Japan’s Pot Laws Are Harsh, But Its Pensioners Invest in Growers

Japan’s Pot Laws Are Harsh, But Its Pensioners Invest in Growers

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Even as much of the world embraces legal pot, Japan is sticking to its long-standing zero-tolerance policies. The country’s ultra-harsh penalties for possession include prison terms as long as five years for the equivalent of a few joints, and in January the government floated a proposal to outlaw THC in the bloodstream, which could make it illegal to use weed during an overseas vacation. The national pension fund, meanwhile, is investing in the stuff.

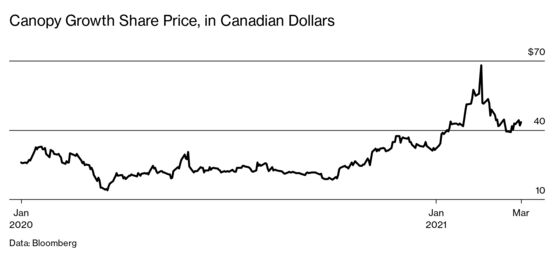

Financial disclosures show Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) accumulated stakes totaling some $80 million in at least three pot companies. With 1.7 million shares of Canopy Growth Corp., which trades on the Ontario stock exchange under the ticker WEED, the fund would be among the top 12 holders of the recreational marijuana dealer. Its shares in Cronos Group Inc., a Toronto company that owns pot brands such as Spinach and Happy Dance, are valued at about $17 million. And the $7 million stake it says it held in Aurora Cannabis Inc., which focuses on medical marijuana, would make it a top 10 shareholder. “It’s a complete contradiction,” says Michiko Kameishi, a criminal defense attorney in Osaka who’s represented dozens of defendants in pot cases. “People’s lives get ruined for this.”

GPIF spokeswoman Nao Honda declined to say whether the fund still owns the stakes, which it reported in disclosures last summer. Even at $80 million, the investments would be only about 0.005% of GPIF’s $1.6 trillion in assets. She says GPIF’s rules bar it from direct purchases of shares and that the vast majority of the fund’s stocks are bought via accounts intended to track equity indexes. “We are dedicated solely to ensuring long-term returns for our members,” she says.

GPIF—the world’s largest public pension fund—is confronting an issue faced by many managers of public money: How to ensure good returns while respecting the moral and legal principles of the community. State-managed funds in the Middle East, for instance, typically avoid investing in companies that specialize in activities such as gambling or selling alcohol or pork, but many hold shares—either directly or through other funds—in businesses that would violate a strict interpretation of Islamic law. The sovereign wealth fund of Norway, where recreational pot use is illegal, invested in Canopy and other pot companies but sold the shares after complaints from the Norwegian Narcotic Officers Association. And more than a dozen pension funds for U.S. states, including one for teachers in Kentucky, where even medical marijuana is illegal, hold stakes in a San Diego real estate fund that leases property to licensed cannabis growers.

It would be almost impossible to entirely avoid putting public money into companies that engage in activities that conflict with a society’s values, says Meeta Kothare, an adjunct professor at the McCombs School of Business in Austin, Texas. Most pension funds hold shares in index funds, which invest in dozens or even hundreds of companies that can be involved in myriad businesses. And regulations often lag shifts in social mores, Kothare says. For her, a more important question is whether GPIF is taking too big a gamble with pensioners’ money by investing in pot, a drug that remains illegal in most places. But she says many such funds have increasingly embraced risk because safer investments such as sovereign bonds no longer offer the returns needed to provide for retirement—especially in Japan, the country that the World Health Organization says has the world’s longest life expectancy. “I do worry about how pension funds are getting riskier and riskier over time,” she says. “That is the ethical issue.” —With Michael Arnold and Matthew Martin

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.