Mental Health Is Still a ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ Subject at Work

Mental Health Is Still a ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ Subject at Work

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Aaron Harvey is co-founder of Ready Set Rocket, a boutique advertising firm that’s done campaigns for fashion brand Michael Kors, pop star Rihanna’s fragrance, and upscale salad eatery Sweetgreen. He knows how to sell a lifestyle that people want to associate with. He’s also spent decades secretly living with a rare form of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Fed up with a corporate world in which it’s not OK to talk about that, he’s applying his branding skills to a topic that people generally try to avoid: mental health.

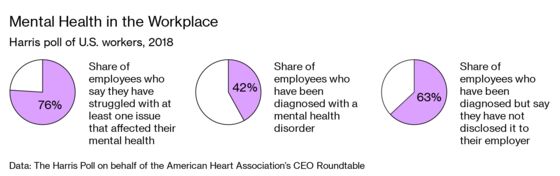

Since the dawn of the corporate office park, mental health has been relegated to the “don’t ask, don’t tell” limbo of the American workplace. People who’ve been diagnosed with a condition such as depression or anxiety aren’t inclined to open up to bosses and colleagues. Shame and stigma prevent some 80% of sufferers from seeking help, according to one report. These are expensive problems to keep hidden. Depression alone costs the U.S. economy $210 billion a year, half of which is shouldered by employers in the form of missed work and lost productivity.

As a business owner, Harvey thought he’d established a culture that was supple enough to deal with all employee challenges. His firm offers unlimited time off and the flexibility to work remotely as needed. It takes a shared, rather than top-down, approach to decision-making. Ready Set Rocket has been named Crain’s and AdAge’s best place to work. So Harvey was humbled by what happened when the company experienced a mental health crisis in its ranks. An intern started acting erratically, going into meetings uninvited and shouting before someone was able to get an emergency responder to take him to a psychiatric ward. The office’s confused handling of the incident exposed a weakness in its approach to mental health, a gap Harvey is convinced exists throughout the corporate world. “We are a small, pro-mental-health-culture company,” Harvey says. “If we don’t know how to do this, no one knows.”

Seeing that the discussion around mental health was being informed, and shaped, by individuals sharing their experiences, Harvey started the site Made of Millions. It curates stories from people with a range of conditions. The site’s three-person team published a guide in February, Beautiful Brains, to help employees push for better dialogue about mental health in the office. To get the message out through social media, Harvey and his team started the #DearManager campaign, encouraging workers to share the guide with their human resources departments. From the data he’s seen so far, employees at companies including Goldman Sachs Group, Deloitte, Accenture, and Verizon Wireless have downloaded it.

The creation of “best practices” has thus far been left to the handful of business leaders like Harvey who care about the issue. Many companies don’t even know how to start the conversation, and there’s no playbook to follow. Benefits managers compare notes through initiatives led by organizations such as the Kennedy Forum, a mental-health-focused nonprofit, to guide one another through the darkness.

While there are laws to protect people with mental health issues from discrimination, the pervasive stigma around those conditions has limited their usefulness. Every avenue that exists has its shortcomings: The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission takes up cases on behalf of workers who feel they’ve been discriminated against as a result of their mental health. The agency tries to resolve cases via mediation, which doesn’t create binding precedents. Even when it sues successfully, it rarely wins the kind of payouts that would force a broad change in corporate behavior. Individual companies rely on their HR departments to field complaints, but a worker’s comfort level in broaching sensitive topics with HR is wrapped up in how much they trust their employer. When those avenues fail, a person can turn to the courts. That, however, can come at great expense and with public exposure.

The Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA), a 1990 law designed to protect employees with health conditions against discrimination (assuming they can perform the essential tasks of the job), requires companies to offer accommodations if needed. When the legislation was being hashed out in the late ’80s, Republican Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina fought to exclude people with certain mental health problems from its protections. His effort failed but highlighted the pervasive bias against people with mental health conditions that lingers to this day.

Three years after the law was passed, New York Law School professor Michael Perlin warned that it wouldn’t be effective if people’s attitudes toward mental health didn’t change. “No matter how strongly a civil rights act is written nor how clearly its mandate is articulated, the aims of such a law cannot be met unless there is a concomitant change in public attitudes,” he wrote in the Journal of Law and Health.

As the ADA wound its way through the courts in the ’90s and early 2000s, it became clear that judges thought of disabilities as permanent conditions rather than ones that manifest in episodes, according to Tom Spiggle, an employment lawyer. That view largely excluded people with mental health conditions, which often flare up intermittently. In 2008, Congress voted to expand the ADA to include conditions that manifest periodically, which helped improve protections for people with conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, and depression.

That same year, Congress passed a law requiring insurers that provide mental health coverage to offer the same level as their medical benefits. While many insurers comply on paper, their provider directories are often filled with therapists who aren’t taking new patients or are no longer in the plan.

To deal with the problem, employers have been expanding employee assistance programs. Insurer Hartford’s Chief Executive Officer Christopher Swift took a look at his company’s mental health programs and noticed a 30% jump in the use of EAP counseling sessions in 2018 from the previous year. So the company decided to offer its 19,000 workers double—10 free sessions instead of five—and started reimbursing them for out-of-network mental health care at in-network rates. “What employees value today is a more holistic approach to an employer benefit,” he says.

Chevron Corp. is trying to provide help where services might be otherwise scant. Some of the energy giant’s workers are out on remote, 28-day rotations away from their families, doing jobs that “can be very stressful based on how sensitive the type of work is that they’re doing,” says Brian Walker, Chevron’s manager of EAP Work Life Services. “This may trigger other mental health conditions.” Chevron has also decided to be more forgiving toward people who fail alcohol or drug tests, as long as there isn’t a safety issue. “If we can get them out of the work setting, get them education, and treatment, and support,” says Walker, “the person can come back and contribute 10 to 15 more years.”

Cisco Systems Inc. gives its employees emergency days off for the things in life that wouldn’t classically fall into “sick” or “vacation” days. Microsoft Corp. offers workers 12 free counseling sessions and is building on-site counseling services. “I think the demand will always exceed our ability to add capacity,” says Sonja Kellen, senior director of global health and wellness benefits at Microsoft.

Lyft Inc., the ride-hailing company, has made mental health care entirely free. Through a service called Lyra Health Inc., corporate employees can see counselors for any mental health issue or even marriage counseling. “There is a war for talent,” says Nilka Thomas, vice president for talent and inclusion at Lyft. “Supporting your workforce supports your bottom lines. It’s not only the smart and human empathetic thing to do—it’s the smart business tactic as well.”

Yet only a small fraction of eligible employees use EAP programs, according to one study. And they don’t solve the glaring gaps in care that exist. Without offering better insurance coverage, “you’re just sending more people out into an inadequate system,” says Henry Harbin, a psychiatrist and adviser to the Bowman Family Foundation, which works on mental health issues. “You the employer are basically not helping your employees get access to effective treatment, much less affordable treatment.”

Improving mental health benefits has been a priority for Michael Thompson, CEO of the National Alliance of Healthcare Purchaser Coalitions, which represents 12,000 employers that spend $300 billion a year on health care for 45 million people. Inadequate networks, in particular, are a problem, he says: “When you compound that with the fact that often people who are experiencing issues with mental illness are in denial, and then you put these barriers in front of them, it’s no wonder suicide rates are rising.”

The recognition that mental health is a pressing workplace issue extends beyond the corporate world. In August the New Jersey attorney general signed a directive to promote resiliency in its ranks saying “protecting an officer’s mental health is just as important as guarding their physical safety.” There were 37 law enforcement suicides in the state from January 2016 through mid-2019, according to one study.

The suicide rate among doctors is more than twice the national average. The American Medical Association has acknowledged that doctors are less likely to seek therapy for fear of jeopardizing their medical licenses. The group has urged state medical boards to change the language in mental health questions so as not to dwell on the past but focus on conditions affecting a doctor’s ability to do her job.

The NBA, in response to players such as Kevin Love and DeMar DeRozan opening up about their struggles with anxiety and depression, bolstered its mental health offerings, requiring teams to have a licensed mental health worker available for players in the 2019-20 season. NBA Commissioner Adam Silver said Love’s and DeRozan’s outspokenness helped inspire others. “Because there’s been more talk around mental health in the league,” Silver said at a Time magazine health-care conference in October, players “in a one-on-one setting will say, ‘Yeah, I have issues, I feel very isolated.’ ”

For ordinary workers, the best hope is that business leaders will force insurers to improve coverage. After his son was diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1990, Garen Staglin, a venture capitalist, and his wife began a fundraising effort that’s now amassed more than $450 million for mental health charities and research. Staglin has also started a nonprofit, One Mind, that among other things allows employers to compare their mental health benefits with those of other companies. He meets with CEOs and tries to persuade them to sign a pledge promising to reduce the stigma associated with mental health issues in the workplace and improve suicide prevention efforts. So far, companies representing 3.5 million U.S. workers have signed. That’s out of a workforce of 164 million. “We’ve got a long way to go here,” Staglin says. “We’re determined. I think the momentum is building.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Eric Gelman at egelman3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.