An Israeli Startup Sells Panic Buttons to U.S. Synagogues

An Israeli Startup Sells Panic Buttons to U.S. Synagogues

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Yoni Sherizen’s startup has grown from two employees to seven in the past three years, he’s close to sealing his biggest deal to date, and investors value the business at $13 million. Yet every time he signs up a customer, he worries about the tragic cost of success.

His company, Gabriel—named after the horn-blowing archangel—helps protect places such as community centers and synagogues from attackers. “Unfortunately, bad news brings a lot of attention to a product like ours,” says Sherizen, a 41-year-old American-born rabbi who lives on a kibbutz in central Israel. So far, all of Gabriel’s customers are Jewish groups in Florida, Michigan, and New Jersey concerned about anti-Semitic violence, and Sherizen hates the idea of profiting from shootings and the fear they spawn. “I wrestle with that all the time,” he says.

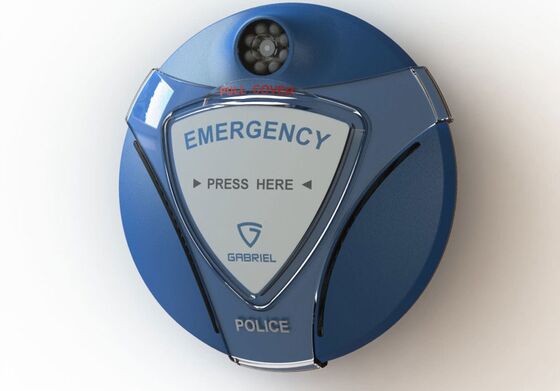

Gabriel’s sole product is a hardware and software package that includes panic buttons to be placed around a site, each with a fisheye camera that gives police and security managers a view of the scene. Community members can download a mobile app that has its own alert button, so they can send real-time updates on escape routes or safe places to hide. The price starts at $10,000 a year for 10 devices and associated services.

Sherizen says he eschews the “fearmongering” of some security companies, avoiding images of mass shootings in his marketing and instead highlighting the sense of safety a customer might find. “The security industry is full of really tough characters and sometimes unsavory personalities,” says Sherizen, who spent 15 years working for nonprofit organizations before founding Gabriel together with Asaf Adler. “We’re trying to take the scariness out of it.”

But fear is inevitably what sells such products. Ramapo, a town with 90,000 Jewish residents 30 miles north of New York, had been in talks with Sherizen for months. After three attacks on Orthodox Jews in the metropolitan area last fall, “panic set in,” says Mona Montal, chief of staff for the town’s supervisor. Ramapo is poised to install Gabriel’s system at more than 200 locations—synagogues, schools, and banquet halls—serving more than 50,000 people, which would represent a sevenfold expansion of the company’s sales. “I hope we never use it,” Montal says on her way to an event honoring the police officers who intervened in a stabbing spree at a nearby rabbi’s home in December.

Last year the U.S. saw 400-plus mass shootings in which four or more people were injured. That’s boosted demand for improved security in public places, with revenue in the business on track to grow 52% by 2025, to $61 billion globally, researcher MarketsandMarkets predicts. Dozens of companies have jumped in, providing everything from bulletproof backpacks and hoodies to full-time monitoring systems. Rave Mobile Safety and Alertus Technologies offer panic-button software similar to Gabriel’s. Avigilon, a unit of Motorola Solutions Inc., sells video and surveillance equipment. Athena Security says it can program cameras to detect hundreds of types of guns and immediately alert police if they sense a threat. “The market is ripe for good products,” says Noel Glacer, head of a security industry recruitment firm, whose son was a student at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., when a gunman killed 17 people there two years ago. “I tell people, if you think it won’t happen to you, that’s what I thought. And then it did.”

A key part of Sherizen’s service is training for an emergency. While testing its system at new installations, Gabriel conducts drills that help students, teachers, and other community members understand what to do in a shooting and give administrators a chance to familiarize themselves with the equipment and software. Gabriel’s network also addresses a frustration for police: Most Orthodox Jews avoid sites such as Twitter and Facebook for religious reasons, but that’s where authorities typically post emergency updates. Rabbis have deemed Sherizen’s app appropriate for their followers.

Sherizen got the idea for the company in 2016 after a pair of Palestinian gunmen attacked a Tel Aviv restaurant, killing four people. The same year he started Gabriel, now based in a suburb of Tel Aviv, with backing from friends and relatives. Today he’s negotiating for $3 million in funding from new investors as he seeks to move beyond the Jewish community, pitching his product to schools, churches, mosques, malls, nightclubs—anyplace people gather. “We chose the name Gabriel because it’s cross-religious,” Sherizen says.

The fear that’s driven Gabriel’s growth almost destroyed the company. After the October 2018 shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, which claimed 11 lives, Sherizen gave a series of interviews in which he identified his first customer. The leaders of that community were furious, concerned that he’d effectively issued a challenge to anti-Semites to beat their defenses, he says. He immediately apologized and asked journalists to scrub mentions of the name. “I have to safeguard my customers’ interests,” Sherizen says. “They are a target for a lot of people.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.