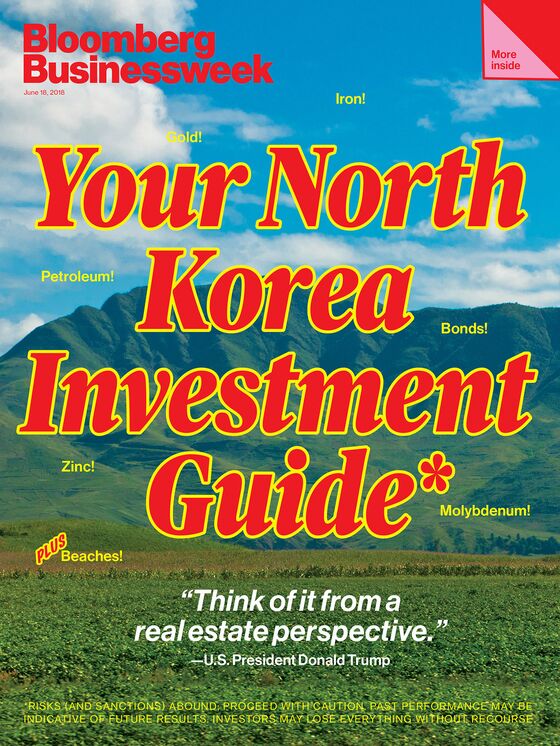

Investing in North Korea Is Not for the Faint of Heart

The U.S. realtor-in-chief sees oceanfront condos and a turnaround play. Others see a money pit.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Would any corporate executive in his or her right mind be willing to put big money into a centrally planned economic underachiever? One that’s best known for food shortages, a backward manufacturing sector, and woefully inadequate infrastructure?

Maybe a businessman whose name adorns buildings in such places as Azerbaijan, Panama, and the Philippines. On June 12, Donald Trump wrapped up an historic summit with Kim Jong Un with a plug for North Korea’s waterfront. “They have great beaches,” America’s realtor-in-chief said at a news conference. “You see that whenever they’re exploding their cannons into the ocean. I said, ‘Boy, look at that view. Wouldn’t that make a great condo?’”

Pristine coastline isn’t North Korea’s only untapped asset. The country boasts vast stores of minerals—including iron and rare earths—which could be worth $6 trillion, according to a 2013 estimate by the North Korea Resources Institute in Seoul. There are also unconfirmed reports of oil and gas deposits in the East and West seas. Then there’s North Korea’s working-age population of about 17 million, another potential asset in the eyes of businesses in Japan, South Korea, and China, where labor forces are graying and shrinking. “Northeast Asia could become one of the most exciting places in the world,” says Masaaki Kanno, chief economist at Sony Financial Holdings Inc.

All this bounty has been largely off-limits to foreign companies since 2006, when the United Nations began layering on economic sanctions as punishment for North Korea’s efforts to build a nuclear arsenal. Net inflows of foreign direct investment amounted to just $93 million in 2016, compared with $12 billion for South Korea.

To some, North Korea is still the ultimate frontier market, a place with extra-large opportunities—and similarly sized risks. (Mind you, the country has no stock exchange or publicly traded companies, so it’s not designated a frontier market by investment banks.) “North Korea is now where China was in the 1980s,” says Jim Rogers, whose Rogers Holdings Inc. doesn’t currently have investments in North Korea. “It’s going to be the most exciting country in the world for the next 20 years. Everything in North Korea is an opportunity.”

That may be, but the country is also littered with foreign deals that have gone wrong. Sweden, for instance, is still awaiting payment for 1,000 Volvo sedans shipped in the 1970s. A Chinese mining company called its four-year venture in the isolated nation a “nightmare.” And an Egyptian telecommunications giant doing business there can’t repatriate its profits. “A major deterrent to foreign investment is the chronic breakdown in the rule of law,” says J.R. Mailey, an investigator who’s worked on fraud and corruption cases in North Korea.

Surprisingly, some who’ve butted heads with the regime in Pyongyang remain upbeat about the country’s prospects. Orascom Telecom Media & Technology Holding SAE, an Egyptian company, helped build the North’s communications networks after entering the country in 2009. But its Koryolink business lost exclusive rights to the market after Kim rose to power in 2011 and financed the rollout of a rival cellular network. “The emergence of a state-owned competitor and the strict economic sanctions made our operation much less attractive,” an Orascom spokeswoman says. But she adds, “The lifting of sanctions and peace between the two Koreas will improve the overall business climate in the DPRK and will have a positive impact on Koryolink.”

Investors from China, North Korea’s economic patron, have also been burned. Xiyang Group signed a contract in 2007 to set up a venture with the government to process 500,000 tons of iron ore per year. Five years later, Pyongyang terminated the deal and cut off the plant’s access to water, electricity, and communications. Xiyang issued a terse statement after it didn’t receive a cent of compensation.

Andrei Lankov, a director with Korea Risk Group, which provides clients with information and analysis on North Korea, sees a pattern in the way companies such as Orascom and Xiyang have been treated. “Once they see foreign businesses get too profitable, the authorities just take a bigger slice,” he says.

Lankov is doubtful that, even if international sanctions were lifted, Kim’s regime would lay out the welcome mat for foreign businesses. “Openness would be suicidal for the regime, as it would bring in a flood of information from outside and could loosen its political control,” he says. Consequently, he says, North Korea would limit international companies to joint-venture projects as minority partners.

The bulk of any new investment would likely come from companies south of the border. Conglomerates including Hyundai Group, Lotte, and KT already have set up task forces to look into business opportunities in the North. In a recent survey by the Korean Federation of SMEs, 96 percent of the 101 South Korean companies polled expressed interest in returning to Gaeseong, an industrial park in North Korea that was closed in 2016 because of military tensions.

“It took us about two years to break awkward moods and to get along with North Korean workers,” says Shin Han-yong, who runs Shinhan Trading, a maker of fishing nets that was one of 124 companies operating in Gaeseong. Still, he’d like to expand his business in North Korea if the complex reopens. Says Shin: “The only thing I can do now is watch Trump’s mouth.” —With Sohee Kim, Daniele Lepido, Chris Anstey, Serene Cheong, Ben Bartenstein, Rachel Chang, and Tomoko Yamazaki

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net, Daniel Ten Kate

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.