The Fed Effort to Save Midsize Firms Isn’t Working, and Here’s Why

The Fed Effort to Save Midsize Firms Isn’t Working, and Here’s Why

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It sounded like a great idea back in April. With the economy getting hammered by Covid-19, the Federal Reserve hatched a bold plan to rescue thousands of midsize companies that were falling into a gap between government aid programs.

Using its magic printing press, the U.S. central bank would take $75 billion appropriated by Congress and turn it into as much as $600 billion in loans to companies damaged by the pandemic.

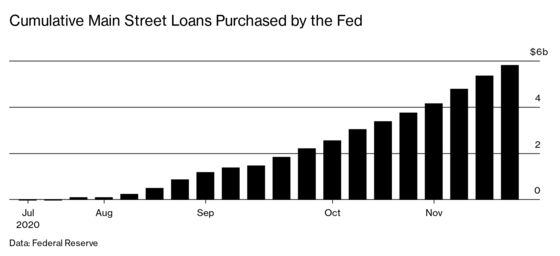

The effort now appears to have been doomed from the outset, squeezed between legal restrictions on the Fed’s emergency powers and the risk aversion of banks the program relied on to make loans. Eight months in, the Main Street Lending Program (MSLP) has pushed less than $6 billion out the door.

“There’s been bipartisan acknowledgment that Main Street isn’t working,” says Bharat Ramamurti, who sits on the congressional commission charged with supervising the spending authorized by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act. “I don’t think anybody is under the illusion this program is solving the problems that exist.”

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin announced on Nov. 19 that he wouldn’t approve an extension of the program, along with four other emergency lending facilities, past Dec. 31, but Democrats might be able to revive it. Some, including Virginia Senator Mark Warner, clearly want to.

“As we’re looking at the virus actually accelerating at this point, and the potential for businesses even going into more duress, the idea that we’d end the program arbitrarily on Dec. 31st—I just think makes no sense,” Warner says. “We think we need to make adjustments on both program eligibility, loans terms, and weight, so this works for more firms.”

It’s difficult to see how a few tweaks would suddenly resolve the real issues that afflict the program. These start with the limits on the Fed’s emergency powers. The central bank can lend almost infinite amounts of money, but it can’t give it away. That means it must reasonably expect repayment on loans and must charge rates that won’t end up undercutting private lenders.

The institution hasn’t run into those issues in the other programs it unfurled this spring to prevent capital markets from seizing as they did during the 2008 financial crisis.

The Fed used two facilities to buy up ultra-short-term securities from money market funds and from banks that act as market makers for all investors. It also lubricated longer-term credit markets by announcing it would buy corporate and municipal bonds. The central bank’s purchases amounted to tiny slivers of these vast markets, but its reassuring presence caused private investors to flood back in, knowing they wouldn’t get trapped with illiquid holdings if panic returned.

While the Fed was tending to the needs of larger companies, the Treasury Department was teeing up a rescue for small businesses. Despite a messy launch, the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) ended up ladling out about $525 billion in loans, most of which morphed into grants when borrowers used the funds to keep workers on their payroll and to pay bills.

Slipping between these safety nets was a whole layer of businesses—estimated to encompass 40% of the U.S. economy—that were too big for PPP and too small to access the bond market. So on April 9 the Fed unveiled a plan that looked like a win for everyone: Midsize companies would be thrown a lifeline, preserving jobs and helping to sustain the economy, and the Fed would show it cared about Main Street.

Vincent Reinhart, a former senior economist at the Fed, says the central bank took a lot of heat in the last crisis for going all-out to help big banks while appearing not to lift a finger for the average American. “It was Wall Street vs. Main Street, and going into this it was evident Jay Powell wasn’t going to make that mistake again,” says Reinhart, referring to the Fed chair. “I’m not saying it was insincere, but I am saying it was strategic, as well.”

Despite the good intentions, the MSLP’s effectiveness has been hampered by crucial design flaws. Unlike with its other emergency programs, the Fed must rely on banks to process the loans, as it lacks the capability to do its own underwriting. To come up with a set of terms that would entice lenders—as well as borrowers—to participate, Fed staff carried out extensive consultations with banks and companies. The upshot: Funds didn’t begin trickling out until July, almost three months after the first of the PPP money.

Since then, the Fed has continued to fiddle with the rules, and it’s lowered the minimum loan size, but the changes haven’t worked: As of Nov. 27, the program had purchased just $5.8 billion in loans from banks.

In a survey released in September, loan officers told the Fed that “overly restrictive” terms for borrowers and “unattractive” terms for lenders were preventing the program from taking off. When a company was deemed worthy of credit, banks preferred to make loans without the Fed’s participation, the respondents said. And when it wasn’t, the program’s terms didn’t do enough to make the loans palatable.

Under the terms of the program, the Fed buys 95% of each loan. That’s meant to reduce the risk for banks, but it doesn’t change the risk-to-reward calculus on each dollar lent. It merely turns a shaky $10 million loan into a shaky $500,000 loan. And if things go wrong, the $75 billion backstop provided by Congress protects only the Fed. It won’t absorb any losses suffered by the banks.

Some in Congress have urged the Fed to take on more risk. Indeed, the Fed could buy out 100% of every loan, leaving the banks to make their fees and move on. But the Fed wants lenders to have skin in the game to make sure their underwriting is reliable. Otherwise, the Fed might get saddled with too many bad loans, overwhelming the $75 billion backstop.

Alternatively, the Fed could ramp up the fees it pays lenders, or tweak the risk-to-reward weighting. It could agree to take 95% of any losses while leaving more than 5% of the potential profit. But that might prove politically perilous if it’s seen as being too generous to the banks. “There is a wide range of possible things you can do. They all may have some effective costs to taxpayers down the road,” said Eric Rosengren, president of the Boston Federal Reserve Bank, in an Oct. 8 interview. “There are some serious trade-offs if people wanted to make it a more attractive facility.” The Boston Fed is in charge of administering the program.

The incoming Biden administration might seek to revive the MSLP, though Republicans in Congress would probably block an attempt to reauthorize the $75 billion backstop. But Ramamurti, who was appointed to the oversight board by Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, is convinced that a whole new approach is needed, especially with the pandemic still raging and a widely available vaccine still many months away.

“For businesses in this category that are struggling right now, a loan is not going to be the right solution for most of them,” he says. “We need to provide direct support.”

Asked if Congress could have done more good by simply giving away $75 billion to midsize companies in March, Warner agreed. “With the benefit of hindsight? A smaller amount, straight grant program? Yeah.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.