The Salt King of America

The Salt King of America

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Ben Jacobsen is standing over one of the rectangular oyster pans that fill each day with about 8,000 gallons of seawater from nearby Netarts Bay, a protected estuary along Oregon’s northern coast. He thrusts an index finger toward a tiny, translucent speck beneath the surface of the brackish, near-gelatinous water. The speck joins another, then another, until a dime-size cluster forms. As the crystal drifts to the bottom of the pan, Jacobsen grins. “Beautiful,” he says.

The flakes are different from the salt you might sprinkle on fries at a diner: larger, brighter, crunchier, and, if the discerning taste buds of North American chefs are to be believed, more flavorful. Jacobsen Salt Co.’s “pure flake finishing salt” has made him popular with Michelin-starred restaurants, taco trucks, Williams-Sonoma stores, small grocers, and Antoni Porowski of Queer Eye. “The way it dissolves is different. There’s this brininess as opposed to this mouth-deadening salt flavor,” says Megan Sanchez, co-owner and chef at Güero, a restaurant in Portland, Ore., known for its tortas.

Jacobsen, who’s 43, and others who share his passion have helped to change how Americans think about salt—the marriage of sodium and chlorine, and sometimes potassium and iodine. The global market for gourmet salt totaled $1.1 billion in 2016; it’s expected to grow to $1.5 billion in the next decade. Jacobsen’s roster so far includes his flake salt, a coarse kosher salt for everyday cooking, and a line of flavor-infused salts, such as an outré blend of smoked chili peppers and San Pablo worms harvested from Mexico’s Oaxaca Valley. He’s also created a line of salt-based seasonings for meats and ramen. “Salt is one of those things, in the U.S. at least, that has been pretty easily overlooked,” he says. “So I think we’re fortunate to get some attention. But I also think we make the best salt on the planet.”

Jacobsen found his calling after a detour through Silicon Valley. He attended high school in Portland and got a degree in geography from the University of Washington, then moved to San Francisco in 1999. He spent a couple of years at Tickle Inc., an early social networking site that was acquired by Monster.com in 2004 and subsequently shut down. He then decamped to business school in Copenhagen, nearer to his Scandinavian extended family. In 2006 he moved to Oslo to work for Opera Software, an experience that convinced him he could successfully launch a startup. In July 2009 he set about trying to develop an app for curating other apps. But founding an app-discovery company a year after Apple Inc.’s App Store opened might not have been the wisest of moves. He and his business partner had different visions for how to proceed and couldn’t build it quickly enough. Without software engineers or money to hire them, the company went nowhere. Jacobsen describes the experience as “a slow, painful burn and death.”

But his time in Europe had given him a better idea. A girlfriend had floored him by spending $10 on a small package of Maldon, a British brand of sea salt known for its pyramid-shaped flakes. He remembers sprinkling it on top of a cheap meal of canned mackerel, olive oil, arugula, and tomato sauce. “I was blown away by how much better good salt made something,” he says.

After moving home to Portland, he scoured stores, looking for flaky salts, but all he could find was Maldon. He became obsessed with producing his own sea salt. His first attempt involved plunking an inflatable kiddie pool in his backyard and filling it up with ocean water, to no avail. “So I started trying to heat seawater in pots and pans and ovens,” he says. He found that steadily applying low heat over the course of a day produced satisfyingly tasty grains. Those early experiments formed the basis of the two-week process Jacobsen Salt uses at Netarts Bay.

Set against the backdrop of Douglas fir trees in Tillamook State Forest, Netarts Bay is home to the 6,000-square-foot facility where Jacobsen’s 11 full-time saltmakers produce 180,000 pounds each year. He didn’t arrive there by accident. In June 2011 he loaded his Portuguese water dog, Lykke, and a bunch of five-gallon buckets into his Subaru Forester and made his way north to Neah Bay in Washington, gathering 27 samples of seawater as he went. Once back in Portland, he made salt from each sample in search of the crunchiest flakes, the best coloring, and the right aftertaste. The waters of Netarts Bay proved to have a winning secret ingredient: oysters, thousands of which populate the seven-mile-long estuary.

Jacobsen spent the rest of his summer weekends guarding steam kettles in the shared commercial kitchen of KitchenCru, an incubator for culinary startups in Portland. Every Friday he’d get to the kitchen and spend the next 72 hours there, taking the occasional half-hour nap in the dry pantry as he sought the optimal temperature to form large flakes.

The main traits of a great salt are generally held to be color, texture, and flavor. Color is pure presentation—how white a crisp, shiny salt looks sprinkled on food. A salt’s texture affects where it lands and how it dissolves on your tongue, which influences taste. Flavor, following from the chemical composition, is what really distinguishes one salt from another. Sodium chloride is the backbone, but salts with a bitter aftertaste contain potassium. Something like Maldon has virtually no potassium. “Flaky salts have a really high percentage of sodium chloride and really trace amounts of other minerals,” says Dan Souza, editor of Cook’s Illustrated and a chef on the PBS cooking show America’s Test Kitchen. Salt that’s pleasingly tangy will have had calcium and potassium deposits boiled out, followed by a slow, steady evaporation of magnesium.

Jacobsen eventually brought samples of his salt to a new-vendor fair hosted by a local grocery chain. Ryan White, the chain’s buyer, liked it so much he asked for orders for each of the grocer’s 13 stores. With a viable business in sight, Jacobsen applied for a saltmaking license from the state department of agriculture, received a permit to pump water out of the bay, won U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval, got funding from friends and family, and formed his company. For several years he drove bay water to Portland before finally buying an old oyster farm on the Netarts coast, adding some tanks and pans, and hiring a staff. He was, as far as he can tell, the first person to set up a salt works on the Oregon coast since Lewis and Clark, who temporarily established one about 50 miles north in the early 19th century.

Just outside his facility, Jacobsen hoists a chunk of calcium as big as a human head. “This is what oysters are filtering out of the seawater to build their shells,” he says. After making its way through a lone PVC pipeline, the water reaches a drafty shed where two gargantuan pots, wider than monster truck tires, complete the work the oysters begin. The pots are boiling hot; Jacobsen says he’ll never reveal the precise temperature.

The filtered brine is transferred to the oyster pans, where it slowly cooks over a period of three days. During this “low-boiling” period, as magnesium leaches out, salt crystals form and clump together, densifying and sinking. When a batch is ready, it’s shoveled from the pan, becoming flake salt. The brine is then boiled off completely, leaving smaller, coarse crystals that become the basis of Jacobsen’s kosher salt.

Batches of both varieties are then transferred to drip pans and dropped off in two sauna-like dehydrator rooms, where they dry out for three more days. Kosher salts are packaged on their own or sent out for flavor infusion. The prized product, though, is the flake. Before being packaged, it’s sifted by hand in gold pans and sieves to remove any trace of calcium. “This is gorgeous,” Jacobsen says as he holds up a handful of blindingly white flakes. I take a pinch. “Isn’t it delicious, too?” he asks. It’s briny, but not bitter. Tangy, but not tart. I bite down, and the salt makes a crunch, like a potato chip.

The day after our tour of the bay facility, Jacobsen invites me into the warehouse section of the company’s 27,000-square-foot headquarters in Portland, where the Netarts Bay flake gets packed. Inside a glass-enclosed clean room, three packers shovel white flakes from bins into small plastic bags. Each worker wears a long plastic poncho, a hair and face mask that leaves only enough room for their noses and eyes, and tight black gloves. Scales line their respective workstations. “All of our salt is hand-packed,” Jacobsen says. “It looks a little druggy, a little Walter White-esque, but whatever.”

Jacobsen owes some of his success to good timing. According to Souza of America’s Test Kitchen, chefs and restaurants were already beginning to adopt carefully produced, flaky sea salts as a way of making their dishes stand out. Then cookbooks, cooking shows, and recipes in mainstream publications pushed the trend to the general public. “There’s been a ton more in the last 5 to 10 years from a publishing perspective on salt and how to use it,” Souza says. “I think we’ve always loved salt in this country, but Americans now think about salt in a way they absolutely didn’t before.”

When it came out in 2011, Jacobsen’s salt was $5.50 for a 4-ounce bag. But once it developed a cult following in Portland, with Güero’s Sanchez and Gabriel Rucker of Le Pigeon among its champions, Jacobsen swiftly forged partnerships to spread it across the U.S. Restaurants from Rustic Canyon in Los Angeles to Jean-Georges in New York City now feature Jacobsen salts in their dishes; you can also find them in every Williams-Sonoma store, as well as at Whole Foods Markets, specialty shops, and either of Jacobsen’s two facilities. The 4-ounce bag of flake salt costs a bit more now: $12.50.

Dick Hanneman, who spent 24 years as president of the Salt Institute, a now-defunct global association of salt companies, takes a skeptical view of the trend. “The development of the American production of sea salt is a fantastic marketing achievement,” he says. “Somehow, sea salt, which is the cheapest salt to make, has been sold to the public as a superior salt.”

Jacobsen doesn’t disclose revenue figures, beyond saying they’re small but significant enough that he’s been able to start paying his family back. He’s hoping that his chief financial officer, Mary Ellen Signer, can help him keep expanding the business. In the decade she served as CFO and chief operating officer of Stumptown Coffee Roasters, Signer saw the company grow from $6 million in revenue to $68 million.

The pair have high hopes for their new seasoning line, with varieties for steak, seafood, tacos, and ramen. Three of them actually contain salt from Italy, though the steak seasoning makes use of Jacobsen’s sea salt. Broadening their offerings makes sense, if only as a way to get people who’ll shell out for steak seasonings to start noticing Jacobsen salts. I take a pinch of the steak seasoning and sprinkle it onto my tongue. It is indeed good—a pleasing mix of black pepper, garlic, and red pepper flakes—but before leaving headquarters, I stop by the store for something else. What I really want is a bag of the flake.

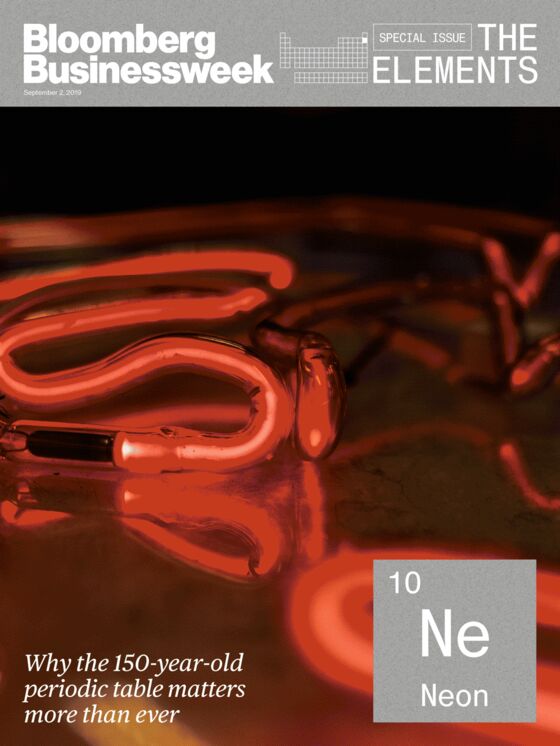

This story is from Bloomberg Businessweek’s special issue The Elements.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Silvia Killingsworth at skillingswo2@bloomberg.net, Jim Aley

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.