Jack Welch Remembered by Businessweek’s Former Executive Editor

Jack Welch Remembered by Businessweek’s Former Executive Editor

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The telephone call came unexpectedly on a Sunday night in early March 2002. Jack Welch was on the line, his raspy voice as familiar as any I had ever heard. After all, I had spent a full year with him, more than 1,000 hours face to face, helping to write his memoir, Jack: Straight From the Gut, published almost six months earlier.

As was typical of Jack, the legendary chief executive of General Electric Co. who died on March 1 at the age of 84, he got to the point quickly. He wanted me to know the Wall Street Journal would publish a story the following morning that would disclose a personal relationship he was having with the editor of the Harvard Business Review.

What came next was even more surprising than his revelation. “If in any way you’re disappointed in me, I want to apologize to you,” he said. “I want you to know that the story is true. I fell in love, and I don’t want you to feel betrayed in any way.”

Of course I didn’t. I already knew his second marriage was in trouble, and I would never judge two people who had clearly fallen in love. This was the Jack Welch I had come to know and respect. It was Jack, straight from the gut. In that call, he was deeply human and openly accountable, willing to own up to the painful consequences of his actions.

The obituaries faithfully chronicle GE’s nearly fivefold rise in revenue and soaring market value that made it the most valuable company in the world under his leadership from 1981 to 2001. What they often fail to fully capture is the real-life figure who was my friend. He was wickedly intelligent, with a dogged curiosity that combined a deep intellect with street smarts. He was laugh-out-loud funny, never turned his mind off, and squeezed every precious moment out of every day. And he was never short of opinions or perspective. After I obtained a leadership role in one editorial operation, for instance, he mentored me on how to cautiously deal with a powerful superior. “He’s a snake,” Jack told me, “and he’s the worst kind of snake: He’s a smart one.”

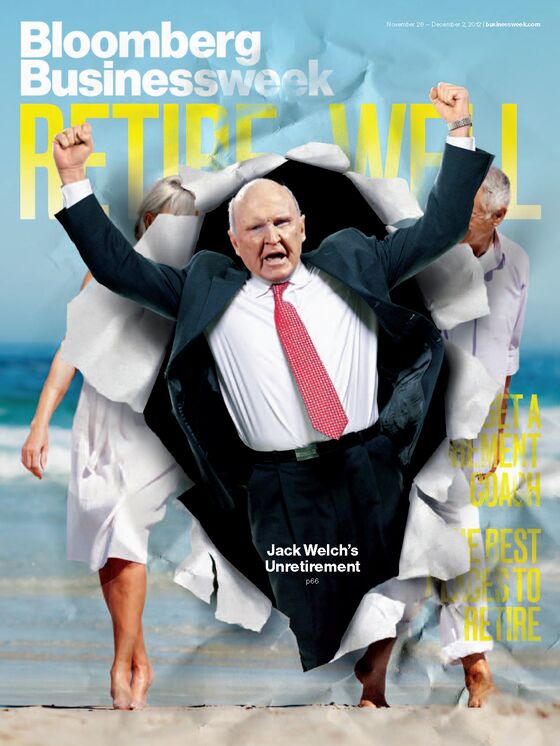

Contrary to many accounts, Welch didn’t seek the limelight and was never comfortable in it. It took me almost a year to persuade him to sit for the on-the-record interviews for a BusinessWeek cover story I wrote in 1998. Two years later, that story would lead to our book collaboration as Welch approached his last year as CEO. Our relationship never really ended. Shortly after becoming executive editor of BusinessWeek in 2005, I asked Jack and his new wife, Suzy, to write a weekly column. It quickly became one of the magazine’s most read features.

Throughout the year working with him on the memoir, the goal was to create an intimate conversation between Jack and the reader, a dialogue that might occur at a bar over a drink. Jack insisted that there could be nothing in the book that might be considered “pompous” or “preachy.” He wanted to address the small and big mistakes of his career, from his acquisition of Kidder Peabody to hiring Japanese employees on their ability to speak English. If anything, he was tough on himself—but drew a line when it came to hurting someone else’s feelings or reputation. He didn’t want a book that settled scores or dished dirt.

It wasn’t easy to work closely with Jack. He was the most demanding and relentlessly challenging person I ever met. We fought over what to include and what to omit. He sometimes grew frustrated with my reluctance to change a draft, one time reminding me that it was his book and he would damn well decide what he wanted in it.

We went through every draft, word for word, comma for comma, over and over again. During one of our sessions that led to hundreds of changes scribbled on every white space of the manuscript, Jack grabbed my arm, looked me in the eye, and said, “You’re going to f--- this up, aren’t you?” I laughed. What else could I do? It was Jack being Jack.

There were tender moments as well. Jack grew misty-eyed recalling the night he washed his mother’s back in a hospital room, hours before her death in 1965. And he was hilarious in recounting the details of his heart attack in 1995 that led to bypass surgery. (He dashed through a crowded hospital emergency room at 1 a.m., jumped on an empty gurney, and began shouting: “I’m dying! I’m dying!”)

But Jack became most animated when reflecting on the ideas that formed the core of his management philosophy. We explored the origins of many, from the dictum that a company be No. 1 or No. 2 in every business it remained in to the concept of a “boundaryless” organization. (The word came to him on a beach in Barbados when a guy dressed up as Santa Claus popped out of a submarine.) Those ideas, among others, made him one of the most influential—and sometimes controversial—corporate leaders of the 20th century.

It’s a rare week when I don’t think about or remind someone of what Jack taught me. To a friend considering dismissing a poorly performing employee, I recently repeated Jack’s insistence that anyone who is fired should never be surprised, and it’s a manager’s responsibility to make sure an employee knows his performance is wanting. And I’m continually reminded of his beliefs that people always trump strategies and that hiring the best people and giving them what Jack called “stretch assignments” was also a responsibility of leadership. That’s why he considered GE not a conglomerate operating in multiple businesses, but a people factory. Those ideas and many more have stood the test of time.

Jack’s passing has brought much commentary on his legacy, his many accomplishments, and his perceived flaws. Yet what I remember and admire most are not the results of the corporation he so smartly led, but the extraordinary, imperfect human being behind it—the man who called late one night to offer an unneeded apology to a friend.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.