Italy Borrows From Mississippi With a Program to Help the Poor Find Work

Italy Borrows From Mississippi With a Program to Help the Poor Find Work

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Luigi Di Maio’s anti-establishment Five Star Movement won a surprising electoral victory in March 2018 after promising to give poor Italians a “citizens’ income” and a path into the workforce in a country with perennially high unemployment.

The €7 billion ($7.7 billion) program, aimed at people earning less than €9,300 a year, is under way with the help of 3,000 workers who act as both coaches and social workers. The navigators, as they’re known, have been hired, trained, and embedded in Italy’s often understaffed and underfunded network of 550 public job centers. They’re tasked with providing services ranging from résumé preparation to liaising with potential employers.

“Today, a revolution in the labor sector has started, and we’re putting a fundamental link in the system—the navigator,” Di Maio, the leader of the Five Star Movement, said at a kickoff training session in Rome in July.

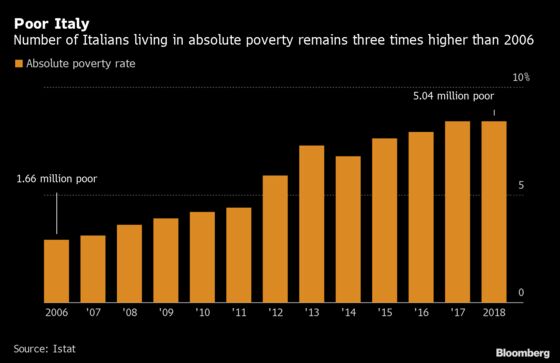

Italy’s navigators may have one of the toughest jobs in the euro zone. Just over 5 million Italians—about 8% of the population—live in poverty, according to the national statistics institute. That number is three times higher than in 2006, before the economy succumbed to a double-dip, five-year recession.

The unemployment rate in Italy, the bloc’s third-largest economy, stood at 9.5% in August, compared with 3.1% in Germany and 8.5% in France. Adding to the bleak outlook, Italy’s long-term jobless rate—those who’ve been unemployed for 12 months or more—is among the highest in Europe.

It took about a year to get Di Maio’s welfare and employment program off the ground, partly because Five Star’s ally to win the election, the anti-immigrant League, was a lukewarm backer. After the populist governing coalition collapsed in August, Five Star remained in power, having found a new political partner in the Democratic Party. That means the policy is likely to survive the country’s tumultuous politics for the foreseeable future.

Di Maio recruited Domenico Parisi, a 53-year-old Italian data scientist who teaches sociology at Mississippi State University in the U.S., to head Italy’s National Agency for Active Labor Policies (Anpal), which oversees the job centers and navigator program. (Di Maio was deputy premier and economic development minister when the navigators started their training and is now foreign minister in the current government.) “What this is really about is linking people left out of the workforce and putting them in touch with the labor market,” says Parisi, speaking with an accent from his native Puglia region mixed with a distinct Southern U.S. drawl, in an interview in his Rome office.

Parisi moved to the U.S. after graduating from Milan’s Catholic University and earned master’s and doctoral degrees in rural sociology and applied statistics from Pennsylvania State University. In Mississippi, he used his data expertise to start a research center focused on the labor force, and he developed the Mississippi Works mobile job-search app. Parisi says he’s advised two Mississippi governors, incumbent Phil Bryant and his predecessor, Haley Barbour, on how to reduce unemployment by using tools such as artificial intelligence and high-performance computing.

“In Mississippi, we were able to convince employers we had a valid workforce,” Parisi says. “We can do the same thing in Italy.” While Mississippi’s jobless rate has fallen in the last five years, it’s still one of the highest in the U.S., at 5.2%.

Parisi’s cheerleading, team-building approach was on display this summer at a kickoff meeting of navigators on the island of Sardinia. The conference opened with the Queen song We Are the Champions and closed with We Will Rock You. His rah-rah style has been parodied on television by one of Italy’s most popular comedians and been the subject of front-page newspaper stories.

Davide Tritapepe, a 37-year-old Italian with experience in banking, marketing, and information systems in three countries, says he decided to become a navigator after finding himself unemployed. In April he competed with thousands of others for the €30,000-a-year navigator job. “I understood what it meant to be unemployed, and I wanted to do something useful that would help people in need,” says Tritapepe, who had to pass a 100-question multiple-choice test before being selected to work at a job center in the northern city of Brescia.

Labor experts have cast doubt on whether the navigators project can have an impact, citing challenges with combining welfare assistance and job recruitment. Claudio Lucifora, a labor economics professor at Catholic University, estimates that two-thirds of recipients of the citizens’ income may not be qualified to work “and are more in need of social services.” While the navigators program is a “good idea on paper,” Lucifora says, it will be tough to make it effective.

Some European countries such as Germany have done well with similar programs because they have adequate government agencies equipped and funded to provide a range of services, says Maurizio Del Conte, a labor law professor at Milan’s Bocconi University and Parisi’s predecessor at Anpal. “To build such a system in Italy, you need more time and resources with a longer-term view,” Del Conte says.

Local politics have slowed the project’s start. In the southern area of Campania, the region’s governor has held up approval for the program because he doesn’t agree that the navigators are needed in the job centers (the remaining 19 Italian regional governments have given their go-ahead). Parisi says various obstacles facing the program will be overcome. His biggest challenge, he says, is cultural. “In Italy, there’s an attitude that you’re defeated before you’ve started. We have to change that mentality. Italy has to adjust to a modern labor market. There isn’t any choice.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rebecca Penty at rpenty@bloomberg.net, Cristina Lindblad

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.