Failure of Trickle-Down Abenomics Is Top Issue for Japan Voters

Failure of Trickle-Down Abenomics Is Top Issue for Japan Voters

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- As Japan heads into a national election on Oct. 31, concerns over inequality are taking center stage. In a country that once defined itself by the slogan “100 million people, all middle class,” the pandemic has shined a spotlight on the gaps between the haves and the have-nots. It’s cemented the belief among many Japanese that the trickle-down economics of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and some of his predecessors has eroded living standards for the majority, while a few rode a wave of gains from soaring asset prices.

Fumio Kishida, who was sworn in as prime minister on Oct. 4 and is expected to lead his Liberal Democratic Party to victory in this month’s balloting, says Japan needs a “new capitalism” that emphasizes distribution of wealth as well as economic growth. But he’s been short on tangible policies for how the two objectives can be bridged.

Opinion polls show that while a large portion of the Japanese public has become disenchanted with neoliberalism, the country is divided on economic priorities. In a survey by Jiji Press published this month, almost 63% of respondents said there should be a rethink of Abenomics, which many believe has prioritized corporate profits over the welfare of workers. Yet in a poll by the Nikkei newspaper, 47% said economic growth should be the top objective, compared with 38% who said distribution was more important.

Kishida has already learned the hard way that it pays to be vague. His comments in early October suggesting that his administration was considering raising the capital-gains tax triggered a stock market selloff, prompting him to walk back the idea. Shigeto Nagai of Oxford Economics wrote in an Oct. 19 note to clients that investor fears that Kishida will make a radical break from Abenomics—with its emphasis on deregulation, corporate tax cuts, and other policies to stimulate private-sector investment—are “overblown.” After all, Kishida won the contest for the LDP leadership with support from Abe’s faction, Nagai wrote.

The Covid-19 crisis has exposed the precariousness of some of the much-trumpeted economic achievements of recent years. Kenji Hashimoto, a professor at Waseda University in Tokyo who’s studied rising inequality in Japan in the postwar period, says data he’s compiled show that despite government policies to limit economic scarring from the pandemic, the 9.1 million Japanese in the bottom income bracket suffered twice as big a hit to earnings as the 2.2 million people in the highest income bracket.

Mitsue Tashiro, Save the Children’s program manager in Japan, says the NGO has been handing out food parcels for the first time in its almost 40 years in the country. Of the more than 3,000 households that received a package this summer, about 40% still had either no income or less than half of their pre-pandemic income. “We’ve heard from parents who weren’t eating so their children could eat,” says Tashiro. “With the schools shut, some also felt they weren’t giving their kids enough food.”

Boosting women’s participation in the labor market was a top objective for Abe, and by 2016 Japan had overtaken the U.S. on that metric. However, most of the gains came in so-called irregular employment, a term that encompasses positions that are part-time, temporary, or under contract. Women make up a larger percentage of part-time workers in the hotel, food service, and retail industries—sectors that absorbed a disproportionate share of the job losses triggered by the Covid recession. About 700,000 Japanese women exited the workforce in April 2020, compared with 390,000 men, according to government data.

Rie Murai, a single mother of two high school-age children and a 1-year-old, says she’s having as tough a time making ends meet as at the start of the pandemic. The Osaka resident had a full-time job caring for the elderly but had to quit, because her employer would not give her a more flexible schedule to accommodate having to look after her youngest. “My income’s about half what it used to be,” says Murai, who now works in retail but for fewer hours at less pay.

She’s skeptical about a proposal floated by Komeito, a junior party in the governing coalition, to distribute a one-time payment of 100,000 yen ($880) for each child aged 18 or younger. Handouts don’t address the root causes of inequality, she says. Murai isn’t putting much stock in Kishida’s pledge to raise pay for caregivers attending seniors, either. “They’re always saying that caregivers’ wages need to rise, yet they’ve stayed so low,” she says.

Even before the crisis, more than half of Japan’s single-parent households—most of them headed by women—lived below the poverty line, compared with about one-third in the U.S. Yukari Tamashiro, the director of NPO Happy mam, an Osaka-based support group focused on single mothers, says her organization has been distributing twice the number of food parcels than it did before the crisis. “Those who are already poor are getting poorer,” says Hiroshi Ito, a director at Tokyo’s social welfare council for single-parent households.

At the other end of the spectrum, Japan’s ultrarich have been splurging on luxury items this year. Shota Ueno, a merchandiser for department store Isetan Mitsukoshi, says high-end watches have sold at twice the pace of 2019, with Rolexes, Patek Philippes, and Richard Milles that fetch more than 10 million yen apiece doing particularly well. “Sales of high-end jewelry move the way the stock market goes,” says Ueno.

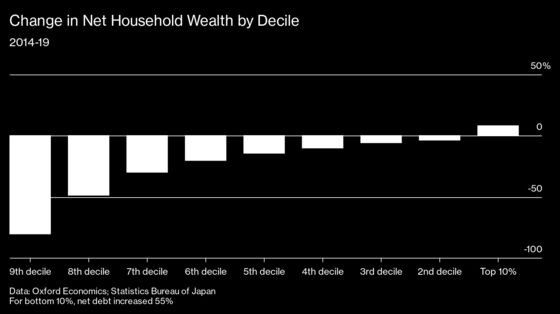

Japan’s benchmark stock index roughly doubled during Abe’s seven-year tenure and is up more than 50% since the start of the pandemic. However, since only around 15% of household assets are held in stocks, bonds, or investment trusts (compared with about half in the U.S.), only a small portion of the population has captured the benefits. Working off government data, Oxford Economics’ Nagai has shown that household wealth for the richest 10% advanced 8.2% from 2014 to 2019, while falling by 3.5% across the board.

Stagnant pay is a big part of the problem. While Abe repeatedly called on companies to increase salaries, average monthly pay rose just 1,106 yen from August 2012 to August 2021.

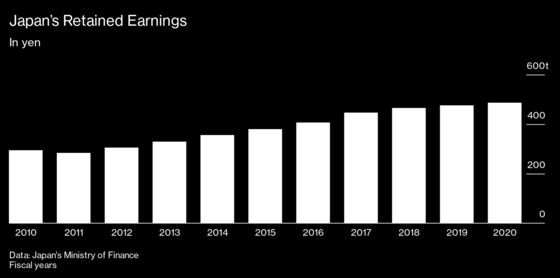

Corporate profits have mushroomed by 30% since fiscal 2012, and Japan Inc.’s stash of retained earnings has swelled to 484 trillion yen at the end of March 2021. Businesses have justified the large cash holdings as security against unforeseen events—yet when the pandemic came along, rather than drawing down their cash stockpiles, they kept adding to them.

Kishida’s message on addressing inequality is the most explicit public admission by a Japanese leader in recent years that the country’s growth strategy has been leaving many behind. Measured by the Gini coefficient—a standard yardstick for income equality—Japan is more egalitarian than the U.S. or the U.K., yet the perception that there’s a growing divergence in wealth has influenced the policy platforms of other parties in the election, too. The LDP and its coalition partners are facing off against an alliance that includes the Japanese Communist Party, which is pledging more drastic policies such as cutting the sales tax and raising the corporate income tax.

So far, Kishida has pledged to sharply increase tax breaks for companies that raise wages and to boost pay for kindergarten teachers and nurses, along with that of caregivers to the elderly, saying economic growth will generate the funds needed to cover the higher compensation. But Kumiko Murakami, vice president of a labor union for caregivers to the elderly, says that “whenever the question of raising pay for care workers has come up, there’s always been the problem of how to fund it, and it never goes well.”

Also, the small and midsize companies that employ most of Japan’s workforce don’t pay enough corporate taxes for Kishida’s proposed breaks to serve as an incentive, Hashimoto says. At best, they could improve the wages of those who work for larger companies, who already tend to be better off. “It’s much better to just put money directly in the pockets of workers,” he says. In his view, a more effective policy to reduce inequality would be to raise the minimum wage to 1,500 yen an hour, from a national average of 930 yen. Says Hashimoto: “As long as the ruling coalition maintains a stable majority, you won’t be able to make progress on equality.” —With Isabel Reynolds and Grace Huang

Read next: The World’s Top Business Cities Are Still Failing Working Women

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.