Making Marines Into MacGyvers

Making Marines Into MacGyvers

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- At a desk in a trailer along a fence behind a garage, America’s future war fighters are squinting at widgets. If not for the camouflage uniforms, they could be watchmakers, these eight Marines, age 20 to 25, all grasping digital calipers and taking precise measurements of tiny things to put those measurements into a computer-assisted design program and build a 3D model that will be printed in plastic. When the day began, only a few of these men had ever worked in CAD or touched a 3D printer, and now they have only one hour to make a functional multitool.

“The best tool will go on the Wall of Fame,” says Brad Halsey, a tall, exceptionally cheerful man in khakis and sneakers. “The worst tool will also go on the Wall of … Shame? No, failure isn’t shame. It’s just another tool. We’ll call it the Island of Misfit Toys.”

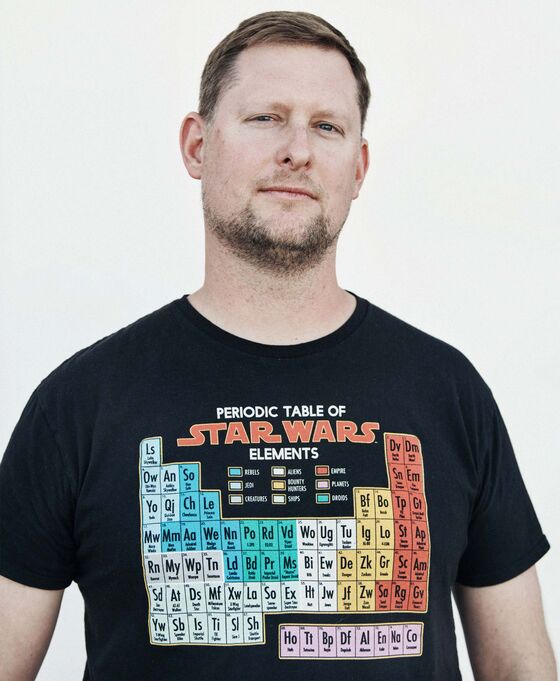

Halsey is the lead instructor of this program, Innovation Boot Camp, as well as co-founder and chief executive officer of Building Momentum LLC, a startup in Alexandria, Va., that trains people to leverage certain democratized technology—such things as CAD, 3D printing, laser cutting, and microcontrollers—to solve problems. That could be academics who’d like to be more practical, engineers who make elaborate designs but rely on techs to actually prototype them, or 20-year-old Marines who could use these things to be more effective on base and in combat.

Innovation Boot Camp is just one program, the Monday-through-Friday starter kit, under a larger project known as Marine Maker, which aims to infuse the basic skills and ethos of rapid prototyping throughout the Corps. Halsey says some of his earliest Marines nicknamed the program “MacGyver Camp,” after the inventive 1980s TV character who could fashion a bomb out of chewing gum and safety pins, and he was flattered. “He’s a hero of mine,” Halsey says.

The students in this class at California’s Camp Pendleton, chosen from various units within the 1st Marine Logistics Group, are technically minded. These are truck mechanics, radio repairmen, and ground electronics techs. You can imagine why the ability to rapidly design and print a mortar-tube bolt or a Humvee door handle would be useful to them when the alternative is waiting for a replacement part from the supply chain. But previous groups have come from infantry, combat camera, and even the vaunted Marine Raiders special operations unit. That was always the idea, Halsey says. The “door kickers,” the front-line fighters, need the skills every bit as much as the guys who fix their gear. “Innovation takes place at the intersection of urgency and necessity,” Halsey says. “Marines basically live at that intersection.”

And so do the bad guys in today’s asymmetric wars. “The enemy is using Amazon Prime to beat us,” he says. “They’re getting parts literally from RadioShack. We need to be fighting them in a more agile way.”

Building Momentum began in 2015 in Halsey’s basement and now uses every bit of a 20,000-square-foot warehouse. The inspiration goes back further, however, to the days after Halsey left the U.S. Navy (he received a medical discharge in 2001) and was working on defense and security projects for SRI International. He oversaw $30 million in mostly classified contracts, and the work was interesting but not entirely satisfying. Modern warfare is less about big weapons systems; today’s enemy fights on a much scrappier level. Halsey felt strongly that scientists like him could help soldiers react quickly to new problems. “I was a think-tank geek, frustrated with Death Stars and lightsabers that couldn’t affect the battlefield,” he says. “I decided to go to the war zone and make solutions as a nerd.”

Specifically, Halsey served under contract for a tech consulting firm called Exponent as what he calls an “embedded geek” for the U.S. Army’s Rapid Equipping Force. He spent almost a year on the ground in Iraq making tools out of military gear combined with things sourced from junkyards. He once ordered a bunch of mylar advertising balloons (the kind that fly over car dealerships offering great deals on Hyundai Sonatas), kitted them out with fake sensors, and launched them into the air to confuse militants who were targeting actual surveillance balloons.

When he got home, Exponent put him in charge of hiring and preparing more scientists for the Rapid Equipping Force. This was an eye-opener. “I found that most Ph.D.s at Stanford and MIT don’t like to operate outside their comfort zones,” he says. They’re very good at their particular specialties but not so good at execution—at translating ideas into things. Halsey created a Hell Week to weed out the scientists and engineers who couldn’t actually contribute in theater and eventually realized there was a business in this. Thus began Building Momentum.

The Marines, he says, “stumbled on us” when he met a brigadier general at a technology incubator that Building Momentum has since swallowed. That general told his superior about Halsey, and soon after, Lieutenant General Michael Dana, deputy commandant for installations and logistics, showed up in full dress blues for a tour. The general liked what he saw and told Halsey that he wanted Building Momentum to bring this sort of teaching to the Corps.

“It aligned really well with the culture that we empower our Marines with, which is to basically hack and modify and make the mission achievable in any way possible,” says Captain Chris Wood, who works under Dana in an office called Next Generation Logistics, or NexLog, which was set up to study and apply new tech to improve Marine logistics. Wood is of the opinion that a latent MacGyver lurks inside many Marines. “Now we can start to unearth and empower that, using these new technologies and the training to create much more well-rounded and capable individuals,” he says.

Marine Maker was officially born in 2016, under NexLog. The initial $4 million contract was supposed to last three years, but demand has been so high that the money is likely to be gone by the end of Year 2. Halsey is talking with the Corps about other possible courses, including programs tailored to particular problems—explosive ordnance disposal (EOD), for instance, or antidrone warfare.

Since the first MacGyver Camp at Pendleton in January 2017, almost 200 Marines have gone through the program in California, North Carolina, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. In December, Halsey took a container of gear to Kuwait and did his first camp for deployed Marines. The students from a crisis response unit built and installed a solar-powered surveillance system for ammunition supply points in one day and a GPS tracking system for cars in two. Typically, a unit would need to go through the bureaucratic channels for special gear, and when that special gear is spooky (in the CIA sense) there’s an even greater tangle of red tape to trip over. Now, in Kuwait, they can just ask the maintenance techs to whip something together.

When Halsey worked for the Army, he helped design a mobile lab built in a shipping container. The next step, he says, is to build smaller, even more portable labs that can be taken to forward operating bases deep in the field. Mission-specific kits with motors and microcontrollers and soldering sets could be carried in backpacks. There are so many potential uses, he says, starting with “little parts that break” on guns, sights, tools, and vehicles. Or maybe you want to put a sensor by a house, but you need to hide it, so you 3D-print a rock that looks like the local terrain. Dana’s directive, Halsey says, is clear—“to put these tools into the hands of the forward war fighter.”

On a Wednesday of Innovation Boot Camp, two men pop by the class. Even tucked away in a remote corner of the base, the trailer is a curiosity. Throughout the week, guests appear unannounced to sniff around, and that’s the case with these two.

The one who speaks the most is a towering chief warrant officer from EOD—the bomb squad—who had to duck to get through the door. He asks basic questions about the program and then some more specific ones about sensors and microcontrollers and the like.

“These tools are available; they’re cheap,” Halsey says. Today’s adversaries are often broke and poorly equipped, but they make up for that by being creative. No one is more aware of that than the bomb squad. “Their iteration cycle is fast,” Halsey says and laughs when someone points out that part of that process is a willingness to blow themselves up. “How do we approximate that?”—the iteration cycle, he means, not the self-immolation. “That’s the idea here.”

The officer nods. Marine EOD guys have great robots, but there’s always room for improvement. He can imagine quick fabrication of replacement parts. “It sounds like we could make controllers for the robots to go and hit something with a stick,” he adds.

An EOD-specific camp would be great, the Marine says, but making that happen is certain to be a process. In the meantime, he says, “I’d have immediate interest in sending a few of our geniuses to this program.”

Later that day, after the EOD guys have gone back to their robots, Halsey turns his thoughts to drones. A few weeks before the camp, insurgents in Syria used a drone swarm to attack a Russian airbase and, according to some reports, damage or destroy several fighter planes. “I hate to say it, but that’s a perfect advertisement for our business,” he says.

Drones pose several challenges. They’re hard to see. They don’t show up on radar. They’re quiet. And even if you do spot them, buzzing in low toward a base and your beautiful F-15s, how do you shoot them down? That’s going to require fast response and extremely accurate fire, probably in the dark. Halsey has thought about T-shirt cannons and net guns. A promising idea, he thinks, is to load a T-shirt cannon with twist ties—a cloud of shiny, pliable metal that should wreak havoc on small, delicate rotors. “But I want these guys to try it,” he says, looking around at a trailer of enlisted Marines soldering circuits on a motherboard. “They’re the ones getting blown up.”

That afternoon, a white sedan with “Government Vehicle” on the side rolls up and delivers the regiment’s commanding officer, Colonel Jaime Collazo, and his top aide, a master sergeant. Collazo oversees Combat Logistics Regiment 13, which includes the Ordnance Maintenance Company, as well as all the other units that fed Marines into the week’s camp; his mission is to ensure that deployed Marines get the parts and supplies they need as quickly as possible. He asks Halsey to describe exactly what he’s doing here, then stands upright, as stiff as a flagpole, while digesting the information.

“This is powerful stuff,” Collazo says. Several of his units have already begun to use 3D printers for replacement parts on trucks. In one case, technicians printed a metal rotor for an M1 Abrams tank motor that held up over hours of tests. “This thing, it is the future,” the colonel says. “It is how you really revolutionize and give us options that would not be present in the current evolutionary environment—or that aren’t available in the supply chain.”

“What items?” Halsey asks.

“All the items,” Collazo replies.

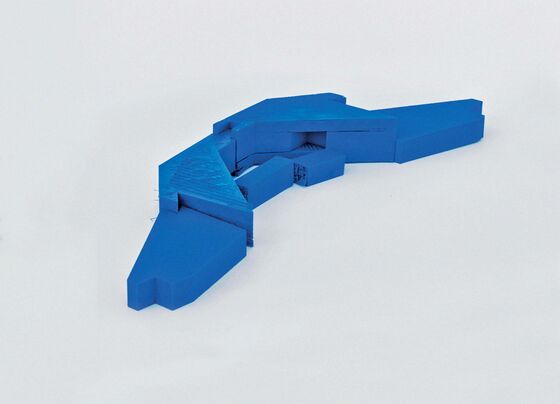

Innovation Boot Camp has a frenetic pace, by design. Halsey wants to show Marines that they can achieve basic working knowledge of a variety of technologies rapidly and use them in combination with a few core prototyping skills—for instance, welding and plasma cutting. They CAD and print a multitool; laser-cut pieces that assemble into a box without glue; cut and weld a strip of metal into a chalice that must hold water; and build a circuit to connect a battery to an LED light. Once they’ve covered a few skills and are no longer intimidated, if not yet proficient, they have to use them all in combination.

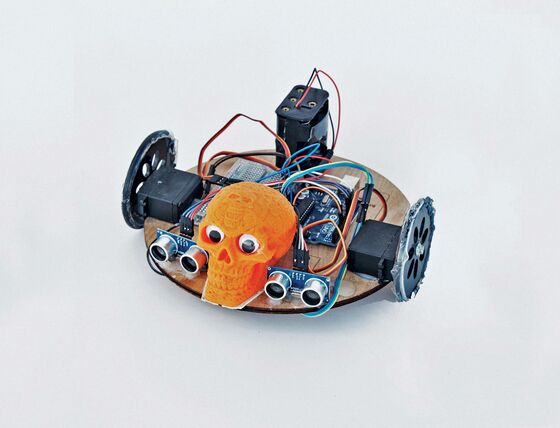

The Camp Pendleton Marines are given two hours to turn a pile of metal—mostly rounded and squared bars, plus casters and wheels—into a crude vehicle Halsey calls an “urban canoe.” It has to hold all four members of a team and must be powered and steered without hands or feet touching the ground. (They have to weld “paddles” for “rowing” across the lot—that is, pushing themselves along. It’s slow going even for the winning team.) Later, they’re given an afternoon and then the next morning to build a fighting robot out of wood, motherboards, and sensors.

Having done this program with both engineers and Marines, Halsey says he’d take the latter every time. “Engineers tend to overthink and execute poorly,” he says, citing a bridge-building challenge as evidence. At the end of Day 1, teams of two must quickly CAD and then print a bridge to span the chasm between two workbenches; the design can’t be too complicated or it won’t print in time. The team whose bridge holds the most weight is the winner. During one camp, Halsey stopped a team of engineers after they’d smugly sent their design to the printer and were preparing to leave for the night. He pointed at the estimated print time: 160 hours. “Marines do just enough and execute the hell out of it,” he says.

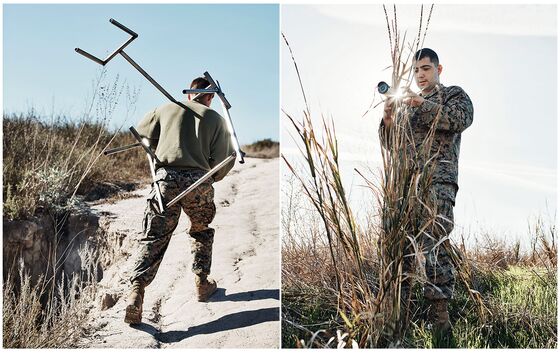

On Thursday afternoon, following the robot war, the Marines take on their final task of the week, which Halsey calls the Capstone Project. This is something he tends to script on the fly, factoring in the location and the abilities of the group. The idea is to force the Marines to use every skill they’ve learned over the week to address a real-world wartime scenario. In this case, the compound that housed the trailer is tucked against the base of some hills, and Halsey gives the group a two-part scenario. “Insurgents” are preparing an “attack” on the lab. By 9 p.m., the Marines need to create a sensor and surveillance network to monitor three locations inside the compound. When they return to the lab on Friday morning, the data those sensors will have captured should reveal clues that provide further intelligence on the upcoming ambush. Then they’ll have to react to the new information.

Halsey says the moments after the scenario brief can be overwhelming for the campers, who often sit in silence, hoping someone will take charge and assign jobs. To help them feel slightly less overwhelmed, he gives them an example from the movie The Martian, in which Matt Damon plays a man stranded on Mars with limited supplies.

“Matt Damon doesn’t freak out,” he says. “He doesn’t think, ‘How do I survive 500 days?’ It’s, ‘How do I survive three days? Where do I get water? How do I grow food?’ Break this out into digestible chunks.” He pauses for questions. There are none. “All right, go prevent attacks. Save America. We want you to feel like technology superheroes—to take this stuff you’re learning into the field.”

The lone sergeant, a mustachioed motor pool mechanic from Utah, takes charge and assigns duties based on whichever tasks guys feel most comfortable handling. They set up the quickie surveillance system and return on Friday morning to find footage that leads them to a hidden SD memory card containing details of the attack to come.

To counter, they have to go much bigger. The group will have to monitor and defend both the lab and a large water tank on a nearby hill, plus install surveillance gear on high ground to watch three different hilltops that could be used for mortar attacks. The enemy—Halsey, his two assistant trainers, and a couple of volunteer Marines—will try to “destroy” the tank and the lab. To win, the Marines have to spot the insurgents on camera, or via sensors, and call in fake mortar fire to take them out before any of them reach the lab.

Two Marines work on “grenades”—sensors that activate a car horn, telling an enemy that he’s been blown up—inside the shop. One of the sensors is a pressure plate made out of two cardboard squares separated by improvised cardboard hinges, which the Marine will bury in the dirt along a trail. Others write code and wire tiny motors to microcontrollers so their small cameras can pan across the landscape. “The hardest thing about placing sensors in the field is the batteries,” Halsey says, as he watches the men making homemade battery packs out of stacked AAAs. “I think half the rocks in Afghanistan are mine,” he says, meaning 3D-printed rocks filled with batteries, dropped from helicopters.

Later, the panning camera will catch him bounding toward a solar-power station the Marines built and installed on a stand they created in CAD and welded using metal from the urban canoes, which they first had to cut apart using plasma cutters. Henry Sullivan, one of the instructors, will step on the pressure plate, triggering the car horn, which startles him so badly that he screams, in his own estimation, “like a little girl.”

Halsey couldn’t be prouder: This is the first group to make a pressure plate. All week, he’s been dropping cultural references, most of them lost on these millennials. But one, 1984’s Red Dawn, seems especially apt. It’s the story of young American men who must repel a Russian invasion using only their hunting rifles and whatever they can build or steal. Halsey loves it. “If Red Dawn 2 ever happened,” he yells, “the nerds would rule!”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Daniel Ferrara

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.