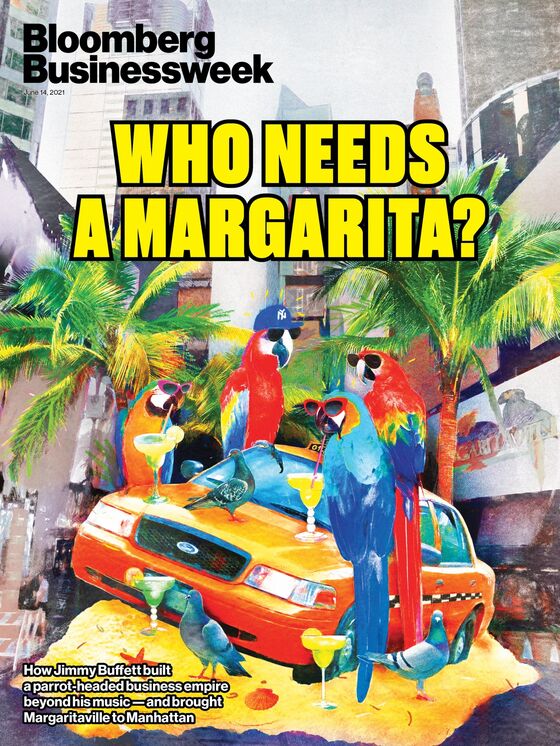

Jimmy Buffett Has Just What New York Needs Right Now: A $370 Million Monument to Frozen Drinks

Jimmy Buffett Has Just What New York Needs Right Now: A $370 Million Monument to Frozen Drinks

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Down the street from the Red Lobster and the shuttered Broadway theaters, a large model of Jimmy Buffett’s seaplane, Hemisphere Dancer, was being uncrated inside his brand-new 32-story hotel. It was 14 weeks before the grand opening of the Margaritaville Resort Times Square, and there was much to do: Lumber and scaffolding were everywhere, and walls of hand-painted palm trees were being touched up. Many of the 234 guest bathrooms were still waiting for their whale-tail faucets. “Ahoy!” shouted a masked worker rolling a giant compass toward the lobby where, hiding under a tarp, was a 32-foot replica of the Statue of Liberty, hoisting a margarita to the blue skies ahead.

The development, which cost almost $370 million and will have taken more than three years to complete when it opens in July, is a treasure map of Buffett brands. Up the lobby escalators, tourists and curious locals will find the 5 O’Clock Somewhere bar and the License to Chill cocktail lounge. A Margaritaville restaurant, garnished in tikis and surfboards, will serve Cheeseburgers in Paradise, and, by the heated outdoor pool, bartenders at the LandShark grill will be pouring LandShark Lagers, the beer Buffett brews with Anheuser‑Busch InBev SA.

Even those who aren’t fanatics of Buffett’s music probably have some vague sense of the Margaritaville lifestyle, which refers to both the hit song—No. 1 on Billboard’s Easy Listening chart in 1977—and its steelpan-inflected vibe, synonymous with slightly baked Floridians searching for that lost shaker of salt. That this mindset also happens to be the antithesis of the pandemic lifestyle is why Buffett is so excited about the project, even after a year of quarantine-related delays. “On the island of Manhattan, as we’re coming out of the pandemic, this is a lucky charm that says it’s time to go back out and have fun again,” Buffett says. “When you can’t go out and soothe the savage beast, you got problems.”

In the 24 years since Buffett founded Margaritaville Enterprises LLC, the company that manages his brand and intellectual property, he’s offered Parrotheads, as his disciples are known, as well as the Parrot-curious, an ever-increasing menu of savage-beast-soothing options. There are luxury resorts, retirement villages, $500 daiquiri makers, Growing Older But Not Up pickleball paddles, lime-wedge-shaped pool floats, salad dressings, casinos, water parks, RV camps, and, where legal, a line of cannabis goods developed with an heir of the Wrigley’s gum fortune. (The Surfin’ in a Hurricane vape pen goes for $35 and can “bring sunshine to your stormy day with significant euphoric effects.”)

It may sound counterintuitive for a 74-year-old crooner whose songs include Too Drunk to Karaoke and Math Suks, but the branding bacchanalia puts Buffett at the cutting edge of so-called experiential marketing. The buzzy trend is all about trying to get consumers not merely to shop or admire a brand, but to swig a double shot of it. It’s why Mark Wahlberg is pushing into burger joints and fitness franchises, why Krispy Kreme’s new “immersive” retail experience features a doughnut-glaze waterfall, and why you can now literally order breakfast at Tiffany’s.

And why not—especially in 2021? After the interminable tedium of stay-at-home orders, in-person attractions, even ones that seem extremely kitschy, have an undeniable appeal. Margaritaville is moving ahead with new developments everywhere from San Diego and Palm Springs to Nassau and Belize, even as a string of other properties have suffered or closed down during the pandemic. The Times Square location, though, is by far the most ambitious.

Buffett has always viewed Manhattan as the toughest nut to crack, or perhaps—per his 1973 classic, Peanut Butter Conspiracy—the toughest Jif jar to swipe. He found this true, first as a musician struggling to win gigs early in his career and now as a marketing tycoon betting his beachy cachet will captivate in one of the world’s largest cities. The risk reminds him of what an actor friend once told him: “If you don’t take New York, Buffett, you ain’t shit.”

The headquarters of Margaritaville Enterprises sits in an office park in Orlando, just across the street from the twisting waterslides of the Universal Studios theme park. Inside, a few dozen employees, with titles such as director of atmosphere, sit at cubicles messy with products they’re testing for possible inclusion in the Buffett empire, such as branded hotel ice buckets.

Pictures of the man himself are everywhere, but Buffett leaves day-to-day operations to Chief Executive Officer John Cohlan, who calls Margaritaville a “real ecosystem” that he estimates was facilitating $1.5 billion in annual sales prior to Covid-19. (The company declines to share actual revenue figures.) Although its brand appears on countless products and hotels, the company doesn’t actually sell or own much besides its intellectual property. The New York real estate firm Soho Properties, for example, oversaw financing and construction of the Times Square resort. The business model, as Cohlan explains it, involves searching out hospitality ventures and consumer goods to Buffettize, enforcing strict design and quality standards, training staff, and earning fees licensing the brand. Buffett takes a single-digit percentage in royalties on portions of partner revenue, which means every Margaritaville hotel suite booked and every “Fins Up Mon’” T-shirt sold. “Same business model as Marriott and Hilton,” Cohlan says.

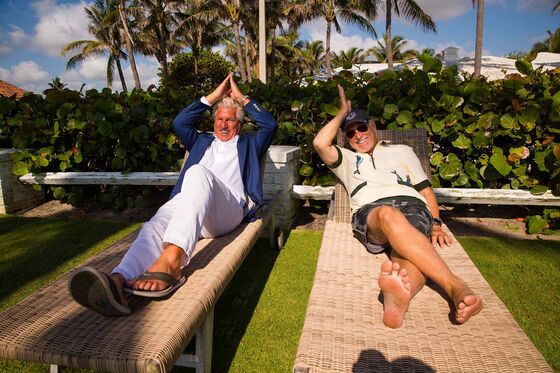

The company got started in the late 1990s, after Cohlan, who was senior vice president of finance at the investment firm that owned Arby’s and Long John Silver’s restaurants, moved to Palm Beach for work. Buffett was spending a lot of time in South Florida, surfing and deep-sea fishing, when not on tour. Cohlan met Jane Buffett through mutual friends, who introduced him to her husband, Jimmy. They hit it off. Later, at one of Buffett’s sold-out shows, an idea bonked Cohlan over the head like a tequila bottle. “I said to myself, ‘Wow, this could really be a brand. Forget Arby’s.’ ”

In fact, Buffett was already intensely aware of the branding power of Margaritaville, having previously fought the Mexican-food chain Chi-Chi’s for the rights to the name. He had dabbled in T-shirt shops and a few eateries, and an up-and-coming beer called Corona even sponsored his concerts. But Cohlan had larger plans, and the pair entered a formal partnership in 1997.

The next year, Buffett released his autobiography, A Pirate Looks at Fifty, a salty travelogue of his Caribbean fishing jaunts and seaplane expeditions. The book references the time he and U2’s Bono flew to Negril, Jamaica, for jerk chicken and, after safely landing, were shot at by local police, who thought Buffett’s taxiing twin-propeller Hemisphere Dancer was smuggling drugs. (Nobody was hurt. The incident inspired his song Jamaica Mistaica.) Ironically, much of the book depicts Buffett avoiding corporate tourist traps and bemoaning how, as he puts it, “Taco Bells and Burger Kings permeate the lower latitudes.” Yet he also wrote of the big money in packaging these experiences in an authentic way.

Cohlan’s first significant opening, a Margaritaville restaurant at the Universal CityWalk retail plaza in Orlando, came in 1999. Executives say Universal had originally wanted a basketball-themed restaurant with Shaquille O’Neal, but after the big man left the Orlando Magic, Margaritaville took over all 20,000 square feet and helped Universal erect a tropical, nachos-heavy shrine to Buffett, with music videos playing on a loop, an apparel shop, and a volcano that reaches to the ceiling, erupting periodically with margarita mix. After eruptions, it makes a booming burp sound effect. Cohlan says the spot did $18 million in sales during its inaugural year, a bounty that’s only risen. The original Hemisphere Dancer, its bullet holes mended, is docked outside, as if Buffett might swing by and take some lucky customers “treetop flyin’ movin’ west along the coast.”

The aughts brought more outposts in Las Vegas and Myrtle Beach, S.C., a SiriusXM radio station, a line of frozen shrimp, and LandShark, which supplanted his Corona sponsorship. Chris Blackwell, the Island Records founder and hotelier who was with Buffett and Bono when the mistaica was made in Jamaica, struggles to explain how Buffett so successfully sold out without ruining his image. Bono probably couldn’t get away with hawking $5.32 Calypso Coconut Shrimp with Mango Chutney Dippin’ Sauce at Walmart. “No, but Jimmy is a fisherman,” Blackwell says. “He just loves the sea. He has such width in so many different areas.”

Perhaps its these far-ranging tastes that have allowed Margaritaville to veer upmarket for its Frozen Concoction Maker, which is basically the iPhone of adult beverage mixers. Alejandro Pena, who led the new venture group at Jarden Consumer Solutions, which licensed and built the product line, says “loud red, yellow, and green colors” spoiled initial prototypes, before his team shifted to a premium design. With stainless steel trim, the “Bali” version features a shaved-ice reservoir and, according to Pena, an “extensively tested” algorithm to mix the ideal margarita, daiquiri, or piña colada. Buffett remembers telling the team that the blenders “had to be as durable as an outboard motor, particularly the Mercury KG-7Q Super 10 Hurricane that I used to race hydroplanes.”

The base model starts at $180. “We came to market at a price point 10x the average blender price, and there were a lot of naysayers,” Pena says. “Sales were off the charts.”

Buffett’s transition into upscale hospitality took off with his move into resorts, where consumers could live the Margaritaville lifestyle in a manner beyond tchotchkes and frozen food. A Florida developer licensed the brand to introduce a $50 million oceanfront hotel at Pensacola in 2010, which promised “barefoot elegance.” Five years later, another developer opened Margaritaville’s current flagship, a 369-room resort in Hollywood Beach, not far from Fort Lauderdale, which real estate investment firm KSL Capital Partners LLC bought for $190 million in 2018.

The $400-plus-a-night property, which is pretty much the opposite of a burping volcano in Orlando, features an 11,000-square-foot spa, a surfing simulator, and eight bars and restaurants, including JWB Prime Steak & Seafood, where Buffett has dined with the pop star Pitbull. It’s not all posh—the gift shop sells $39 “Trespassers Will Be Offered a Shot” signs—but it’s remarkably well designed. Sacred Jimmy lyrics (“it’s a fine line between Saturday night and Sunday morning”) adorn hallway walls, and the lobby boasts a Jeff Koons-style sculpture of a flip-flop. “I could argue that’s our Mickey Mouse,” Cohlan says of the giant blue sandal.

Other companies have attempted to sell a laid-back lifestyle, but Cohlan is dismissive, noting that Andaz, Hyatt Hotels Corp.’s luxury brand, was invented in a boardroom, whereas Buffett’s joie de vivre was cultivated over decades of actual, or at least lyricized, rum-soaked island adventures. (A Hyatt spokesman responds that “the brand was developed in response to extensive global consumer research,” noting that Andaz means “personal style” in Hindi.) Cohlan says Airbnb Inc.’s experiential potential is constrained because it only “stands for the idea that you’re living in somebody else’s place.” Ditto for retailers manufacturing inauthentic attractions to boost foot traffic. “People know Sperry, but if they sold Sperry coffee, you’d say, ‘No! Sperry is a sneaker,’” Cohlan says, sipping a cup of coffee from the nearby Margaritaville roastery.

The scope of Margaritaville’s ecosystem is evident everywhere in Florida. Dispensaries around the state sell Buffett’s Coral Reefer THC. There are Margaritaville vacation cottages and an associated water park in Kissimmee. At the $1 billion Latitude Margaritaville retirement village in Daytona Beach, Terry Bradshaw-lookalikes zoom around in souped-up golf carts, including one shaped like a cheeseburger. This inhabit-the-brand relentlessness isn’t limited to Buffett of course. Not far from Margaritaville HQ in Orlando is Ford’s Garage, a burgeoning restaurant chain featuring the automaker’s branding, where onion rings are served on oil funnels and grease rags are given out instead of napkins.

Not all concepts, though, are winners. As Cohlan recalls: “A very serious guy, who owns a lot of dental offices, called me up and said, ‘Why should it be so painful to go to the dentist? How about Margaritaville Dental? There could be palm trees in the waiting room.’” That was an obvious no, Cohlan says. Margaritaville electric toothbrushes, on the other hand, were a yes. “Take a vacation from your old manual toothbrush,” as HSN put it, offering a set of three for $39.95.

Considering how many ventures the company has slapped Jimmy’s name on, what’s the process for deciding which ones to greenlight? Chief Investment Officer Evan Laskin describes the brand’s corporate compass as an Amazon.com-esque “flywheel”—Jeff Bezos’ idea that investing in different divisions will eventually create organizational momentum—and shows off a printed copy. The chart wouldn’t exactly impress Bezos. It’s a list of Margaritaville’s various business categories—consumer products, dining, lodging, media—arranged in a circle. Squint hard, though, and the Margaritaville flywheel does conjure up a life cycle of brand consumption, especially as it targets younger audiences that are less familiar with Buffett’s lyrics. LandShark beer, which consumers may not realize is related to the singer, might hook twentysomethings to LandShark restaurants, which in turn might eventually reel them to the brand’s backyard products (coolers, lawn chairs, a $900 constructible Surf Shack Bar kit), hotels, and, as they get older, perhaps even Margaritaville’s vacation and retirement homes. Laskin says he was even once pitched on building Margaritaville Graveyards. “I’m not doing cemeteries,” he says. “We stop at some point.”

This flywheel has become a key selling point for business ventures. Esther Newberg, co-head of publishing at talent agency ICM Partners, recalls Cohlan pitching her on a Margaritaville recipe guide that would feature Buffett’s favorite margarita along with other Jimmy-approved meals and cocktails. “I said to John, ‘I really don’t do cookbooks,’ ” she remembers. “And he said, ‘But this cookbook will be in all our hotels. It’ll be everywhere!’ ”

Another key part of the company’s process is ensuring that business partners abide by its aesthetics. Pat McBride, founder of its longtime design firm, Vermont-based McBride Co., says he avoids any generic design that might “look like a prop at Six Flags,” and instead focuses on crafting elements that make the experience feel like the real deal. The leather stools at JWB Prime, for example, feature stitched rum labels from abandoned island distilleries. “If those chairs didn’t have that stitching, I guarantee it wouldn’t feel the same,” McBride says.

Joe Ginel, Margaritaville’s atmosphere director, says that this subtle science includes the settings for resort Wi-Fi passwords (for instance, “spongecake”) to nailing the music playlists at each destination. “For every four songs, there’s always a Jimmy song,” Ginel says, describing the general formula. “In Orlando, for every three songs, you get two back-to-back Jimmys. If you go to Key West, we flip the script: It’s a lot of Jimmy.”

In the spring of 2020, construction in Times Square was halted by state order, and Margaritaville hotels around the globe soon closed temporarily. Darby Campbell, a real estate developer who’d opened an $85 million Buffett hotel just five months earlier in downtown Nashville, saw $1.5 million in bookings evaporate immediately. He laid off almost his entire staff of 118 employees and ceased taking reservations. “We actually went so far as to drain the pool,” he says. “It was brutal.”

Hotels in Grand Cayman and Vicksburg, Miss., shut down for good. But Cohlan says Margaritaville’s revenue dropped only 30% in 2020, buoyed by soaring sales of daiquiri makers and branded bicycles, as well as purchases of $300,000 Latitude retirement homes, which doubled during the pandemic. Meanwhile, the company pushed ahead with 25 developments, including a boutique hotel chain called Compass.

The pandemic wasn’t the first time the company had hit choppy waters. A humdrum Cheeseburger in Paradise restaurant chain changed owners several times before Buffett severed his association in 2012, leading to a slow demise. (A Margaritaville spokesperson says the brand has reclaimed the trademark and will be introducing a food-delivery concept under that name in Chicago.) In 2014, a 68,000-square-foot Margaritaville casino shut down in Biloxi, Miss., partly because it had no attached hotel and was in a bad location, the company says. Margaritaville later opened a waterfront resort in Biloxi that’s operating today. Members of the rock band Kiss are taking over branding for the old gambling venue, which sat empty for years. A number of lawsuits have chased Margaritaville’s developers over the years.

Executives chalk up the stumbles to the unforgiving real estate business. “There’s always lawsuits,” says Laskin, the investment chief. The disputes serve as a constant reminder that Buffett’s team has to be ever-vigilant with whom they jump in a hammock, because it’s Buffett’s reputation that’s harmed if anything goes wrong. “When someone has a bad experience, they don’t say, ‘Those KSL guys gave me a bad experience,’ ” says Cohlan, referring to the owners of the Hollywood Beach resort. “They say, ‘Those Margaritaville guys gave me a bad experience.’ ”

The shuttered Grand Cayman resort apparently turned into one of these bad trips. In July 2020, the Cayman Compass, a local paper, reported that the property owners were being sued for more than $1 million in unpaid debts. Two investors involved, who asked not to be named because of ongoing legal issues, say the construction was shoddy and that promised attractions such as a big waterslide never materialized. Even the iconic flip-flop statue, they add, showed up months after the hotel first opened. (It’s since been removed from the entranceway and now sits, among discarded junk, in a nearby parking lot.) Cohlan says the resort fell below Margaritaville’s hospitality standards and that they were forced to “de-brand” it. The owners couldn’t be reached for comment.

Despite its island associations, the Margaritaville brand performed better in the mountains during the pandemic. Campbell owns two other Margaritaville hotels near the Dollywood resort in Tennessee, a water park in Georgia, and several tree-lined RV camps. He says revenue at his outdoorsy properties in Tennessee shot up significantly in 2020 from the previous year. The Nashville hotel has also since reopened and is fully booked on most weekends.

For now, Campbell says, “it’s really the bachelorettes and the party people coming in Thursday through Sunday.” But, he mentions that weekday traffic seems to be returning, and the Oates half of the pop-duo Hall & Oates recently stopped by for an interview at the lobby’s Margaritaville radio studio. Golfer John Daly dropped in another time too. “We had a little pool party,” he says.

During quarantine, Buffett mostly hid out at his Malibu home. In a Zoom interview in late April, he appears before a virtual background of a sandbar under the username Bob Marlin. “One of my many pseudonyms,” he says, grinning.

He spent the pandemic surfing and making two albums, comparing the self-isolation to the sea voyages he used to charter from Newport to Bermuda and the Virgin Islands. “Inevitably, you’d be hungover, something would break, a storm would come, and suddenly you’d have this thought, What am I doing out here?” Buffett says. “Then you’d just have to take yourself aside and go, ‘Hey. Settle in.’ ”

With the storm finally passing, at least in the U.S., Buffett says he’s preparing to head to New York for a media event ahead of the Times Square grand opening. He’d had bad luck during his last journey there. His 2018 Broadway musical, Escape to Margaritaville, closed quickly after blistering reviews. (“If you’re not drunk or a Parrothead,” wrote the New York Times, “you’re in trouble.”)

But he seems optimistic and has been reading The Island at the Center of the World, a history of the Dutch takeover of Manhattan. He says all his “time on the water” will help “make the island of Manhattan behave like the island of St. Barts.”

In many ways, the Manhattan hotel symbolizes Margaritaville’s post-Parrothead ethos—and its inevitable post-Jimmy future. After all, the pirate is now looking at 75. “It’s legacy time for me,” he says.

Visitors to Buffett’s newer properties will see fewer and fewer photos and videos of the white-goateed performer, and Laskin makes a point of clarifying that Jimmy’s weed venture is completely separate from Margaritaville Enterprises. When a PR minder was out of earshot during one property visit, a resort manager whispered that Cohlan didn’t want him even talking about Buffett during our interview: “He said, ‘Stay off the Jimmy subject!’ ” (Cohlan doesn’t recall saying this and adds, “We love talking about Jimmy.”)

Buffett is, as you’d expect, a lot more chill than the businesspeople who manage his affairs, but he is aware that the brand has taken on a life of its own. He doesn’t really drink margaritas that often anyway these days. “I’m not a big pot smoker, but I like to get a little buzzed every now and then, of course,” he says.

He again compares the situation to life at sea, where you need a good crew to stay the course. “How much further can you go with this? I don’t know. I’m pretty happy with where we are right now. Do I want to start an airline? No.”

Warren Buffett, an old friend (though not a relation) who announced his succession plans for Berkshire Hathaway Inc. in May, thinks that Margaritaville only has upside, so long as Jimmy is involved—or at least is perceived to be. “I don’t think he could sell the name to some guy on Wall Street,” Warren says, chuckling. “It’s not like Howard Johnson’s, or various businesses that were identified with an individual and they institutionalized it. Jimmy is the institution.”

The good thing, Warren quickly adds, is that Jimmy will keep going well into his 80s and 90s, like Warren himself. That means decades of additional consumers experiencing the Margaritaville lifestyle. “Jimmy doesn’t need a revolving group of fans,” Warren says. “He basically just accumulates them, and he doesn’t lose them. Except when they get old and die.” —With Olivia Carville

Read next: The B-52s’ Kate Pierson Is Selling Her ‘Love Shack’ for $2.2 Million

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.