Japan’s Unions Risk Irrelevance as Contract Workforce Expands

Japan’s Unions Risk Irrelevance as Contract Workforce Expands

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In a three-story apartment building in a residential area of Japan’s capital, a tiny sticker on the door of Room 203 announces the presence of the Women’s Union Tokyo. The timeworn but tidy apartment is filled with books and decorated with signs bearing uplifting messages. One reads, “#With You”; another, “No Longer Alone.” Inside, Keiko Tani and Hiroko Nitta counsel women who’ve lost their jobs during the pandemic. Demand for the pair’s services is higher than ever.

Their clients are mostly part-timers and contract workers, who in Japan are the first to be cut in a downturn. “We’ve tried to empower women by representing their voices so that they can keep working with pride,” Tani says. “But in reality, the situation has been deteriorating.”

Even in the best of times, Japan’s nonregular workers, a category in which women are heavily represented, enjoy few job protections compared with salaried employees. The divide has become particularly stark this year: 680,000 nonregular workers have been cut, while the ranks of regular workers have held steady. Tani and Nitta say Japan’s traditional unions, male-dominated and with more resources than theirs, share in the blame. “Labor unions made of regular workers have let nonregular workers be used as a buffer so that they could protect their own jobs in a downturn,” Nitta says.

Jobs-for-life were the norm in Japan until the early 1990s, when the bubble economy collapsed into a prolonged malaise. Unions didn’t need to fight for raises for their members, because they were a given. After the boom, they largely stood on the sidelines as companies moved factory jobs abroad and stepped up hiring of contract and part-time workers to cut costs.

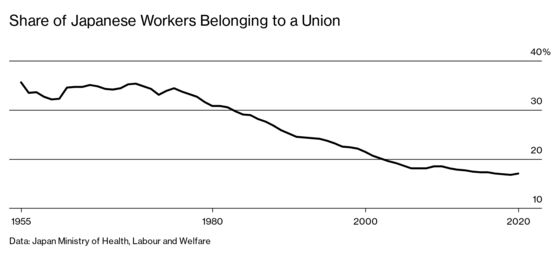

Most of the larger unions have made no real effort to sign up nonregular workers, which is a big reason many have lost their clout. The unionization rate fell to a record low of 16.7% in 2019 and stood at 17.1% in 2020, from close to 25.2% in 1990, according to government data. The rate for women, who represent more than two-thirds of nonregular workers, was 12.8%; for part-timers it was 8.7%.

Michiko Kawai, 62, has lost all of her income since March when she was put on leave from her job handing out product samples at Tokyo-area supermarkets. The company for which she’s worked for the past 11 years on a contract basis hasn’t paid her legally mandated furlough allowance. Frustrated, Kawai turned to Haken Union, which specializes in representing nonregular workers. “I don’t think the company will give me work again,” she says.

Shuichiro Sekine, the general secretary of Haken, which has about 300 members, says businesses routinely obstruct his organization’s efforts. “Companies don’t accept requests when nonregular workers organize a union,” he says. “They push back our requests even if they agree to sit down with us.”

At Hiroshima Electric Railway Co., the in-house union reached an agreement with management in 2001 to sign up nonregular workers. Masaaki Sako, head of the union, recalls hearing the employees say they liked their jobs, but the pay was poor and the one-year contracts left them feeling vulnerable. “I thought, ‘I’ve got to do something for them,’ ” he says.

Almost a decade later, the union was instrumental in getting the company to convert all nonregular workers, who accounted for almost a third of its workforce, to regular positions. As part of the negotiations, the union persuaded older members to take a pay cut to close the gap with newer hires.

The deal raised morale inside the company, Sako says, but other unions gave him the cold shoulder. “I got a sense that the mentality of union higher-ups had rotted,” he says. Today almost all of the railway’s 1,800 employees belong to the union.

During his almost eight years in office, former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe regularly prodded Japanese companies to raise pay, saying their stinginess had contributed to a deflation mentality that held back growth. Under his watch, Japan’s minimum wage went up 20%, to 901 yen ($8.70). At the end of August, Abe announced he would be stepping down because of health problems. That same month, the labor ministry announced a 1‑yen increase for the current fiscal year.

Annual wage negotiations, a springtime ritual, will provide a test of unions’ leverage. Rengo, the country’s largest umbrella organization of labor unions, is seeking a raise of about 2% for its 7 million members, as well as a minimum hourly wage of 1,100 yen regardless of employment status, to narrow inequality among workers. Rengo’s membership ranges from heavyweights such as the unions covering Toyota Motor Corp. employees to smaller entities like Haken Union. Only 18% of its members are nonregular workers. “We are behind and playing catch-up,” says Rikio Kozu, who heads Rengo. “Few Japanese see unions as relevant to their lives.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.