Iran’s Millennials See Windows to the Outside World Closing

Iran’s Millennials Are Worried About Losing Social Progress

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Ashkan Gomrokian is a young man who’s easy to find. Most afternoons he’s in the skate park in downtown Tehran, perfecting his crooked kickflip and lipslide. The commonplace scene would’ve been considered deviant in Iran a few years ago. Gomrokian, 26, recalls once getting dragged off to a police station and accused of being a satanist. He says authorities still don’t like his skater tribe much—“the oversized clothes, the hair, the tattoos”—but the Tehran municipality has built multiple dedicated skateboard spaces in the past few years, part of an effort to beautify the city and make it more livable.

People in Tehran celebrated the 2015 multinational nuclear agreement the way another city might mark a major sports victory. Thousands of young Iranians took to the capital’s streets, some dancing to electronic house music, an unthinkable scene a couple decades ago. In their lifestyles and aspirations, Iran’s youth likely have more in common with their global peer group than any generation of Iranians since the revolution.

The administration of U.S. President Trump nonetheless says its hard-line approach is intended to bludgeon Iran into becoming a “normal” country. Trump last year decided to pull the U.S. out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, colloquially known as the Iran nuclear deal, putting its future in doubt. As America and its partners in the Middle East step up pressure against the country, the doors to the outside world are closing again. Gomrokian gives a small example from his skateboarding life: “Your shoes get ripped, your board cracks, you need to buy new gear regularly,” he says. As the country again became more isolated and the rial tumbled, prices for the imported boards rose; after the U.S. imposed harsh new sanctions last year and ordered the world to follow suit, he says, no boards are coming in at all.

While authorities in the 40-year-old Islamic Republic can still view expressions of individuality as defiance, they’ve been forced to accommodate the younger generation’s push to engage with the wider world. Well into the 1990s, for instance, pop music was forbidden in public and European and American CDs had to be smuggled in. Now Iranians such as Nesa Azadikhah can make a career out of performing it.

Azadikhah, 35, says she got interested in electronic music as a teenager. A few years ago, there were only a handful of Iranian artists dabbling in the form, but the scene has expanded enough for Tehran to host a major festival last year. “It’s not like we go on the beach and do raves,” Azadikhah says. She puts on audiovisual shows at gallery openings and product launches and runs the online platform Deep House Tehran, which promotes the work of local DJs and electronic music composers. She’s keen to engage with her peers abroad, connections that could be threatened if the West continues closing doors against Iran.

Curbs on social life and public entertainment remain widespread in the mostly Muslim Middle East. What reform has occurred has been mostly top-down: In nearby Saudi Arabia, for example, the absolute ruler has decided outdoor concerts are now acceptable. In Iran, with its conservative religious hierarchy but more active civil society, each step toward progress has been fiercely contested.

The struggle is typically framed with President Hassan Rouhani, a proponent of social reform, on one side and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who holds the orthodox line, on the other. Rouhani won two elections on a millennial-friendly pledge to loosen up. “The way youngsters see life and the world is different,” he told his cabinet last year. He’s delivered on some promises, including backing widespread access to fast internet connections, which has helped facilitate the flow of information, and allowing local tech entrepreneurs to launch businesses.

But Rouhani pinned his hopes on the nuclear deal. Since Trump’s election, he’s lost ground to Khamenei and other hard-liners who see a Western “cultural war” against Iran, while the country’s regional rivals blasted Rouhani’s attempts at diplomacy as duplicitous. The economic optimism of 2015 has given way to rising unemployment, inflation, and sporadic protests. While the remaining parties to the agreement—including France, the U.K., and Germany—introduced a financial mechanism in January to allow for trade to continue despite the return of U.S. sanctions, companies are unlikely to expose themselves to the risk of losing American business. Iran has said it will stay in the deal only if it derives sufficient benefits.

With some Trump officials backing regime change, and Iran’s government tightening the reins to quell any opposition that might be fueled by outside influence, the tension inside the country is growing. Meanwhile, society continues its push toward greater openness. One 2018 case was particularly revealing: A teenage girl was arrested and forced to express public remorse after posting a series of videos that showed her dancing seductively without wearing a headscarf, in clothes that didn’t conceal the shape of her body. Until a few years ago, a woman wouldn’t think of sharing any snippet of her private life online, and certainly not in a public forum. But the outcry on TV and in some op-ed pages wasn’t all directed at the girl. Many commentators slammed the government for wasting time on such a trivial offense while the economy was suffering.

Iran’s provincial towns can feel like a different world, even if they’re just a couple of hours from Tehran by train. Mehdi Bahrami, a 27-year-old pharmacist in nearby Zanjan, says his leisure options are limited. There’s little theater or music, and his 13 million rial ($113) monthly salary won’t stretch to cover a gym membership. Nevertheless, change has arrived here, too. Bahrami spends much of his free time sipping tea with relatives, but he says he’s also developed deep friendships on social media, where he discusses history, philosophy, and Iran’s future with contemporaries all over the country.

And he sees social shifts within his middle-class family. A few years ago, he’d get grief from his mother for seeing a girl, Bahrami says. “The other day, I saw my sister, who’s seven years younger, getting a chat message with a guy’s name. I asked her, ‘What’s this?’ And my mum snapped back: ‘I’m aware, no need to say anything,’ ” he says. “I said, ‘Well, that’s interesting, when I was her age you’d have given me hell!’ ”

Twitter is banned, but Iranians find workarounds and use it to complain about ministers and their policies. In August hundreds joined the #where_is_your_kid? campaign, asking the ruling class to come clean about their family privileges, such as sending their children to study or live abroad or securing appointments to state-linked positions. Even senior officials felt obliged to respond, including Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, who was quoted in Iranian media saying that his two children were both privately employed in Tehran.

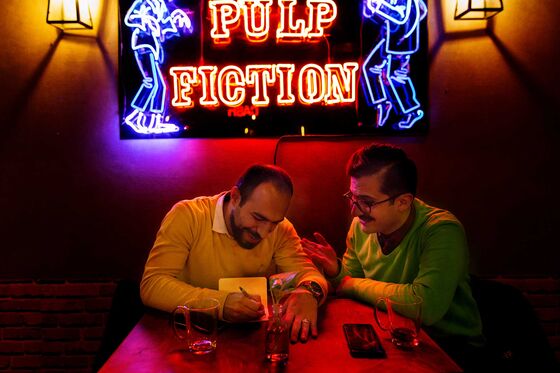

In April 2018, the authorities banned Dubai-based Telegram, Iran’s most popular messaging app, asking that people use local alternatives. For millions of young Iranians, it was like losing a lover—or so it seemed to video producers Human Najafpoor, 31, and Pejman Takdehghan, 28, who responded with an original, broken-hearted ballad called A Love Song for Telegram. A video they recorded of the song showed them sitting under a tree, clinging tight to a framed Telegram logo and occasionally bursting into tears. It’s been shared 1.2 million times across multiple online platforms.

The friends had begun experimenting with comedy music videos after meeting at a startup accelerator in Tehran. They formed a band called Dasandaz, which means both “speed bump” and “joke.” They’ve been able to monetize their talents, providing music for commercials, including one for the Iranian version of Airbnb and another for a food-delivery app. Their work isn’t intended to be political, but it sometimes pushes boundaries. “Even in this closed environment,” Najafpoor says, “we’re able to say some of the things we want to express.” Like others interviewed, they don’t see themselves as activists, just people trying to pursue their interests—ideally while earning an income. But even the youthful Dasandaz singers, both born well after the revolution, no longer feel like they’re in the vanguard. “The younger generation is freer,” Takdehghan says. “One day you look around and realize how much has changed.”

The collapse of the rial as the world anticipated new U.S. sanctions, followed by the economic impact once they took effect, has spoiled one young woman’s dreams. Niloufar, who asked to be identified only by her first name to maintain her privacy, is a devotee of parkour, a high-intensity sport born on military obstacle courses. Practitioners run, climb, and leap at walls, using them to vault through the urban landscape. Her first hurdle, though, was at home, winning drawn-out fights with her parents.

“It was considered something a street girl would do, like being a drug addict,” she says. But parkour has caught on. Now some gyms even offer it for women, and Niloufar makes about 6 million rials ($53) a month teaching. The 28-year-old can’t afford to move out of her family’s house, but she saved enough to travel by land to neighboring Turkey last May for her first international competition. Niloufar says the trip will likely be her last for a while. “My dream is still to compete, but because of Iran’s situation, I don’t think it can happen,” she says. “The money I’d set aside to buy a car is now worth nothing.”

Living standards in Turkey and Iran—majority-Muslim neighbors with similar populations—used to be about the same. During Iran’s sanctions decade, Turkey surged ahead. It’s now a destination for disillusioned young Iranian expats. Gomrokian, the skateboarder, knows that in other countries some skilled peers can make a living out of their hobby. He’s limited to local contests with a few dozen participants at best and no prize money. “We know we won’t get anywhere,” he says. “But we still train, so that maybe the next generation of skateboarders can.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Ben Holland

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.