Investors Are Sick of Waiting for GE’s Desperately Needed Reboot

Investors Are Sick of Waiting for GE’s Desperately Needed Reboot

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- General Electric Co.’s 126-year-long story is one of survival by reinvention. While many of its contemporaries have flamed out or merged away their identities, GE has remained a household name and a symbol of corporate America. But these rebirths had side effects, and those are now behind GE’s greatest crisis since the Great Recession.

On Oct. 1, Larry Culp became just the 12th chief executive to lead the industrial conglomerate that traces its roots to Thomas Edison. He arguably has the hardest job of them all. GE stock had collapsed by more than 50 percent in the year leading up to his abrupt appointment, and it’s fallen more than an additional 30 percent since; on Dec. 4, it closed at $7.28. Some GE bonds have traded at junk-like levels amid doubts over the company’s ability to manage its debt load. Culp must sell assets to raise funds, restore credibility to GE’s earnings reports, and create a mix of businesses with the potential to not only survive his turnaround efforts but also thrive over the long term. And—perhaps most important—he has to act quickly, because investors’ patience is wearing thin.

Slumping demand for gas turbines and a yearslong push to shrink the company have eroded GE’s industrial cash flow. Meanwhile, a surprise $15 billion reserve shortfall disclosed in January at a legacy long-term-care insurance business effectively shut off the cash spigot from the GE Capital finance arm. That’s undercut GE’s ability to bear what analysts estimate to be $100 billion in net liabilities after accounting for potential added cash needs at GE Capital, including a bigger-than-expected hole in the insurance business. JPMorgan Chase & Co. analyst Steve Tusa in November cut his share price target to $6—a level last seen in the early 1990s, when Jack Welch was at the helm.

Welch was both revered and hated for uprooting the company’s jobs-for-life culture with his relentless pursuit of higher profits and industry dominance. That mentality, mimicked with less success by his replacement, Jeff Immelt, is what allowed the recent downturn in the power market to become such a catastrophe for GE. The company prioritized scale over discipline and was overly optimistic about demand trends for too long. There’s no better example than Immelt’s poorly timed $10 billion purchase of Alstom SA’s energy assets in 2015. GE took a $22 billion writedown in its power unit in this year’s third quarter, mostly because of that deal. The business booked a $631 million operating loss in the period, and GE says it’s too uncertain of that division’s trajectory to update its 2018 cash flow and earnings guidance.

The power business’s relative importance has grown in recent years. After wrong-way bets at GE Capital forced Immelt to cut the dividend for the first time since the Great Depression, he attempted to revitalize the company by refocusing on its industrial core. This led to the divestiture of NBCUniversal, completed in 2013, and an accelerated wind-down of GE Capital starting in 2015. But with those sales went much of the cash flow supporting GE’s partially rebuilt dividend. A later pivot into industrial software soaked up plenty of cash with little to show for it. Cutting GE’s quarterly dividend was one of the first orders of business for John Flannery after he replaced Immelt as CEO in 2017.

Flannery had the unpleasant but necessary task of laying GE’s shortcomings out in the open. The $15 billion reserve shortfall disclosed in January was the first sign management may not have a handle on the company’s liabilities. The hole was multiples of the $3 billion benchmark management had discussed just a few months earlier and was a stunning gap in a business that supposedly had been stress-tested every year. Then came the Oct. 1 announcement that GE would write down substantially all of the goodwill in its power unit. That eroded what was left of management’s credibility; Flannery was ousted that same day, after just 14 months in the job.

Now, it’s Culp’s turn in the dunking chair. He was beloved as Danaher Corp.’s CEO for his impressive track record of buying and improving businesses. But he never had to deal with the kind of debt squeeze he faces at GE. Culp appears to have taken criticisms of Flannery’s lack of aggressiveness to heart. In about his first two months on the job, he cut GE’s quarterly dividend again to a mere penny per share and accelerated the sale of GE’s stake in Baker Hughes, the oilfield-services company with which it merged its energy assets in 2017. GE could hardly have picked a worse time to start selling Baker Hughes shares, with the stock near its lowest levels since the deal. But it was a testament to Culp’s resolve and temporarily sated investors’ need for action. Culp is also splitting up the power unit to speed operating improvements, with one business focused on the troublesome gas turbines and services unit and another dedicated to healthier parts of the market such as grid solutions.

Still, Culp’s decision to appoint a trio of insiders to lead the new power units raises concerns about his willingness to make radical cultural changes. He’s still learning how to handle his higher profile at GE, with his public comments doing more to unsettle than soothe investors. His waffling on the possibility of selling GE shares and GE’s recent shift into attack-dog mode over negative analyst reports seem misplaced until Culp lays out a more comprehensive turnaround plan, expected in early 2019.

For GE to begin the healing process, investors need to know how bad things are. This starts with setting 2019 targets GE can actually hit after years of big misses, but it’s also about providing transparency on the company’s liabilities. Higher-than-expected costs from U.S. tax reform and the outcome of a U.S. Department of Justice investigation into GE’s WMC subprime mortgage business are among the possible factors that could force the company to funnel additional funds to GE Capital beyond the $3 billion it’s already committed to for 2019.

Furthermore, that reserve shortfall in GE’s long-term-care insurance business may get bigger under new accounting rules set to take effect in 2021 that mandate the adoption of a standardized discount rate and require companies to update liability calculations each year. A shareholder lawsuit alleges GE improperly managed reserve assumptions for the long-term-care business and fraudulently pulled forward revenue tied to product service agreements; GE denies these accusations. Former employees quoted in that lawsuit have been interviewed as part of a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission investigation into GE’s accounting practices, the Wall Street Journal reported in late November. The Justice Department is also investigating.

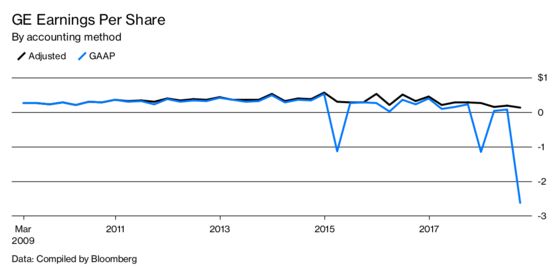

Reducing the adjustments to GE’s chosen earnings metrics will send a strong message that the company’s reporting issues are behind it. GE reported 49¢ in adjusted consolidated earnings per share over the first nine months of 2018, vs. a $2.50 loss based on generally accepted accounting principles. A big swing factor there is the goodwill charge, but even excluding that, GE’s metrics fail to reflect its underlying free cash flow and business fundamentals.

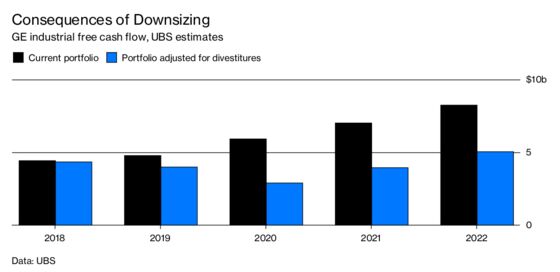

Next, Culp has to decide how he’s going to bring the debt load down. Flannery announced divestitures of $20 billion in assets, including a merger of GE’s transportation unit with rail equipment manufacturer Wabtec Corp. and sales of a health-care IT business and the distributed power operations. In June he proposed selling a 20 percent stake in GE Healthcare, a big maker of medical imaging and monitoring equipment, and spinning or splitting off the rest to investors. Sticking with that plan—combined with a full drawdown of the Baker Hughes stake for an estimated $16.9 billion—should give GE a path to cutting its net industrial leverage in half by the end of 2020, to about three times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, says UBS Group analyst Steven Winoker.

Even at that reduced level, GE’s leverage would be higher than that of peers with similar credit ratings. And added liabilities at GE Capital would undercut this math and take away funds from debt reduction. GE has said it’s looking at options to offload the long-term-care insurance business, but it would likely need to pay heavily to get someone to take the assets off its hands.

That lack of wiggle room may prompt Culp to consider bigger changes. He’s already said he may instead sell as much as a 49.9 percent stake in GE Healthcare to raise cash. He could also carve out GE’s life-sciences operations from the health-care business and sell those on their own. UBS’s Winoker has estimated life sciences could fetch at least $21 billion—with Culp’s old company Danaher as one possible buyer. But that could take away the assets with the best growth prospects, undermining the appeal of the standalone health-care business.

Another option is to divest GE’s aircraft leasing operations. It’s considered the crown jewel of the remaining finance assets, although the value of its portfolio came under scrutiny in late November after competing helicopter lessor Waypoint Leasing Holdings Ltd. filed for bankruptcy. GE has pushed back on comparisons between Waypoint and its Milestone Aviation arm. Fleet utilization is about 90 percent at Milestone, GE says, compared with about 78 percent at Waypoint. Barclays Plc analyst Julian Mitchell in October estimated GE’s aircraft leasing assets in total could fetch more than $10 billion in a sale. GE also likely has other smaller businesses stashed within its main units that it can sell. In particular, the reorganization of the power division may set up divestitures of the less-challenged parts of that business.

Taken together, GE probably has enough levers to pull that it can scrape by. But it will be a long, painful process, and the big question for investors is what will be left once Culp is done. The current plan is to transform GE into an aviation, power, and renewable-energy company. Gas and wind turbines are essentially jet engines by another name, so there’s technological overlap here—but longer-term this isn’t an ideal combination. Both power and aviation are longer-cycle capital-intensive businesses that are vulnerable to economic downturns. The irony of GE’s crisis is that it’s happened at a time when industrial companies writ large are doing well. That won’t last forever.

So eventually GE will need to untether the aviation business from the ugly stepchild power unit. One radical option is a combination of the aviation unit with Honeywell International Inc.’s aerospace division. That would provide opportunities for cost cuts to mitigate the squeeze Boeing Co. and Airbus SE are putting on suppliers and offer an answer to United Technologies Corp.’s recent $30 billion takeover of avionics maker Rockwell Collins Inc. But to consider aviation deals from a position of offense rather than desperation, GE first needs to get its house—and, most important, its debt—in order.

Sutherland is a deals columnist for Bloomberg Opinion.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.