The Human Cost of Cheap Meat Gets Higher in the Pandemic

The Human Cost of Cheap Meat Gets Higher in the Pandemic

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It looks like bad times for Big Meat. The meat processing industry was slow to recognize the danger of Covid-19: Workers continued to work elbow-to-elbow and without masks long after other Americans took precautions. Outbreaks of the disease among employees have now forced the shutdown or slowdown of dozens of plants that produce beef, pork, and chicken. Tyson Foods Inc. Chairman John Tyson has placed full-page ads saying “the food supply chain is breaking.” The world is dismayed by scenes of farmers euthanizing hogs and chickens that can’t be sold—even as meat prices are leaping and supermarket shelves are emptying.

But it’s not all bad for Tyson and the other companies that dominate U.S. meat production, including Cargill, Brazilian-owned JBS USA Holdings, and China’s WH Group, owner of Smithfield Foods. The profits from the plants that continue to operate at full capacity have soared: Spot prices for beef and pork are way up because the supply is tight, while the price the plants pay for animals is down because the processors can’t handle all of them.

Meanwhile, President Trump’s invocation of the Defense Production Act to ensure no disruption in the U.S. meat supply effectively gives producers the government’s support in any lawsuits over workers’ exposure to the coronavirus, as long as the companies follow safety standards prescribed by government agencies. On April 28, Trump directed Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue to “ensure that meat and poultry processors continue operations consistent with the guidance for their operations jointly issued by the CDC and OSHA”—that is, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Labor unions and public-health advocates have accused Tyson and others of putting profit ahead of worker safety by keeping plants operating despite Covid-19 infections. But with Trump citing national security, “it’s easier for companies to say ‘we’re just following orders,’ ” says Jennifer Bartashus, a senior industry analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. “It is a really good time for those that can operate, even if they’re not operating at full capacity.”

The whole world is feeling the effects of the pandemic on the food supply. In India, starvation looms because a nationwide 40-day lockdown to stop the virus has deprived the poor of money to buy food. A program of free food, fuel, and cash transfers for the poor amounting to less than 1% of the country’s gross domestic product has proved insufficient. In Nigeria, stay-at-home orders from state governments have sparked panic buying. In Brazil, coffee growers worry they can’t keep their employees safe, and, in Honduras, a fruit export giant has been accused of downplaying the risks. Adding to the pressure, Kazakhstan, Russia, Vietnam, and other countries are moving to secure domestic supply by restricting exports that the world depends on.

The common thread around the world is that agricultural and food-processing workers aren’t treated like the essential workers they really are. They earn low pay and have crowded, dangerous working conditions. In wealthy nations, many of them are undocumented immigrants who are afraid to complain. Companies take advantage of that. “Because these giant multinational corporations didn’t make the investment to protect workers, their plants are being forced to close,” says David Michaels, a George Washington University public health professor who ran OSHA under President Obama.

To keep its production lines moving amid the spreading pandemic, Tyson Foods is offering a $500 bonus in May and another $500 in July to workers who maintain good attendance. People are still eligible for the attendance bonuses if they stay home because they have Covid-19, but some workers who aren’t sure they’re sick enough to qualify may decide to come to work anyway. Tyson spokesman Gary Mickelson said on April 29 that the company has made its relaxed attendance policy clear to employees. He also said the company is checking workers’ temperatures daily and taking other precautions, including placing clear plastic partitions between workers where it’s not possible for them to stand 6 feet apart. It began requiring workers to wear masks on April 15.

It’s no wonder that some meatpacking plants have become centers of infection in states like Iowa and Nebraska that have otherwise been lightly touched by the coronavirus. Social distancing is impossible when production lines are running at full speed. It takes a full complement of workers side by side to handle all the meat. It’s so noisy that workers, supervisors, and USDA inspectors have to shout into each other’s ears to be heard. The obvious solution is to slow down the lines and put workers farther apart, but that hurts profitability and reduces supply for groceries.

Some food processors are treating any Covid-19-related slowdown as more of a speed bump than a reason to permanently change how they operate. They’re continuing a long-standing campaign for permission to speed up production lines. Between March 31 and April 17, the USDA granted waivers allowing 16 poultry plants to operate at 175 birds per minute, up from 140, contingent on having enough workers to operate them. “It’s just absolutely astonishing to me that they’re having a hard time keeping plants open, yet they’re approving line speedups,” says Tony Corbo, a senior government-affairs representative for Food & Water Watch. Corbo says speedups increase the risk that workers will lose fingers, and that diseased animals will get past inspectors.

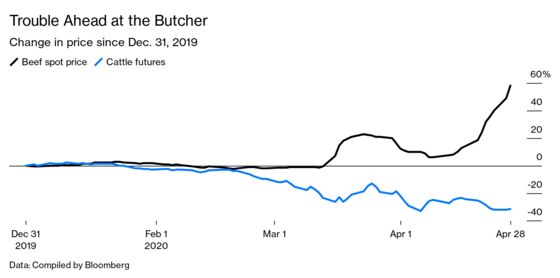

It’s not just advocates for workers and food safety who are angry at the meatpackers. It’s farmers and ranchers. On April 8 the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association wrote to Trump asking for an expanded investigation into the “striking disparity” between the low prices paid for cattle and hogs and the high prices packers receive for their output. The USDA had been investigating price disparities following a fire at a large packing plant last August in Holcomb, Kan., knocked out 6% of U.S. cattle-processing capacity, lowering demand for cattle. It’s since added the Covid-19 shutdowns to its investigation.

The pandemic has knocked out much more processing capacity than the Holcomb fire, with a commensurately bigger impact on prices. HedgersEdge LLC, a risk-management and market-research firm in Greenwood Village, Colo., calculates a profit margin for beef and pork packers based on the difference between their inputs (animals) and outputs (cuts of meat). Since 2014 the profit margin for beef has averaged $74 a head. On April 27 it reached $726, a record. The increase for pork is smaller, from an average of $24 a head to a recent level of $76 a head. Andy Gottschalk, the owner of HedgersEdge, says the indexes overstate the profits that packing plants can make because they’re based on the latest spot prices, whereas four-fifths of the sales volume is based on contracts that were set when prices were much lower. Plus, he says, the companies still have big fixed carrying costs for plants that are closed or operating below capacity.

But that doesn’t assuage the cattle ranchers and hog farmers. Republican senators who have clout in Washington have added their voices to the call for a probe by the USDA, including Steve Daines of Montana, Deb Fischer of Nebraska, Chuck Grassley of Iowa, Mike Rounds of South Dakota, and Kevin Cramer and John Hoeven of North Dakota.

The plant shutdowns and political backlash haven’t done much harm to processors’ stock prices. As the coronavirus spread, Tyson’s shares plunged along with the overall stock market; investors were worried about the closure of restaurants and other food-service establishments that were major customers. But even with plants shutting down, Tyson’s stock has rebounded 42% from its March low—not what you’d expect of a company fighting a lung disease that’s spreading through its workforce. Hormel is up 17% from its March low; Pilgrim’s Pride, 37%; and Conagra, 43%.

The industry has become dominated by a handful of giant companies, led by Tyson, the largest meat processor in North America. The top four companies in beef control 80% of the nation’s beef supply; the biggest four in pork control 60% of the pork supply; and the largest five in chicken control 60% of the chicken supply. For efficiency the companies have concentrated production in large plants that run multiple shifts, in some cases around the clock. The plants tend to be in rural areas where workers have few other employment options. The sheer size of the facilities makes them vulnerable to viral outbreaks, simply because there are more people to infect in a big operation than in a small one. The closure of just a few plants can have a significant effect on the nation’s food supply. Hence Trump’s executive order.

Conditions for workers in Big Meat have improved somewhat in recent years, thanks to outside pressure and the low national unemployment rate, which has forced employers to treat employees better to keep them from taking other jobs. Companies were shamed out of practices such as denying bathroom breaks, which had led some workers to wear diapers on the job, says Celeste Monforton, a lecturer in public health at Texas State University. Tyson has raised wages and is helping workers get their high school equivalency diplomas and citizenship. In Schuyler, Neb., Cargill Inc. is working with the governor’s office to secure funding for affordable housing. In other areas, it’s set up local clinics to provide free medical services.

But working in a meat-processing plant remains grueling and hazardous. And now, with Covid-19, it’s downright scary. “Inevitably, these large businesses create the breeding grounds for disease,” Representative Mark Pocan, a Democrat from Wisconsin, wrote in an April 29 statement to Bloomberg Businessweek. He’s the lead House sponsor of a bill calling for a moratorium on mergers in food and agriculture. Senator Cory Booker, the New Jersey Democrat who ran for president this year, is his counterpart in the Senate. Wrote Pocan: “Monopolies will always expose their weaknesses in times of crisis, and we’re seeing it in every industry.”

Covid-19’s rampage through the meat-processing industry—spreading disease in rural America while wreaking havoc on the meat supply—reminds us of a fundamental truth: How we treat the most vulnerable sooner or later affects the rest of us. —With Michael Hirtzer and Deena Shanker

Read more: What If Essential Workers Staged a Mass Coronavirus Strike

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.