Lance Armstrong’s Podcast Is Making Cycling Fans Forget About the Doping

Lance Armstrong’s Podcast Is Making Cycling Fans Forget About the Doping

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The theme of last year’s Global Volatility Summit in New York was a carnival. Attendees at the annual conference, put on by the hedge fund Capstone Investment Advisors, were treated to talks and panels on quantitative investing and the impact of the trade war. There were diversions such as the “VIX Rollercoaster,” “the Wheel of Tax Misfortune,” and “Policy Skee Ball.” Also, Lance Armstrong showed up. “That last conversation was amazing,” the 47-year-old former cyclist said as he settled into a chair on the stage at Manhattan’s Chelsea Piers, referring to a six-person panel discussion on tail hedge strategies. “I understood everything.”

Self-deprecating humor doesn’t come easily to Armstrong. Perpetually stone-faced and quick to anger, he was known during his professional cycling career as a heroic survivor of late-stage testicular cancer who went on to win the Tour de France, cycling’s biggest event, a record seven times. He was also, of course, a cheater—the leader of a team that, according to the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, “ran the most sophisticated, professionalized, and successful doping program that sport has ever seen.” Armstrong disputes that his doping was unprecedented—it was part of a larger culture of doping in cycling, he’s long argued—but not that he cheated nor that he crossed ethical lines in his attempts to silence critics.

Former teammates turned on him, and he finally admitted to taking drugs in a 2013 interview with Oprah Winfrey. Armstrong was stripped of his cycling titles and dropped by Nike Inc., his longtime sponsor. His cancer foundation, Livestrong—which had worked with the apparel giant to turn yellow wristbands into a global virtue signal—cut ties with him. (The charity has continued to operate, but in a diminished, Lance-free form.) The U.S. Postal Service had sponsored Armstrong’s team during the glory years; in 2013 the federal government joined a fraud lawsuit against Armstrong and the U.S. Postal team manager, Johan Bruyneel, seeking to recover $100 million in damages.

In 2016, with the trial looming, Armstrong devised an ambitious plan to un-disgrace himself. Banned from professional cycling races, he created and started riding in his own unsanctioned cycling events. Unable to land a broadcasting gig, he started a podcast and covered the Tour de France himself. Dropped by the sponsors who’d paid him about $20 million a year to promote their wares—and then sued him for fraud—he began selling his own cycling gear under a new brand, Wedu.

Amazingly, given the depth of Armstrong’s disgrace, his plan seems to be working. His podcast, The Move, was near the top of Apple’s podcast charts during the Tour de France in July. It was No. 3 among sports shows as of July 19, just ahead of Bill Simmons’s show and all of ESPN’s podcasts.

A podcast might seem an unlikely vehicle for a business comeback, especially since Armstrong himself is an amateurish broadcaster, sometimes forgetting or badly mispronouncing the names of riders and French towns, sometimes going off on wild tangents. But it’s 2019, and podcasts are an increasingly influential medium, minting celebrities, capturing a growing share of the radio audience—about 90 million Americans listen to at least one each month, according to Edison Research—and sending listeners and advertising dollars to other platforms. Armstrong’s podcasts, like many popular radio shows these days, also appear in video form on YouTube, where they can attract hundreds of thousands of viewers. And they've also brought Armstrong back into the good graces of TV bookers: he commentated, albeit in an unpaid capacity, during NBC's Tour de France coverage this year.

In each of the past two years, The Move generated somewhere around $1 million in revenue during the three-week Tour de France through an advertising partnership with Patrón tequila and a half-dozen smaller sponsors.

Armstrong’s speaking requests are coming back, too, even if they’re a little outside his comfort zone. I’d been invited to the volatility conference in March 2018 by his longtime manager, Mark Higgins, who said it would give me a chance to see this new side of Lance. Onstage, with 300 or so finance types in striped shirts staring at him, he looked uneasy, and he became visibly irritated when the interviewer, Ryan Holiday, the author of Trust Me, I’m Lying and Ego Is the Enemy, asked him to give advice to finance professionals based on his past dealings with the government.

Armstrong grimaced, but he played along. If you’re guilty, he said, avoid emphatic denials. “If I’d just doped to win a bike race, like 200 other guys did in the same bike race, we wouldn’t be sitting here right now talking about this,” he said. “But those 199 other guys didn’t get up in front of the world and take everything on, and be litigious, and, to be honest, be a total prick.”

Armstrong’s final reckoning with his past behavior came the following month, when he and the U.S. government reached a $5 million settlement. The comparatively small size of the penalty was widely seen as a victory. Armstrong seems to agree. “They wanted a hundred,” he tells me. “And they left with five.”

With the lawsuit squarely in the rearview mirror, he announced he was starting a venture capital outfit, Next Ventures, which has raised about $25 million of a planned $75 million, according to a July Securities and Exchange Commission filing. Investments include a stake in Spar Technology Corp., which makes an iPhone app that allows users to compete in physical challenges against their friends for money, and PowerDot, a $200 “recovery and performance” device that stimulates muscles with electrical pulses. During the Tour, Armstrong has talked up both on his daily episodes of The Move. “Tim Ferris, Chris Sacca, Gary Vaynerchuk—they all do this,” he says, referring to the self-help author, the former Shark Tank star, and the social media guru, respectively. “Nobody does it specifically dedicated to this world—endurance, outdoors, health and fitness.”

We’re speaking in the sunroom of a modest bungalow in a slightly sketchy part of Austin, aka Wedu Sport’s headquarters. Armstrong is dressed casually—shorts, running shoes, white T-shirt—for a podcast taping with John Furner, chief executive officer of Sam’s Club. He recorded the episode in a shed behind the house that’s been retrofitted with soundproofing, audio equipment, and cameras for YouTube. It’s not much, considering Armstrong was once one of the best-paid athletes in the world, but he sees it as the beginning of something new—a sort of DIY Nike that will encompass media, events, and apparel. “It’s f---ing awesome,” he says of the popularity of his podcast. “It feels like all is not lost.”

“I don’t wanna lie: I don’t want to not talk about that,” Armstrong said, referring to the fraud trial, on a Wedu podcast called The Forward, which appeared in iTunes and other podcast apps in 2016. He acknowledged it could bankrupt him. “That’s a big deal for me and my family. But the goal is to get that part of life behind me and move forward. That’s the name of this thing.”

It was the day after Christmas, and Armstrong was in a reflective mood. At the time the crew consisted of Armstrong and Higgins. (Full time headcount at Wedu has since doubled, to four.) Most of the guests on the show so far had been Armstrong’s friends. The mix was eclectic: tennis great Chris Evert, historian Douglas Brinkley, musician Seal. Episodes were posted every few weeks, mostly recorded in Armstrong’s wine cellar, on a laptop. The show, he told his listeners, had attracted more than 1.5 million downloads in its first six months—a big enough audience to sell to advertisers, though Armstrong said he had no immediate plans to do so. “I don’t want you all to think that this is a money grab for me,” he said. “I know how people view my situation—the last four years of my life.”

Eventually though, he said, he hoped the podcast would generate revenue for Wedu. There would be events, media, and merch. And—in case anyone doubted that Armstrong was committed to reclaiming all of his old empire, which had merged his athletic prowess with his capacity for raising money for cancer patients—he hinted at a charity component. “Dear cancer community,” he said, his voice breaking slightly. “I want back in.”

During that 2016 Christmas episode, and in interviews since, Armstrong has presented his decision to launch a podcast as a spur-of-the-moment thing. Higgins had suggested the idea years earlier, but Armstrong resisted until June 2016, when, on a lark, he posted his first interview, a conversation with Tim League, a friend and the founder of Alamo Drafthouse Cinema LLC.

In reality, it was more considered. Armstrong tells me he’d wanted to find a way back into the business world for years but felt helpless. “Everybody exited: the backers, the sponsors, the partners, my foundation,” he says. “We were in this place for years where it was like, F---, we got nothing.”

Armstrong first began contemplating a comeback around 2015, when he contacted Strava, developer of the fitness app he was using to track his daily runs, after an overly aggressive fan used it to harass him. When he asked the company for help, Armstrong recalls that one of the company’s founders mentioned something else in passing: Armstrong had the biggest fan base of any Strava user. (Today he has more than 116,000 followers. Tejay van Garderen, the top American rider, who dropped from this year’s Tour after a crash during the seventh stage, has fewer than 25,000.) “I was running four miles a day,” Armstrong recalls thinking. “Why would you wanna watch that?”

But the real turning point came the following year, when a friend at a major sporting goods company covertly passed him an internal market-research study of bike customers. “It was like 3,000 respondents,” Armstrong recalls. “They asked about all kinds of random sh--. Do you ride a mountain bike or a road bike? How old are you? Where do you live?”

The survey also asked respondents to name their favorite professional cyclist, offering 10 choices, including Chris Froome, a four-time Tour de France winner widely regarded at the time as the world’s dominant road cyclist, and Greg LeMond, the legendary 1980s Tour winner. Armstrong was the overwhelming favorite, despite all the controversies. “It wasn’t even close,” he says. “The people are out there. But they don’t have a bike race they can attend, they don’t have a [jersey] they can buy.”

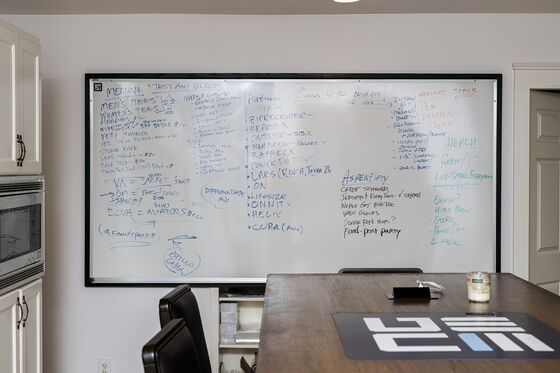

Armstrong set about rectifying that. He got in touch with an old collaborator, James Selman, formerly of the Portland, Ore., office of Wieden + Kennedy and a key designer behind Nike’s Armstrong ads. Armstrong and Selman had stayed in touch after the designer left the agency world to take a job at Apple Inc. Armstrong asked Selman, who’d started his own design studio, to work up an idea for a brand aimed at enthusiasts of outdoor endurance sports. Armstrong picks up a book Selman produced with Wedu’s logo and slogan on the cover—“Solidarity for the solitary”—and starts flipping through it. On each page there’s an inspiring photo and aphorism, which Armstrong reads off at a rapid clip. “Forward, never straight. Never take counsel from fear. It’s called Wedu, not ‘we don’t.’ ” Selman’s work, coupled with Armstrong’s discovery that he still had an audience of fans, gave him the confidence to start Wedu in May 2016. The sponsors, Armstrong told himself, “are not coming back. So I’ll just create my own thing.”

In 2017, with The Forward generating buzz, Armstrong began selling T-shirts and trucker hats featuring Selman’s design: a forward arrow with a crick in the middle. The logo eventually went on cycling kits, water bottles, hoodies, and high-end sunglasses, among other products. He also launched his second podcast, The Move, beginning with daily coverage of that year’s Tour de France. The episodes featured Armstrong and longtime Austin radio personality JB Hager. The crew eventually included Bruyneel and George Hincapie, a teammate who later turned accuser. “We went through a period where we didn’t talk much,” says Hincapie, who in addition to his podcast duties co-owns Hincapie Sportswear, an apparel company, and the cycling-themed Hotel Domestique in Travelers Rest, S.C. (In cycling, domestique, French for “servant,” refers to a lesser rider who fetches water bottles for the team leader.)

The same year, Armstrong and Higgins held two Wedu rides: the Aspen Fifty, near Armstrong’s Colorado summer home, and the Texas Hundred, held in the Hill Country north of Austin. The events, which cost participants about $200 each for the Aspen race and $100 for the Texas one, are proof that Armstrong still has committed fans. At last year’s Texas Hundred, some 500 riders showed up, including a Seattleite who rode a vintage U.S. Postal bike. After giving a short speech at the starting line, Armstrong rode alongside Hincapie, just like in the old days. After finishing, he changed out of his Wedu Lycra and mingled for an hour or so with the attendees, taking selfies and signing autographs, including one on the frame of the superfan’s bike. Before leaving, Armstrong noted the turnout—the race had attracted 70 more people than the previous year’s edition. “Moving in the right direction,” he said.

In addition to the event revenue, apparel sales, and advertising, Wedu makes money through an NPR-style membership program, where superfans pay $60 a year to get a T-shirt, some stickers, early access to gear, and special members-only podcasts. So far, Higgins says, thousands of people have signed up. It’s all modest for now, but as the brand gets better known—and as his moral failures fade into the past—he expects merchandise sales will improve. “We were very conservative on merchandise,” he says, referring to the modest selection and limited quantities Wedu sold initially. “We won’t be conservative again.”

Part of the appeal of Armstrong’s podcasts is that he’s strangely, unexpectedly vulnerable. During his career, he tended to treat press conferences like depositions and was prone to angry outbursts. (“You are not worth the chair that you are sitting on,” he once snapped at a British newspaper columnist.) While he was speaking at the Volatility Summit, 30 minutes or so after meeting me backstage, Armstrong gave me a somewhat awkward shout-out from the stage. “I hate the media, I’ll just be honest,” he said after mentioning me by name. (“I felt bad saying that,” he says later.)

Of course, now, in addition to hating the press, Armstrong is the press. He says he tries to avoid adopting any kind of adversarial position in interviews, but he sometimes finds himself rooting for controversy despite himself. During the 2017 Tour, when a top sprinter, Peter Sagan, elbowed another well-known rider, Mark Cavendish, who fell and broke his shoulder, listenership to the podcast spiked. “That’s what’s f---ed up,” Armstrong tells me. “You wake up and think, We need a crash or something.”

On The Forward, he seems especially drawn to exploring shame, both his own and his guests’. In an interview with Mia Khalifa, a former adult-film star turned social media influencer, Armstrong likened the stigma of sex work to his own struggles. “I have a ton of empathy for you,” he said, after Khalifa talked about her efforts to put the past behind her. “When I open articles about you, every one of them starts ‘porn star.’ ” He went on, saying he, like Khalifa, was trying to reinvent himself. “If you put my name in Google, and pull up 10 articles, every one of those articles starts ‘disgraced.’ ”

If Armstrong believes he’s rebuilt some part of the sports business clout he lost from Nike with Wedu, losing his status as a great cancer warrior still seems to genuinely sadden him. He’ll sometimes record video messages for patients who follow him on social media, but he’s less certain about his prospects as a philanthropist. “Livestrong is never going to reach out again,” he says. “And it almost feels like since they’re out, nobody else will either.”

He says that’s OK. “I’m happy doing what I do, and I’m happy with what I did,” he continues. “The bank is full in my heart.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Daniel Ferrara

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.