Why Luxury Brands Will Keep Their Pandemic Playbooks

Why Luxury Brands Will Keep Their Pandemic Playbooks

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When the chief executive officer of Swiss luxury brand Bally looked at online revenue during the depths of the pandemic, he noticed something curious. Internet sales were robust in U.S. cities that hadn’t been on his radar. “These are cities that naturally a European brand will not think of first,” Nicolas Girotto says. “You will think about New York, Los Angeles, Miami. But there are big opportunities in Austin and Houston.”

Bally, known for its hand-crafted leather shoes, is looking at opening stores soon in Houston and Charlotte. The expansion is part of Girotto’s two-year plan to increase the number of stores Bally has in the U.S. to as many as 25, from 15, while also investing in its online platform.

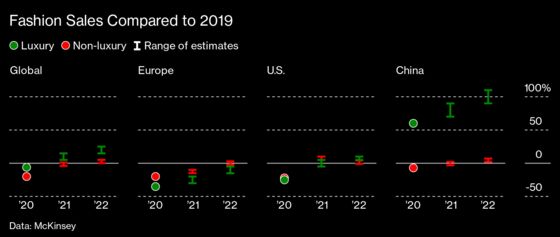

After surprisingly solid sales during the pandemic, European and U.S. luxury brands are feeling bullish heading into 2022. Sales of luxury goods are expected to grow as much as 25% next year compared with 2019, according to McKinsey & Co. That’s more than the flat to 5% increase the firm projects for the broader nonluxury fashion sector. While most of luxury’s expected expansion is powered by Chinese consumers, U.S. shoppers are also crucial.

The industry is noticing “the strength of luxury in the United States, where a few years ago people were only pointing at China and Asia as the growth trajectory,” John Idol, CEO of Versace and Jimmy Choo parent Capri Holdings Ltd., said recently.

To ensure that the sale of high-end handbags, watches, jewelry, and clothes in the U.S. accelerates in 2022, even as Americans deplete their stimulus payments and the extra savings they squirreled away during lockdowns, luxury company executives are putting into practice some of the lessons they learned during the depths of the pandemic.

One new development is that many Americans have become comfortable buying luxury goods online. Before Covid-19, executives at high-end brands had often treated their e-commerce operations as an afterthought. They saw brick-and-mortar shops as the best venue to display their brands’ artisanship and exclusivity, as well as the expertise of their staff. “Before the pandemic, many people thought consumers would not buy fine jewelry online,” Gina Drosos, CEO of Zales and Kay parent Signet Jewelers Ltd., says. “That is becoming more and more untrue.”

Online spending surged to 23% of luxury sales in 2020, from 12% in 2019, according to Wells Fargo analyst Ike Boruchow. He expects e-commerce to represent more than 30% of sales—or $140 billion—within the next five to 10 years. Much of that jump is luxury brands playing catch-up with the broader retail industry. Online sales for apparel and footwear, for instance, jumped to 35% to 40% in 2020, from 25% in 2019, according to a Wells Fargo report.

Such robust internet sales have exposed the shortcomings of some companies’ online businesses. Take luxury e-commerce platform Yoox Net-a-Porter, controlled by Swiss luxury group Richemont. Net-a-Porter operates via a wholesale model, buying items from luxe brands at a slight discount, then shipping them out from a few warehouses. When Covid shuttered some of those facilities for a time, Net-a-Porter couldn’t respond to online demand for luxury goods, and it’s been struggling to catch up. Competitor Farfetch Ltd., which gets most of its inventory from boutiques around the world and has a more effective technology and logistics infrastructure, fared better.

Now, Richemont is in talks with Farfetch about teaming up to use its technology and logistics platform, among other possibilities. Some analysts consider the discussions an acknowledgment by Richemont that if it can’t make Net-a-Porter profitable during a pandemic, it might never happen. “Luxury brands and luxury platforms have always been behind the eight ball with digital capabilities,” Boruchow, the Wells Fargo analyst, says. “Maybe it took Covid for a Richemont to realize that.”

Not everyone embraced digital sales during the pandemic. Chanel still doesn’t sell any of its handbags or clothes online. That’s a longtime strategy that analysts attribute in part to the French brand’s concerns about being unable to create an online shopping experience that’s as sumptuous as the one in its stores. There’s also the challenge of controlling purchases by resellers, who buy and then flip coveted luxury handbags.

Delving even further into the digital world, brands are selling virtual versions of their products so users can dress their online avatars on platforms such as Roblox. “Luxury brands need to start to test-and-learn in this space,” says Sarah Willersdorf, Boston Consulting Group’s global head of luxury. Brands should consider hiring someone to lead the latest digital developments—a “chief web 3.0 officer,” she adds.

In May, Gucci sold digital versions of its Dionysus bag on Roblox for the equivalent of around $4.75. Then, due to high demand, those digital items were resold on the platform for thousands of dollars—more than the price of the physical item. Ralph Lauren Corp. introduced a virtual clothing collection in August that offered users on the Zepeto platform 12 looks to buy for their online personalities. “Making our product available to purchase and wear digitally and allowing consumers to experience the brand in immersive new ways is the next frontier,” Ralph Lauren Chief Digital Officer Alice Delahunt said at the time.

Luxury executives are also finding different ways to reach customers offline. Many, like Girotto at Bally, are opening stores in new cities in the U.S. to ride out what they expect to be a prolonged lull in international tourism thanks to Covid. “The future of luxury is going to be much more domestic,” says Anita Balchandani, a partner at McKinsey.

For the past decade, high-end brands have generated a significant portion of their revenue from Chinese and other Asian travelers who bought expensive purses, scarves, and clothing on trips to Europe. When Covid shut borders, luxury executives feared their revenue would plummet. Instead, Chinese shoppers have started buying more at home in China. That’s been possible because brands have opened stores across the country in recent years and launched on Alibaba Group’s Tmall Luxury Pavilion, a sophisticated e-commerce site for high-end goods.

In Europe and the U.S., “because of the constant inflow of tourists, a lot of the brands were focusing on them and not necessarily really working at activating the local customers,” says Achim Berg, McKinsey’s global head of luxury.

Now brands in the U.S. are paying much more attention to places they had overlooked, particularly the Lone Star State. “Texas is absolutely on our radar,” says Charles Gorra, CEO of Rebag, which sells pre-owned luxury handbags. “It’s somewhere where we want to be offline in the near- to medium-term future,” he says, referring to potentially opening brick-and-mortar stores.

In August, Rebag opened a store in Greenwich, Conn., after Gorra realized clients who had moved there from New York City during the pandemic were staying put.

Over the summer, luxe store openings in nontraditional locales included Louis Vuitton in Plano, Texas, Hermès in Troy, Mich., and Christian Dior in Scottsdale, Ariz. These new stores in new cities are often smaller. When the pandemic hit, some luxury brands were left “holding on to these massive flagship locations on Madison Avenue and in Hudson Yards—and they were really just money pits,” says Justin Abrams, CEO of Flagship, a data and analytics platform that helps retailers identify new markets for their stores.

In the past year, Abrams has worked with French children’s clothing company Bonpoint as well as Bogner and Proenza Schouler to open stores around the U.S. that are about 1,500 square feet, which is smaller than many luxe brands would have considered before Covid started to spread.

The rise of e-commerce in the luxury world during the pandemic has facilitated those moves to smaller stores, Abrams says, because brands can use their stores to showcase some of their products and count on shoppers to check out other items online. “They used to need to house inventory, and now that’s just not the purpose,” he says.

Brands are increasingly renting space on shorter-term leases to test the new markets and store formats. Luxury companies have been eager to open stores because they need brick-and-mortar more than their general retail peers: Even with the surge in online shopping during the pandemic, many luxury shoppers continue to prefer to shop in person. “The luxury sector in particular had the most pressure to accelerate the return to physical retail,” Abrams says. “But they needed to do it in a smart way.”

The RealReal Inc., which sells pre-owned luxury apparel, has also been opening smaller stores in well-heeled neighborhoods. Its pre-Covid strategy of large flagship stores in city centers wasn’t working well during the pandemic because the number of women dropping by to consign their luxury goods fell, as many were working from home. The RealReal’s supply of items began to dip as online demand surged. The company opened 10 neighborhood stores during the pandemic, including in Brooklyn, N.Y.’s Cobble Hill and Larkspur in Marin County, Calif., north of San Francisco.

Read next: As Big Tech Eyes Smart Glasses, Luxottica Holds the Key to Success

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.