Index Funds Are King, But Some Indexers Are Passive-Aggressive

Index Funds Are King, But Some Indexers Are Passive-Aggressive

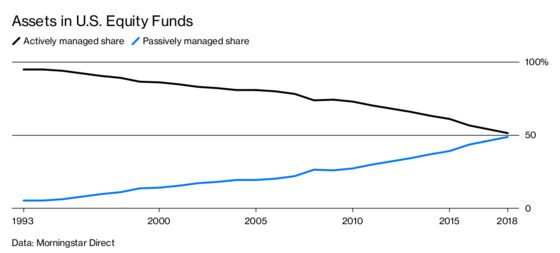

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Vanguard Group founder Jack Bogle, who died on Jan. 16 at age 89, ushered in an era of low-cost investing for the many. He launched the first index mutual fund for individual investors at the end of 1975 for the purpose of passive investing: Skip the stockpicking, save on fees, and simply ride the ups and downs of the overall market. His fringe idea has become mainstream. Sometime this year, analysts at Morningstar Inc. say, assets in passively managed U.S. equity funds are likely to surpass assets in actively managed ones. By pushing down fees across the industry, Bogle may have saved American investors $1 trillion over his lifetime, calculates Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Eric Balchunas.

Bogle theorized that you can’t reliably beat the market, so you might as well join it and settle for average performance. So far, so good: Through August, only 17 percent of actively managed funds in the U.S. “large blend” category had beaten the performance of their passive peers over 20 years.

Something peculiar has happened along the way, though. Today, much of the investing that’s tied to indexes is passive in name only. Investors in many index funds aren’t content to go with the flow like rubber ducks on a river. Instead of trying to beat the market by picking stocks, they’re trying to do it by picking indexes. They’ve been aided in this by the rise of exchange-traded funds, which now hold $3.5 trillion in assets in the U.S. Most ETFs are considered passive because their managers don’t have discretion in choosing stocks, but they’ve allowed investors to bet on almost every conceivable sector, asset type, and geographic region. (Bogle called ETFs “a bastardized form” of index funds on a Bloomberg podcast last year.)

According to the Index Industry Association, more than 3.7 million indexes exist—and though most don’t have funds tracking them, it goes to show how flexible the idea of passive management has become. “Indexes have mutated into a form of what they’ve long been used to judge: active management,” Ben Johnson, director of global ETF research for Morningstar, wrote in a column on Jan. 18.

“Smart beta” funds are another way investors are becoming less passive while still taking advantage of the cost savings and automaticity of indexing. Instead of holding shares of companies in proportion to their market value, a smart beta fund holds them in proportion to some other measure such as sales, dividends, or book value. The goal, again, is to beat the market—this time by exploiting factors that seem to help investors outperform over time, such as having a low stock price in relation to book value. It used to be that only stockpickers tried to do that. Smart beta funds have more than $800 billion under management, according to the website ETF.com.

There’s been a “Cambrian explosion of new species” of index-related strategies, including ones that replicate various hedge fund strategies or that suppress volatility by moving more assets into cash when markets get rocky, Andrew Lo, a finance professor at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, wrote in a 2015 paper called What Is an Index? Such products, he wrote, have “blurred the line between passive and active.”

The rise of index funds isn’t only changing the asset management business; it could also be having an effect on how public corporations are managed. Index fund managers have more incentive to push for improvements in corporate governance than an active investor does, because they generally don’t have the option to bail out of a stock when they don’t like the way executives are steering a company. Among other things, passive managers appear to prefer board members to be independent of management. “A 10 percent increase in ownership by passive investors is associated, on average, with a 9 percent increase in the share of directors on a firm’s board that are independent,” according to a 2014 paper by Todd Gormley, Donald Keim, and Ian Appel, all then at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

Activism by fund managers isn’t necessarily a good thing—say, if the managers use their influence to suppress competition. Near the end of his life, Bogle expressed concern over academic research theorizing that consumers could be harmed by the rise of index funds and other kinds of funds that own big stakes in companies that compete with one another. One study appeared to find that airfares rose more on routes where the competing airlines had high levels of cross-ownership by funds.

Last year BlackRock Inc., the world’s biggest fund manager, which manages index funds as well as actively managed ones, warned in a filing that its “business operations, reputation or financial condition” could be adversely affected by policies to address possible harm from institutional investors’ common ownership. The Federal Trade Commission is taking the concept seriously enough that it held a daylong workshop on it at New York University Law School on Dec. 6.

One proposed remedy is to limit a fund to a maximum of 1 percent of the shares in competing companies. If it wanted to go above that threshold, it would have to own shares in just one company in the sector. That would spoil the business model of big index fund companies—and no doubt upset a lot of fund investors. (It’s also not clear what difference it would make, because company managers would still know that the underlying fund investors are diversified and own shares in competitors.) Yale School of Management professor Fiona Scott Morton says she doesn’t expect any action soon but adds, “Someday we might have an administration that was pro-competition.”

The case against funds isn’t proven yet, though. Critics of the airline study say its results are hard to interpret, in part because of frequent airline ownership changes and bankruptcies. A study of the four companies that dominate the breakfast cereal market in the U.S. found that the companies behaved opposite from what the antitrust theory would have predicted, according to one of the authors, Christopher Conlon of New York University’s Stern School of Business. Answers Yale’s Morton: “We’re watching evidence accumulate. It’s a little bit slow.”

Such questions arise only because of the popularity of index investing. Bogle, who started the whole thing, was both proud and on the lookout for trouble. In an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal in November, he wrote, “The question we need to ask ourselves now is: What happens if it becomes too successful for its own good?”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.