L.A.’s First Step in Housing the Homeless Is Counting Them

L.A.’s First Step in Housing the Homeless Is Counting Them

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In the dark, it takes a sharp eye to spot the silhouette of a homeless encampment behind a row of houses in South Central Los Angeles. But Kenon Joseph knows from experience what to look for.

“Stop!” he tells the driver, who’s only moving her car forward at a crawl, anyway. “I see shadows down there.” He jumps out with a flashlight, and is back a minute later to add five more makeshift shacks and tents to his tally sheet. “You don’t want to miss even one,” he says.

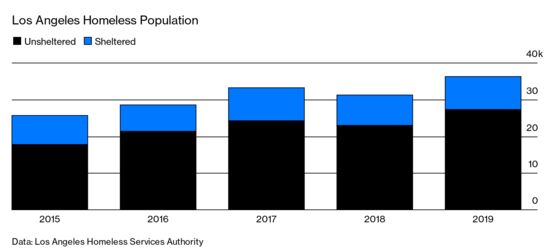

Joseph was one of about 8,000 volunteers participating in an annual count of people living on the streets of America’s second-largest city, a three-day exercise that took place in late January. The final tally won’t be available until later in the year, but in recent times it’s been moving in a troubling direction. It jumped 16% last year, to 36,165. In District 9, where Joseph and his driver—an elderly local woman—are counting, it was up by more than a third.

For LA residents and visitors, it’s a daily reminder of how many people got left out of America’s decade-long economic expansion—and how authorities are struggling to meet their needs. There’s an acute shortage of affordable housing in one of the country’s priciest real estate markets, and similar dynamics are at work up and down the West Coast. California experienced the sharpest rise of homelessness of any state last year, and is now home to more than half of the individuals living on U.S. streets—the so-called unsheltered.

In District 9, according to local Councilman Curren Price, it’s gotten so bad that tents block many sidewalks and shop doors, while pedestrians have to navigate around the shopping carts in which the homeless keep their belongings. Poor sanitation is becoming a public health threat. “Homelessness is definitely the top issue for me,” Price says. “We’re putting more resources than ever into outreach, and the public will is shifting. But still, the numbers are increasing.”

One problem is that wages haven’t kept pace with rents. A Los Angeles renter earning the local minimum wage of $13.25 an hour needs to work 79 hours a week to afford a one-bedroom apartment, according to the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp.

Construction of affordable housing takes time. Homeowners often oppose the addition of low-cost housing to their neighborhoods. And there are lag times for approvals and construction. Los Angeles County voters in 2016 approved a $1.2 billion bond to help pay for 10,000 new units, but the first block of apartments opened only a few weeks ago. The state government has also legislated caps on rent increases and offered tax breaks for developers to build cheaper homes.

In 2017, LA county voters approved Measure H which created a quarter-cent sales tax to pay for homeless services and short-term housing. The measure is projected to raise $355 million annually over its 10-year lifespan. California Governor Gavin Newsom last month asked lawmakers for $1.4 billion to build shelters for the homeless, help with rent payments, and provide medical treatment.

Price, whose District 9 is slated to get more than 1,200 new units, says welfare programs for mental health and addiction also need to be expanded to help people avoid a spiral of decline that can put them on the streets. County officials are trying a preventive approach. This year, they’ll start using digital tools developed by researchers at UCLA and the University of Chicago that mine data from social services agencies to figure out who’s at the highest risk of becoming homeless in the event of even a small financial shock, such as a missed paycheck.

It’s “a proactive way of getting prevention assistance to the highest-risk,” says Phil Ansell, director of the Los Angeles County Homeless Initiative. Still, it isn’t a fix for rising homelessness, which will require “a larger public policy change,” he says. “We’re unable to turn off the spigot.”

California’s homeless problem is attracting national attention, too. President Donald Trump has mocked Democratic leaders in the state for failing to deal with it. Trump’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, Ben Carson, last year denied Newsom’s request for more federal money, blaming the state for over-regulating the housing market.

For Democratic presidential contenders, California is the biggest prize in the upcoming primaries. Recent polls suggest that Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren are best-placed to win there. They’re also the candidates with the most ambitious national proposals to address urban housing shortages and homelessness, promising to spend hundreds of billions over a decade.

Such grand plans seem faraway in Los Angeles, whose residents have taken to neighborhood chat sites to discuss the issue with a mix of compassion and irritation. Meanwhile, officials have to settle for modest solutions that will make the lives of the homeless just a bit less uncomfortable. Price, the councilman, is working with churches to arrange free overnight parking for people living out of their cars and to set up “pit stops” with portable showers, toilets, and washing machines, along with trailers as temporary housing.

The final results of the count will be used to help divide up federal aid. One of the volunteers taking part is Mary Lee, 67, who’s lived in South Central L.A. most of her life; she’s seen some rough times, including the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s. She left the city in the early ’90s and, when she returned in 2007, was shocked to discover how far homelessness had spread outside the city center. Then she fell victim to it herself, ending up in a shelter for a few months with her high school-age son.

Now back on her feet, Lee says she’s angry and frustrated that it’s taken so long for concerted action to address the problem. “It’s a disease that seemed to go from one place and ooze all over the city,” she says.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Ben Holland at bholland1@bloomberg.net, Cristina Lindblad

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.