Instacart Hounds Workers to Take Jobs That Aren’t Worth It

Instacart Hounds Workers to Take Jobs That Aren’t Worth It

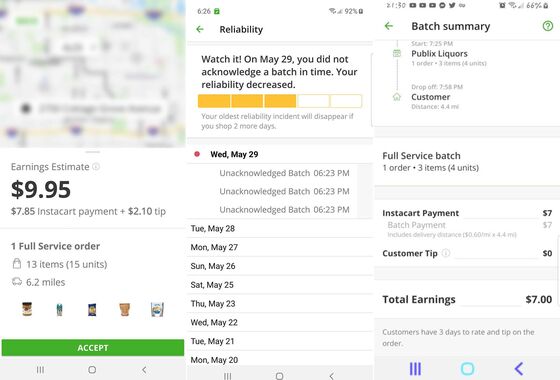

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When Instacart’s eponymous grocery delivery app gets a new order in, it typically alerts a nearby “full-service shopper,” its term for the worker who gathers and delivers the groceries, by sending the order to the worker’s phone with a bright green “ACCEPT” button and a repetitive pinging sound. But even if that shopper—who ostensibly has the flexibility to reject a gig—decides the latest one isn’t worth the time and effort, the on-demand food delivery platform usually doesn’t offer an option to decline.

Workers are forced to entirely mute their phone, close the app, or sit through about four minutes of that strange pinging, which many say sounds like a submarine’s sonar and some compare to a time bomb. Those who wait it out sometimes wind up having to do it all over again when the same job pops back up in their queue. To avoid that, people often take jobs they didn’t want, says Buffalo, N.Y., Instacart worker Eric Vallett, who has tapped ACCEPT more than once to avoid another series of pings. “You just want to get away from that sound,” he says.

The four-minute sonic barrage is among a slew of tactics Instacart uses to push workers to handle low-paying tasks they otherwise might reject, according to interviews with dozens of shoppers. They say the company has hounded them with phone calls, text messages, and threatening in-app messages, and that it quietly but explicitly punishes them for rejecting undesirable tasks by limiting their gig options and income. “We should have a right to say ‘I don’t want it’ without being penalized,” says Theresa Thornton, who shops for Instacart in Missouri City, Texas.

How much Instacart controls its shoppers isn’t just a matter of morale or public relations—it’s an existential question. Like Uber, Instacart’s classification of workers as contractors means they don’t enjoy the protections and benefits employees get. The company’s business model centers on keeping costs low enough to satisfy investors and keeping deliveries swift and reliable enough to win over customers, without exerting the kind of clear management authority that might lead a court to rule that the app’s shoppers are employees and therefore covered by laws like minimum wage.

An Instacart spokesperson, who declined to be quoted directly, says the four-minute wait ensures workers have time to make a decision about whether to accept the task, using the info Instacart provides on the number of items, retailer, distance, and estimated earnings involved. The company wants to provide workers the best experience it can, she says, and they can mute the sound by muting their phones.

Workers say Instacart isn’t really providing the sort of flexibility it advertises. The company reserves many of its jobs for people who sign up ahead of time to be available during particular shifts. To get substantial work through Instacart’s app, shoppers say, they need to earn “early access” to the shift signups by working 90 hours over the prior three weeks, or 25 hours over the prior three weekends. And that privileged status can be threatened if workers turn down jobs, or “batches,” they deem undesirable. They say Instacart may prematurely end their shift or add a “reliability incident” to their profile, which hurts their chances of getting the better work. Instacart says it doesn't require workers to work at particular times, that most workers select hours without getting early access, and that many appreciate that the reward system offers them a goal to pursue.

One in-app message Instacart has sent workers warns them to “Watch it!” because their “reliability decreased” when they failed to “acknowledge a batch in time.” Another tells workers who chose not to accept a batch that to continue shopping they should confirm in the app that they are available, and that “Not doing so may affect your future ability to select hours for services.” In Washington state, Instacart worker Ashley Knudson says she was punished with a reliability incident even after she’d told the company she was stopping work for the day because her car had been broken into and was full of glass. “It’s certainly not flexible,” she says. The app does prompt workers to explain why they rejected an offer. The possible explanations it offers include the batch being too big or small and “other,” but not insufficient pay.

Instacart says reliability incidents are meant to make sure they offer work to shoppers who are available, not to punish them. The app may assume a worker who rejects four consecutive batches is idle and end their hours for the day and give them a reliability incident, Instacart says, but the worker can avoid that if within 30 minutes they re-enter the app and resume shopping. Workers who believe they’ve been wrongly given an unreliability incident can contact support staff to get it removed, and the company says it will do so in cases like car trouble or illness. The reliability incidents go away over a 30-day period and don’t lead to workers being permanently banned, according to Instacart, which is also testing a version of the early access system based on customer reviews of a worker’s deliveries rather than hours worked.

Beyond the app, workers say, waiting the requisite four minutes to dodge an offer they don’t want can trigger an automated text message to their phones that says “Your batch has been removed.” Every so often, Instacart’s “Shopper Happiness” staff calls to push them to handle a certain batch. “They’ll call you repeatedly. They’ll be like, ‘You’re the only shopper available,’” says Kristin Klatkiewicz, an Instacart worker in Covington, Wash. “Sometimes they’re like, ‘You need to take this order.’ ” She says she’s offered to take low-paying jobs in exchange for an extra five bucks and been flatly told no. Sherri Cliburn, an Instacart worker in Sarasota, Fla., says Shopper Happiness has repeatedly called to say “I want to talk to you about the order that you’re taking” regarding orders she hadn’t actually agreed to take.

Instacart says a bug recently caused its app to send workers text messages when they did not accept a task, rather than in-app notifications, and that it has fixed that bug. The company says that absent extenuating circumstances, its support staff shouldn’t be contacting workers unprompted, and it doesn’t force anyone to take on unwanted tasks.

This spring, Instacart released an “on-demand” feature that it said would make its app more accessible and flexible for workers by making some tasks available to whoever logs on in a certain region, not just people who’ve signed up for those particular hours. But some workers who’ve tried it say the on-demand system pushes down their earnings and makes it tougher for them to figure out what’s worth their time. The tasks are offered simultaneously to a bunch of workers in the same area and assigned to the first person who accepts them, so usually at least one is willing to gamble—often within seconds, with no time to read the offer carefully. “It’s like Hunger Games,” says Instacart worker Heidi Carrico in Portland, Ore. “If you don’t accept it, someone else will.” Ryan Calo, a law professor at the University of Washington, says such systems are “designed to be manipulative and coercive.”

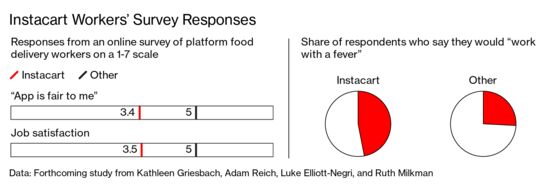

“Instacart seems to demand that workers behave like employees, but they have none of the benefits of employment,” says Kathleen Ann Griesbach, a research fellow at Columbia’s Interdisciplinary Center for Innovative Theory and Empirics and author of a forthcoming study of app-based food delivery work. According to the study, which received funding from the United Food & Commercial Workers union, Instacart workers reported working about 32 hours a week and earning an average of $13.09 an hour after expenses, $9.50 of it from Instacart and the rest from tips. (The federal minimum wage is $7.25 an hour, or $2.13 for tipped workers.) Instacart says its data show that three-quarters of the more than 100,000 workers on its app work less than 10 hours a week.

Instacart, which was valued last fall at $7.9 billion and is eyeing an eventual initial public offering, has weathered a series of controversies about its worker pay practices. In 2017, while denying wrongdoing, it agreed to pay $4.6 million to settle a lawsuit brought by workers claiming they were wrongly tagged as contractors, and to adjust its user interface so customers wouldn’t get confused between actual tips and the optional “service fee” that the company could pocket itself. Instacart has also been criticized for paying some workers less money because of tips they were promised by customers, which workers said amounted to stealing their tips; earlier this year the company said it would cease this practice. It also said it would begin paying a minimum of $7 to $10 per batch its workers gathered and delivered, depending on region.

Since last year, Instacart and its peers have been lobbying officials for relief from a new threat to their business model: a ruling by California’s Supreme Court dictating that workers can’t be considered contractors under the state’s wage law unless the work they’re doing is outside of a company’s usual course of business. Like Uber, Lyft, Postmates, and DoorDash, Instacart has been meeting with labor leaders and politicians to lobby for a legislative compromise that would let it avoid reclassifying its workers as employees. The company says it’s working with lawmakers and other relevant parties to modernize laws and maintain flexibility and choices for workers.

“The way these platforms have been allowed to develop has allowed the creation of this fiction that algorithms are distinct from management systems,” says David Weil, the dean of Brandeis University’s social policy and management school and former head of federal wage and hour enforcement under President Obama. “The system that Instacart has created bears little resemblance to one composed of independent contractors,” he says, and “in almost every respect looks like employment.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeff Muskus at jmuskus@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.