A Luxury Home Firewall Could Save This Neighborhood From Amazon’s HQ2

A Luxury Home Firewall Could Save This Neighborhood From Amazon’s HQ2

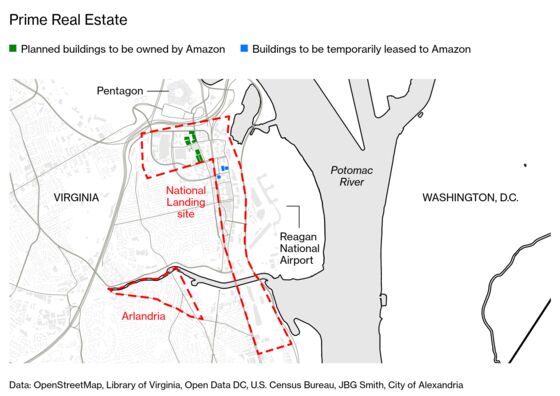

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Amazon’s development partner in the Crystal City section of Arlington, Va., has a solution to preserve affordable housing: surround the new headquarters with a firewall of luxury apartment towers. That way, the theory goes, the affluent won’t push into less-expensive enclaves nearby.

Two miles away, Sarah Ashton is already feeling the pressure to sell her 12-unit apartment building in the working-class Alexandria neighborhood of Arlandria. The offers keep coming, and Amazon.com Inc. hasn’t even arrived yet. But while she may get a windfall, she worries about her tenants, the Central American-born construction laborers, cleaners, and restaurant workers who populate “Chirilagua,” as locals call the community near Reagan National Airport. “When high-tech firms come, it stimulates inequality,” says Derek Hyra, a professor of public policy at American University in Washington and a former Alexandria city planning commissioner. “The lower-rent areas like Arlandria in close proximity face the biggest threat.”

Amazon’s selection of an area of Northern Virginia dubbed National Landing was celebrated by local leaders as a huge economic win. Now they’re preparing for the housing market fallout from the arrival of tens of thousands of tech workers earning an average of $150,000 each. JBG Smith Properties, which owns most of the commercial space in Crystal City, says the best way to prevent displacement is to give those new employees a wealth of choices suitable to their salaries. That means a protective wall of luxury apartments with dog-grooming stations and rooftop lounges. “If you build really close to the headquarters and in places that are already high-income, then there is less demand for investors to buy up older, garden-style apartments in Arlandria,” says Jenny Schuetz, a fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program.

JBG plans to construct 4,000 to 5,000 high-end rental units in and around Crystal City, says Executive Vice President Evan Regan-Levine. “One of the things we think we can do to minimize the impact is to build as much of the high-end as possible,” Regan-Levine says. “And add speed to getting that stuff done by streamlining approvals so these buildings can deliver in time for the people coming.”

One potential flaw: hipsters. One person’s luxury condo is another’s soulless box. Many young people aren’t interested in living in a community of high-rise condo towers like Crystal City, says Hyra, who studies gentrification. Many will end up in Arlandria and other nearby communities. “My feeling is that many of Amazon’s workers won’t choose to be directly in Crystal City, because of its sterile, corporate feel,” he says. Regan-Levine says Crystal City will be more attractive after the redevelopment, with trendy restaurants and coffee shops, as well as new parks.

In a statement, Amazon says it was drawn to the area in part because state and local governments had plans to address affordable housing, and that it planned to hire many people who already live there. The company also says new jobs in the region would come “gradually,” starting with about 400 expected in 2019.

The second part of JBG’s strategy to preserve the area’s last affordable units is a $150 million impact fund it’s raising. Investors would get a 7 percent return on their money, which would be loaned to nonprofit developers to purchase D.C.-area apartments at risk of being upgraded, says A.J. Jackson, the company's executive vice president for social impact investing. The developers would be required to keep the units affordable for at least 15 years.

Henver Palma, 54, and his family were among the refugees from El Salvador’s civil war in the 1980s to settle in Chirilagua. From his perch behind the counter, he scans his Super H barber shop—mirrors, faded photos of hair styles, green leather chairs, combs soaking in jars of alcohol—and sighs. The business he built with his wife over the past 15 years most likely won’t survive Amazon, he says. “It’s for low-income people,” Palma said. “A haircut is $15.”

He leaves the store and climbs up to Mount Vernon Avenue, lined in Chirilagua with businesses including a check-cashing shop, Salvadoran restaurant, and convenience store, and points left down the street toward neighboring Del Ray. That’s the future, he says. Less than a mile away, a hamburger at Holy Cow can cost $13, mixed-berry cobbler is on special for about $6 at the Dairy Godmother frozen-custard shop, and haircuts at Salon Bisoux (French for “kiss”) start at $48 for men and $93 for women. “This whole community will have to move,” Palma says.

It’s a Wednesday evening, and Evelin Urrutia, lead organizer at Tenants and Workers United in Chirilagua, knocks on doors of residents at Presidential Greens, a 396-unit brick apartment complex owned by UDR Inc., a large national apartment landlord. UDR did not respond to requests for comment.

A man dressed in baggy blue shorts answers one door. Clipboard in hand, Urrutia tells him in Spanish that Amazon is coming, and so are a lot of wealthy workers who will drive up rents. She’s conducting a survey and asks the man, a 46-year-old Honduran immigrant, about his housing costs. He says he’s already concerned about the cost of living in the area; working construction at commercial building sites, he earns $23,000 a year, though it’s hard to find work in the winter. He lives with two roommates, and the trio can barely afford the $1,500 a month rent, which climbs about $70 every year.

The future of such residents is what takes up most of Helen McIlvaine’s time these days. She’s Alexandria’s housing director, though she has a different description of her job: “I’m the girl with her finger in the dike.” Already, 90 percent of the market-rate apartments that were affordable in 2000 in Alexandria no longer are because of steady rent increases. McIlvaine says the city is committed to making sure Amazon benefits all residents, not just the ones most likely to get jobs there. That means protecting neighborhoods like Chirilagua and nearby Columbia Pike, she says.

There’s new money to help. The Virginia Housing Development Authority, a nonprofit created by the state, is kicking in an extra $15 million a year, for five years, for affordable housing in the Northern Virginia area. Alexandria has budgeted another $8 million a year. And if the city’s landlords want to redevelop their property, they’ll have a new incentive to keep rents affordable—at least for the number of apartments that currently exist on a site: In exchange they’ll be permitted to build three times as many higher-end units. Existing tenants would get priority for the affordable spots in new buildings, she says.

The neighborhood would change with a flood of wealthier residents, who can attract stores and restaurants for more expensive tastes. But the city will try to keep the community intact, McIlvaine says: “Yes, things are going to change, but this allows you to better shape what will happen. The city is going to have a planning process, and the goal is to make sure the character and diversity everybody loves is preserved.”

Ashton, the landlord who’s also a former mortgage banker and builder, says even if she doesn’t sell, she might be forced to raise rents. Amazon will likely drive up values, and that will lead to higher property taxes, she says. She likes Alexandria’s plan to allow more units for landlords who agree to preserve some affordable ones. And she thinks tax breaks for landlords who keep rents low might also work. “What incentive now do we have to keep this affordable?” Ashton asks rhetorically, as she points to some more expensive units that have crept onto a block of Chirilagua. “If someone gives us a pile of cash, why wouldn’t we take it?”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rob Urban at robprag@bloomberg.net, Pat Regnier

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.