and quickly earned a reputation as a bridge builder with a “rational and pragmatic political style,” says Rudolf Müller, who as Püttlingen’s mayor encouraged her to run for office. When a local factory closed in the 1980s, he recalls, AKK worked with members of the local Communist party to create a training center that helped the 150 laid-off workers find jobs. In 1999, after several months of filling in for a retired member of the Bundestag, she won a spot in the state parliament and later ran a handful of ministries.

When she rose to become Saarland’s premier in 2011, AKK confronted a state in turmoil. There was surging unemployment, a steel industry in sharp decline because of competition with China, and a budgetary shortfall as big industrial companies saw their profit—and their tax bills—plummet. She cut salaries for civil servants and reined in other public spending. Then, as thousands of mining jobs evaporated, she insisted on including labor representatives in talks with employers, helping to ensure that many former coal miners retired comfortably or found jobs in renewable energy. During the 2015 refugee crisis, she got credit for Saarland’s well-ordered shelter system. She simultaneously backed the rapid repatriation of asylum-seekers whose bids were rejected—a nod to the party’s right wing and a far tougher position than Merkel held at the time.

AKK’s fans point to her time in Saarland as proof of her tenacity. Peter Jacoby, the state’s former finance minister who’s known AKK for more than 30 years, cites the way she persuaded wealthier German regions to divert €500 million ($565 million) in extra money to the struggling state in 2017. “AKK has already gone through the fire of political crises,” he says.

She also learned how to outmaneuver rivals. Eight years ago she was accused of grossly underestimating the cost of a museum expansion in Saarbrücken, and the Social Democrats convened two parliamentary committees to investigate her role in pushing the plans despite exploding costs. At the time, AKK headed a government of Greens and economic liberals, but when the inquiry started, she scuttled that coalition and formed an alliance with the Social Democrats instead. The probes were wrapped up quietly, and no charges were ever filed.

If things had gone as planned, AKK would’ve had several years to prepare for the global stage, but setbacks in regional elections last fall and festering tension over Merkel’s formerly open-door policy for refugees forced the chancellor to surrender the party leadership. Although it’s possible Merkel will serve out her term, the Social Democrats’ commitment to the coalition is fragile. If they were to pull the plug, AKK would be the leading candidate for the chancellery.

The concerns AKK dealt with in Saarland—ensuring that the high-speed train from Frankfurt to Paris passed through the state capital, managing the decline of the local coal industry—bear little resemblance to issues she’d face as chancellor. Growth this year is forecast to be the weakest since 2013. Industrial output fell 3.3 percent in January from a year earlier, and the country narrowly avoided a recession at the end of 2018. Highways and bridges are crumbling, the population will start shrinking in the coming decade, and the crucial auto industry risks being sidelined by self-driving electric cars. Finance Minister Olaf Scholz recently said, “The fat years are over.”

Even as she’s been making many of the party’s day-to-day decisions, AKK has been in an unofficial but intensive chancellor-training program. She’s become a staple of the 24-hour news channels and is frequently seen on weekend political chat shows holding forth on the economy, refugees, and relations with the EU. In December she discussed Brexit with Prime Minister Theresa May at the British Embassy in Berlin. In January she made the rounds at Davos and met Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar to preview European parliamentary elections. She was off to Brussels in March to help formulate a response to the virulent nationalism of Hungary’s Viktor Orban. She’s taking English lessons, the better to defend liberal democracy on the global stage.

For as much as she’s tried to differentiate herself, AKK isn’t abandoning the Merkel model entirely. As she hit her stride at the Demmin Tennis Center, AKK set aside the beer jokes and the culture war dog whistles to address a topic more typical of the chancellor’s speeches: the breakdown of the post-World War II global order. Aiming far beyond the coal mines and ribbon cuttings of Saarland, AKK weighed in on European parliamentary elections, EU defense policy, and President Trump’s decision to withdraw from a 1987 nuclear weapons treaty with Russia. That decision means Europe is “once again the plaything” of Cold War behemoths, she said. “We don’t want that—and that’s why we need Europeans to step up.” The crowd responded with no less vigor than it had to her pronouncements on political correctness, a positive sign for those who’d like to see the European experiment continue. Her handlers might also have been relieved: Their training, it seems, is working.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Bret Begun

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.