South America Votes Right While Leaning Left

Latin America Votes Right While Leaning Left

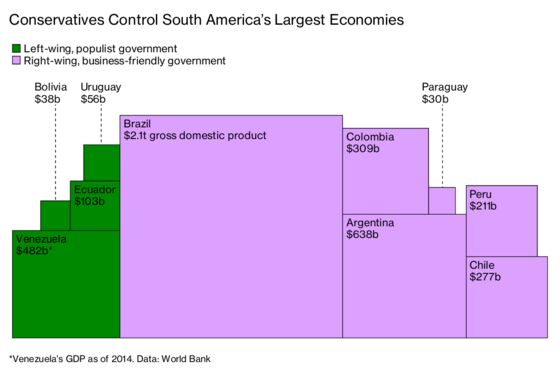

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- With the swearing-in of Jair Bolsonaro as Brazil’s president on New Year’s Day, right-leaning, market-friendly leaders will govern much of South America—in total, 85 percent of the continent’s 415 million citizens. Many of those people, however, still need a little convincing that right-leaning, market-friendly governments are the way to go.

Notionally at least, the rightward pivot among leaders means that for the first time in decades, most of South America’s collective $3.2 trillion economy is aligned with U.S. commercial and diplomatic interests. That could free billions in investment, merger activity, and trade partnerships. The challenge for those in power is reversing protectionist policies that rely heavily on government subsidies to support ailing industries, coupled with a continental workforce that’s fallen behind global standards.

In Colombia, Argentina, Chile, and Brazil, voters and institutions have stubbornly resisted change. None of the conservative leaders elected in the past three years took office with the absolute legislative majority needed to avoid a runoff or to form a clear governing bloc. Many pursued austerity policies upon entering office, but as the reality of those changes sunk in and the leaders’ approval ratings dwindled, their efforts to modernize economies, shore up public finances, and generate growth were slowed.

“The Right is in power, but it’s weak, often unpopular, and faces an unfavorable global scenario,” says Daniel Zovatto, Latin America director at the Stockholm-headquartered International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Throughout the region, public coffers are strained, and the prospects for emerging markets have soured amid rising U.S. interest rates and deepening trade wars. “Investors betting on magic formulas and quick solutions will be very disappointed,” he says.

Bolsonaro has promised to stanch bleeding in the public finances of the continent’s biggest economy, rein in a looming pension crisis, and sell off state companies. He’s vowed swift action to stop the omnipresent crime that constrains daily life and commerce. All that will take cooperation from lawmakers—but Bolsonaro has also reduced the number of cabinet-level posts traditionally doled out to rival parties as sweeteners. Members of congress, even some from his own party, have already commenced grousing.

Running for president of Colombia this year, Iván Duque modeled himself after Alvaro Uribe, who in the early and mid-2000s won two presidential elections in the first round. But Duque, a 42-year-old lawyer who has criticized the peace process between the Colombian government and a guerrilla army for being too soft on revolutionaries, was forced into a June runoff against a former member of the M-19 rebel group. His attempt to offset corporate tax cuts with levies on food backfired, tightening a budgetary noose that will likely prompt spending cuts. Now, three months after Duque took office, almost 3 out of 4 Colombians think their country is on the wrong track, according to polling firm Invamer.

In Argentina, President Mauricio Macri’s fast-rising star and pro-business agenda faded quickly. A controversial pension reform measure passed in December 2017 cost him dearly in political capital, and further attempts to slash labor costs by cutting severance pay and reduce pension outlays by raising the retirement age were put on the shelf. A currency crisis dragged the economy into a recession this year and pushed Macri’s approval rating to a record-low 33 percent. Poverty increased in the first half of 2018 for the first time since he took office in December 2015.

Chile provides perhaps the starkest example of an agenda unfulfilled. Sebastián Piñera was reelected as president in December 2017 with 54.6 percent of the vote. Nine months after being sworn in for a second time, he has yet to secure approval for any major bill, and his popularity is at an all-time low following the police killing of a young indigenous Mapuche in the Araucanía region in November. To look at the election result and think that the Right is dominant in Chile is “a deep mistake,” says Guillermo Holzmann, a political analyst and professor at Universidad de Valparaiso. “This government is not in power because of the Right or the Left—these are 20th century concepts—but because they appealed to the frustrations and the expectations of the small portion of voters that decide elections.”

Those voters remain frustrated. Many covet a first-world standard of living but remain resolutely resistant to free-market dogma. Chile pioneered orthodox, market-friendly policies in Latin America and, in 2004, became the region’s richest nation by per capita income. Yet even there, protests over inequality in education and income have forced policymakers to build out social welfare in recent years. Piñera promised to increase pension pay and improve health care. And pressure is growing on him to pledge to do more. “Piñera is at a turning point where he needs to address the issues around inequality,” Holzmann says. “If he doesn’t, Chile will descend into a scenario of higher social conflict, which can lead to the rise of the kind of populism that offers magical solutions that in practice don’t exist.”

Austerity is unpopular anywhere. But in a region with eight of the 20 countries ranked worst on the Gini index of income inequality, and where rising income inequality, resilient poverty, and chronically poor public services such as health and education are prevalent, it’s all the more difficult to slash fuel subsidies, deregulate labor markets, or cut pension benefits. Those who’ve tried to impose strict cuts have often found their opposition insurmountable. Today’s struggling rightists don’t have the cushion of a commodities boom that got leftists such as Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil or Argentina’s Néstor Kirchner reelected more than a decade ago. Mexico’s firebrand leftist Andrés Manuel López Obrador is the exception that proves the rule: Even after achieving a landslide victory, he proposed a restrained budget on Dec. 15 that does little to upend the priorities of his more conservative predecessor.

The region's citizens have consistently demanded that their governments put people before markets, says Miguel Kiguel, director of consulting firm EconViews in Buenos Aires. “Latin America is much more center-left than other parts of the world.” The people “want a protective government,” he says. “A government that basically takes responsibility, not for industry, but for a lot of services: education, health care, etc.”

Brazil shows signs of moderating despite Bolsonaro’s promises of radical change. Just before winning in October, the former army captain backtracked on some of his plans to sell strategic assets. Tough campaign talk on China, Brazil’s largest trading partner by far, has given way to a friendlier posture. A post-election rally by the real soon petered out amid questions over the incoming government’s capacity to implement reforms.

Bolsonaro appointed a group of pro-market University of Chicago-trained technocrats to cabinet and administration positions to pursue opening up the country’s notoriously closed economy. But having avoided a meaningful discussion of economic issues during the campaign, he doesn’t have a clear mandate to downsize Brazil’s costly and unwieldy social welfare state. Says Murillo de Aragão, head of Brasilia-based consulting firm Arko Advice, “If he can get done half of what he plans, that would be a success.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Stephen Merelman

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.