Markets That Priced in a Trade Skirmish Now Brace for a Bruising Fight

Markets That Priced in a Trade Skirmish Now Brace for a Bruising Fight

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Wall Street’s pundit class sprung dutifully into action as the tariff fight between the U.S. and China suddenly escalated this month, dashing off pages upon pages of investment advice peppered with metaphors and anecdotes intended to help clients wrap their heads—and their portfolios—around the new state of play of the global economy.

For three analysts from Jefferies, this meant unleashing the 1970s earworm Suicide Is Painless in a note to clients. The theme song for M*A*S*H, the movie turned sitcom about wisecracking American doctors in the Korean War, had found its way into the analysts’ heads after the People’s Daily and other Chinese state-run media ran a commentary piece that evoked comparisons to the simultaneous peace talks and battles between U.S. and Chinese-backed forces during that conflict. The unsigned article was headlined, “If You Want to Talk, We Can Talk. If You Want to Fight, We Will Fight.”

What type of trade war the U.S. declared on China has been the topic of much debate ever since negotiations to resolve the standoff started in the spring of 2018. Would it be short and with limited casualties like the Falklands War? Or longer and bloodier like the Korean conflict? Stock markets got off to a roaring start this year as a consensus grew that this was a short spat that would be resolved quickly. But that hope has been shredded as tit-for-tat escalation in tariffs is causing a massive repricing in equity, bond, currency, and commodity markets.

The current consensus now is … well, there really isn’t one. But the idea that this fight could drag on much longer—and start doing more serious damage to global economies and markets—can no longer be dismissed. “We believe that the market is probably underestimating how long this will take to resolve,” says Charles Tan, co-chief investment officer of global fixed income at American Century Investment Management Inc.

In this trade war, it’s time to consider the possibility that China is digging in. Tan points to an assortment of events this year that could stoke nationalistic pride and harden the country’s stance, impeding progress toward an armistice: the centennial of the May 4 Movement, an uprising against Western colonialism; the 70th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese navy; and the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests. “It’s a very politically sensitive year for them,” Tan says. “So you have a lot of significance for China to show political solidarity and to be able to stand up against the Western powers.”

The ratcheted-up tariffs have caused economists to take erasers to their forecasts, but so far they’re not predicting a recession or other economic doomsday. Most say the latest round of duties and counterlevies will pare 0.1 percentage point to 0.3 percentage point off U.S. growth by 2020. In the event of a full-blown trade war, the International Monetary Fund estimates the hit could be as much as 0.6 percentage point in the U.S. and 1.5 percentage points in China.

The escalation has the potential to either cause higher prices for U.S. consumers or damage profit margins at companies that trade with China—or a combination of the two. The original 10% levies on $200 billion in Chinese imports likely did raise costs for some goods sold in the U.S., but price pressures elsewhere were so mild that it didn’t move the needle on inflation indexes.

It’s a different story now that the U.S. has increased those tariffs to 25% and is exploring levies of up to 25% on an additional $300 billion worth of goods. “If companies can’t pass on those higher costs, then margins are going to get squeezed, and that’s going to flow through and put more pressure on the equity market,” says Jack McIntyre, portfolio manager at Brandywine Global Investment Management LLC.

Other knock-on effects—such as damage to consumer and business confidence and widespread uncertainty that stymies investment—are harder to quantify. The escalation in hostilities is happening at a time when U.S. growth already waspoised to slow from a strong 3.2% reading in the first quarter. That quarter did get a boost from the U.S.-China trade tensions but not in a sustainable way. In the final three months of 2018, producers rushed goods and raw materials into the U.S. and stockpiled supplies in anticipation of higher duties. The effect of bringing forward those purchases was to lower imports in the first quarter, which shrank the trade deficit and boosted gross domestic product. Companies continued to build inventories in the first quarter—but those swollen stockpiles threaten to become a drag on growth, according to economists at Bloomberg Intelligence.

The Institute for Supply Management index of manufacturing activity fell in April to the lowest level of Donald Trump’s presidency, while the ISM reading for service industries was the lowest since August 2017. Both gauges are still in growth mode but inching closer to levels that signal economic contraction.

There is also the question of what other bad news may happen. With China running out of imports from the U.S. to match tariffs dollar-for-dollar, speculation abounds about other ways Beijing could push back. Modes of retaliation could include boycotting U.S. products, delaying customs inspections, or increasing regulatory scrutiny of American companies doing business in China.

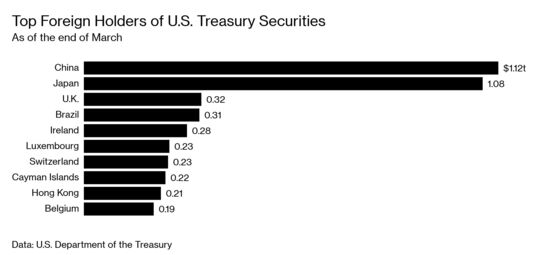

Two levers in financial markets are also being watched carefully: China’s holdings of U.S. government bonds and the daily fixing of its currency. With $1.1 trillion of U.S. Treasuries in its portfolio, China could theoretically cause chaos in financial markets—in the form of higher interest rates—by dumping U.S. government debt at a time when investors are being inundated with auctions of new bonds to finance a deficit swollen by tax cuts.

It’s an alarming prospect, but many bond market participants say it would be foolish to attempt because the impact wouldn’t be worth the damage to China’s ambitions as a global financial powerhouse. Even if a fire sale of Treasuries by China were to cause U.S. borrowing costs to surge initially, the Federal Reserve could cut interest rates and restart its bond-buying program to bring rates back down. And the seemingly limitless global appetite for U.S. debt goes far beyond China—ensuring yields remain close to historic lows despite a borrowing spree that’s pushed bond issuance north of $1 trillion annually. “The dumping of U.S. Treasuries is likely well down the list of China’s retaliatory measures, that comes after all tariff increases across all goods have been exhausted,” Deutsche Bank AG currency strategist Alan Ruskin wrote on May 13. There aren’t many other places for China to invest its reserves, he said, and an exodus from U.S. securities would “be disruptive for all markets inclusive of China’s own reserve assets and even more important its own asset markets.”

Devaluing the yuan to make Chinese exports more competitive might be another retaliation option for Beijing, though it also comes with risks. While the yuan has dropped by more than 2% vs. the dollar since Trump launched his latest tariff salvo, currency traders believe China has actively prevented a more pronounced slide for fear of invoking the wrath of Trump, who’s frequently accused the country of manipulating its currency.

What’s more, devaluation isn’t as powerful of a tool as it once was because China’s trade surplus has narrowed significantly as a share of GDP in the last decade. And, according to Bloomberg Intelligence economists, close to 20% of the value added in its exports comes from imported parts, which get more expensive as the yuan weakens.

Regardless of whether or how China fights back, investors are gravitating to the idea that there’s no guarantee Beijing will blink first. After all, there are less than 18 months until the next U.S. presidential election, and Trump has made a strong economy, a buoyant stock market, and his skill as a dealmaker the pillars of his sales pitch for a second term. “From a tariff standpoint, China gets hurt more than the U.S., but from a time standpoint I think the U.S. is more disadvantaged than China because we have short election cycles,” says Brandywine’s McIntyre. “China can ride this out.”

So will Trump blink instead? Perhaps, but that may not be before investors endure a whole lot more pain. Equities need to drop at least 10% for Trump to talk up prospects of reaching a deal with China when he meets with President Xi Jinping at the Group of 20 meetings at the end of June, according to Raymond James policy analyst Ed Mills.

Similar guesses are being made across Wall Street. Using options market jargon, investors talk about a “Trump put.” A put contract allows the holder to sell at a certain price, limiting potential losses. When stocks fall below that price, the put is “in the money.” So the theory is that if stocks fall too far too fast, Trump will suddenly strike a deal with China or do something else to juice the market.

Not everyone buys that theory. “I don’t think the president has a put,” says David Lafferty, chief market strategist at Natixis Investment Managers SA in Boston. “And if he does, it’s a pretty far out-of-the-money put.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.