Workers Press for Power in Rare Advance for U.S. Labor Movement

Workers Press for Power in Rare Advance for U.S. Labor Movement

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- As protest symbols go, the marchers could have done worse than sarcastic desserts. On the occasion of the Georgia labor commissioner’s birthday this summer, a few dozen unemployment activists arrived outside his office building in downtown Atlanta carrying, among other things, a fudge pie meant to resemble the one from The Help that was memorably made of poop. The chocolate held together reasonably well in the July heat, its symbolism straightforward. “We worked hard, we did what they told us to do,” said unemployed flooring salesperson Lauren Crace, who was protesting in a floral blouse and ripped jorts. “And then we got shit on.”

Crace moved to Florida in 2019 to be closer to elderly in-laws, but because she made most of her income that year back in Georgia, that’s where she had to go to seek unemployment benefits after her son’s day care closed and her company laid her off. To figure that out, she spent a month on the phone with Florida’s Department of Economic Opportunity, including one day when she waited on hold for 10 hours. Then she spent another month wrangling with both states before she received support. Others fared worse, as she saw in a Facebook group she created that quickly swelled with Georgians in search of help. More than 9 million Americans lost their jobs to the coronavirus and got no help from Washington, according to a recent Bloomberg Businessweek review of federal and state data. “Everybody kind of got forgot about,” Crace says now.

American workers—the ones involuntarily benched during the pandemic and the ones who labored through it at great risk so others could stay fed or entertained or alive—are now doing their best to be impossible to ignore. Private-sector union members are authorizing strikes at a rate rarely seen in modern America, with more than 100,000 workers recently threatening or mounting work stoppages in health care, higher education, telecommunications, transportation, television, mining, manufacturing, music, metals, oil, carpentry, whiskey, and cereal. The internet dubbed October #Striketober.

Nonunion workers are voting with their feet as well, fueling a labor market reckoning that’s become known as the Great Resignation. On Oct. 12 the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that an unprecedented 2.9% of the entire workforce, some 4.3 million people, quit their jobs in the month of August, even as the government was confirming it would nuke extra jobless benefits in hopes of forcing people to work.

And all of this is happening as the federal government wrangles over President Joe Biden’s infrastructure bill. The legislation could transform the supply of child-care jobs and the penalties for union busting and, if Crace and her comrades get their way, make the biggest permanent changes to the country’s troubled unemployment system in decades.

It’s a moment with the flavor of 1945, the beginning of a period of massive strikes by what we now call “essential workers.” They unleashed grievances they’d bottled up while getting the country through World War II. Partly through a series of strikes that included 1 in 10 American workers, they ushered in a rare period where employees’ median pay rose hand in hand with their productivity. To recapture that sort of leverage, U.S. labor will need a movement that mobilizes enough people to force reforms.

Unemployment benefits are controversial because, even as stingy and unreliable as they are in the U.S., they give workers a little more leverage against bosses by making them a little less desperate to accept a mediocre offer. They also help people feed themselves while out of a job and help the economy avoid a downward spiral where no one’s getting hired because no money’s getting spent because everyone’s out of work.

Last year the immediacy and magnitude of the pandemic were compelling enough for both parties in Congress to get on board with emergency supplemental benefits of first $600 a week, then $300. That sense of urgency didn’t extend, however, to actually getting the money to millions of qualifying Americans who needed it, and this year, as spring turned to summer, 26 states announced they would end the extra benefits earlier than the federal government’s Labor Day cutoff. Protests among the unemployed have emerged throughout the country, too, in such places as the Las Vegas Strip, downtown New Orleans, and the U.S. Capitol.

At the time of the Atlanta demonstration, Georgia had already cut off supplemental benefits and nixed social distancing rules, but the local Labor Department office remained fenced off and closed to the public, as it has been since the beginning of the pandemic. Crace and the other protesters marched with signs saying “Let us in,” answered only by banners urging job seekers to check out the postings on the agency’s website. “This system has failed us,” said Crace.

Over the summer, activists failed to persuade lawmakers that extending the emergency benefits would help the recovery more than employers claimed this sort of alternative minimum wage would hurt it. (The data tend to support the activists.) But a funny thing happened over the past couple of months: The protests continued. They’ve been buoyed by Unemployed Action, an advocacy campaign that’s working, with little modern precedent in the U.S., to mobilize the lobbying power of the jobless. Crace’s 17,000-member Facebook group for Georgians who struggled to get unemployment insurance during the pandemic is one of many grassroots efforts that have linked up with Unemployed Action. The national campaign is backed by the Center for Popular Democracy, a progressive advocacy group with funding from unions and the foundations of Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz and billionaire George Soros.

Like #Striketober and the Great Resignation, their work is attracting notice in Congress, says Judy Conti, the director of government affairs at the National Employment Law Project, which advocates for workers. “Some members of Congress are absolutely paying attention, and they understand that there’s a different level of worker engagement than ever before,” she says. Proposals for less temporary fixes to the unemployment system were introduced this fall by powerful advocates in both houses, including Democrats Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, representative of New York, and Ron Wyden, the senator from Oregon.

Workers haven’t won much yet, and the millions in crisis can’t just protest forever, but the pandemic has served as a magnifying glass for all sorts of American deficiencies and pathologies. Now, whether on Kellogg’s picket lines or at sailboat protests near West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin’s yacht, workers are wrestling with Covid’s long-term legacy for U.S. labor. If the emerging jobless lobby can win a stronger benefits system, Unemployed Action will have played a significant part.

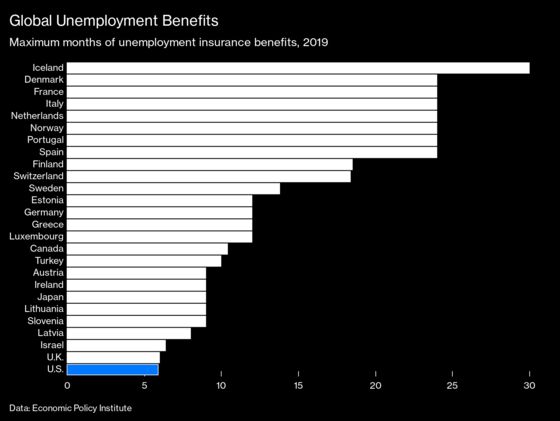

Without Covid supplements, U.S. unemployment insurance is meager compared with benefits in peer countries, delivering beneficiaries roughly 40% of their prior income on average—too little to stave off a crisis for those most in need. It also excludes millions of people, including many temps, part-timers, gig workers classified as contractors, undocumented immigrants, and people who quit their jobs because of domestic violence or child-care needs. Also the present system doesn’t require employers to tell workers such a benefit exists.

Part of the problem is that unemployment insurance is a patchwork. Each state funds and regulates its own UI system, meaning state officials have incentives to reduce aid to their unemployed constituents as a means of lowering the tax burden on employers who lay off workers. Some states max out at less than $300 a week for as few as 12 weeks and make it difficult to claim benefits. (In one extreme example, in Atlanta, laid-off mortgage processor Camille Taylor had to make 160 phone calls to reach a human being and waited five months for her paperwork to be approved.)

This tends to decrease labor costs by limiting workers’ ability to hold out for better offers. One big missing piece of leverage among the jobless has usually been collective action, says political scientist Frances Fox Piven, who co-authored the book Poor People’s Movements. “Unemployed people have been severed from their relationship with each other,” she says. “They’ve also been severed from their relationship with their primary antagonist, their employer.”

Organizing jobless Americans is hard. People don’t identify as unemployed the way they do as teachers or coal miners. Some blame themselves for being out of work, or worry that others will, or fear that becoming a poster child for unemployment will hurt their career prospects. For others, the isolation of unemployment, especially during the pandemic, has hardened pessimism into hopelessness. Yet the desperation of the pandemic helped catalyze the emergence of Unemployed Action.

In the early days of the lockdowns, Rachel Deutsch, then the director of worker justice campaigns at the Center for Popular Democracy (CPD), called a bunch of her employer’s 54 affiliated advocacy groups around the country. She wanted to develop strategies to lobby for paid sick leave and other longtime worker priorities. But affiliates reported back that they were overwhelmed with pleas for help from members who’d just been laid off, so Deutsch and her colleagues at CPD and its sibling political group switched gears. They created Unemployed Action in June 2020, using Facebook, phone banking, word-of-mouth, and ground-level recruits such as Crace to ask jobless workers to attend protests or share their stories. They also created a fund to assist members in need.

“What you heard a lot was people from all different experiences going through this unifying experience of needing the government to be there for them and often finding that it was not,” says Deutsch, who now consults for CPD while caring for her own mom and kids. “There was this opportunity to build solidarity and a shared vision for what our economy should be like and how we should care for one another.” Affiliate groups soon began to organize protests, such as a sleepout on the sidewalk outside the Georgia Labor Department headquarters. Things got tense when state employees confiscated the protesters’ rented port-a-potties, but they released the toilets after police arrived. (The agency says the protesters didn’t have the necessary permit.)

Chenon Hussey, who’d set up her own bustling Facebook group in Wisconsin, says she fielded several emails from Deutsch before deciding to team up. Hussey had been on a family vacation in Aruba when the lockdowns swept across the U.S., emptying Chicago’s O’Hare airport for their return trip. The $100,000 a year she made from public speaking and consulting as a mental health expert vanished almost instantly, but as a freelancer, she was excluded from normal unemployment insurance. The out-of-pocket costs for in-home care for her teenage daughter with special needs quickly became unaffordable. She and her husband made the agonizing choice to send her to a group home, where she remained for a few months until the family could get help from a temporary jobless-assistance program Congress created for contractors.

“It was a pretty big blow—it disrupted her life, and it’s hard as a parent, those decisions—to realize you can’t provide for your kid,” says Hussey, who’s organized sleepouts at the homes of Tony Evers, Wisconsin’s Democratic governor, and Robin Vos, its Republican Assembly speaker. “We had this emergency system set up to jump in, almost like a generator for the country, and that generator wasn’t clicking,” Hussey says. “All these people that thought there was a light that was going to come on, they weren’t getting it. All they had was a broken bulb.”

Today, Unemployed Action’s sprawling network is still working to lobby lawmakers around the country and push its way into the mainstream. Besides in-person protests, the broader organization swarms lawmakers on social media, trains members in skills such as “bird-dogging”—trying to create popular videos by putting politicians on the spot—consults on think tanks’ policy proposals, and coordinates events through its 16,000-member national Facebook group, moderated by volunteers. By design, Unemployed Action brings together some people for whom economic instability is old news and others who were living comfortably pre-Covid. This can lead to friction, but the group’s day-to-day challenges are more basic. One laid-off worker who planned to join July’s protest in Atlanta decided to stay home rather than use up gas driving her SUV 80 miles round-trip. Another volunteer abruptly moved to Missouri. She’d found a job there after months of searching.

The Biden infrastructure package is Unemployed Action’s biggest test so far. Wyden and Ocasio-Cortez have put forward measures for the final bill that would require states to offer 26 weeks of unemployment benefits, add eligibility for workers looking for part-time jobs, and demand that employers tell departing workers how to apply for the benefits. Lawmakers plan to use the reconciliation process to ease passage of the massive infrastructure bill. But that will still require the votes of every Senate Democrat, including Manchin and others who’ve been pushing to shrink the bill’s price tag.

Last month, Hussey logged in to a virtual town hall Unemployed Action held with Wyden, who chairs the Senate Finance Committee. She asked him to spell out his strategy for ensuring that unemployment reform does end up in the final bill. “I’m going to come in as chairman of the committee, and I’m going to fight like hell,” Wyden said. But even winning the incremental changes he’s pushing, he added, is going to be a challenge. “As you’ve seen, not many people back here are talking about this anymore.”

The Biden administration has been sending mixed and sometimes muddled messages. In an open letter to Congress two months ago, Labor Secretary Marty Walsh and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen called “long-term UI reform” a “critical issue” that Congress should take up via reconciliation, while also saying it was “appropriate” for the crisis-inspired benefit boost, which “was always intended to be temporary,” to expire on Labor Day as scheduled. In lieu of that support, they suggested, states could use unspent funds from this year’s American Rescue Plan to help jobless workers wherever the delta variant was posing “short-term challenges” to the labor market.

In an interview with Businessweek a couple of hours after the publication of the open letter, Walsh put it a little differently. “If Florida has to shut down—let’s say the [Covid] numbers continue to climb in the next week or two, and it gets to the point where people are just afraid to go outside their front door,” he said, “then there’s going to have to be a safety net there for the families that can’t go to work because their industry shut down.” So far, zero states have announced plans to take the White House up on its suggestion they deploy Rescue Plan funds for that purpose.

Some of the jobless lobby’s staunchest advocacy partners have entered the government this year, including Michele Evermore, now a senior adviser on unemployment insurance at the Labor Department. That hasn’t stopped the administration from disappointing advocates, as when the White House chose not to resist red states’ cutting off extended benefits early. In late August, Evermore joined Unemployed Action’s weekly Zoom call to talk up the Labor Department’s efforts to help state systems improve. At the end of a question-and-answer session, Deutsch told her the group would like “a little bit more public leadership” from Walsh on the need to extend benefits and overhaul UI. “We would just really urge him to use his bully pulpit,” Deutsch said. “Thanks,” Evermore replied.

Asked about her former comrades’ frustration with her current colleagues, Evermore says the department lacks authority to do some things advocates want, including stopping states from cutting off benefits early. “UI reform is urgently needed yesterday, but it didn’t happen yesterday, so maybe it can happen tomorrow,” she says. “If unemployment goes back down and people stop paying attention to unemployment insurance, then we lose our window to do anything.”

To get some of Wyden’s platform into the final legislation, Unemployed Action plans to keep up the pressure, with members calling their lawmakers and recording personal video messages to spread on Twitter and maybe project onto the walls of senators’ offices. “Stop dancing, do something,” jobless New York retail worker Nicole Marie Polec says in a video message to Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer.

“The challenge that we have been facing has been trying to jump at a political moment of opportunity that is urgent and also very, very crowded,” Deutsch says. “The thing with UI is that the urge to look away is so strong, and so how do you create more situations where you can’t look away?” Whatever Unemployed Action achieves this time, she says, there’ll be more work left to do. The group is counting on the bonds created over months of Zoom huddles to keep people engaged even after they find work.

Even without factoring in Covid, the U.S. is only ever a decade or so away from the next recession, when the unemployment insurance system will let people down again if it isn’t reformed first. As with so many other problems magnified by the pandemic, the first step is just that.

In between the rallying, interstate driving, and caretaking for her mother-in-law, who has cancer, Crace in Florida applied unsuccessfully to more than 150 positions—in health care, call centers, and property management, among other fields—before finally landing another flooring job, managing a store a half-hour’s drive from home. Although she’s relieved to have a steady income again, she plans to remain part of Unemployed Action’s fight. “I’m a whole new person, I think,” she says. “The pandemic opened my eyes.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.