Antitrust Regulators Ask Whether Index Funds Deserve More Scrutiny

Antitrust Regulators Ask Whether Index Funds Deserve More Scrutiny

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Since index funds became widely available in 1976, they’ve upended the business of money management and made investing for the masses easier and cheaper. They’ve also had an unexpected side effect: Because they’re so large, index fund families are among the top shareholders in many companies, including those that compete with one another. Despite this, funds’ share purchases get no review from antitrust regulators.

That could change under an initiative by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission—possibly radically. Two proposals could result in investments by all the giant mutual fund families coming under scrutiny for the first time from both the FTC and the U.S. Department of Justice, which share antitrust enforcement. It’s the index funds that appear to be causing regulators the most heartburn. Just three companies—BlackRock, Vanguard Group, and State Street—manage about 80% of all indexed money, and together their portfolios own more than 20% of the typical S&P 500 company. The Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund just became the first stock fund to hit $1 trillion in assets.

Some antitrust enforcers and academics believe that common ownership—when one institutional investor is the largest holder of shares in companies in the same industry—is subtly tamping down the competitive forces that motivate companies to gain market share by innovating and lowering prices. In theory at least, an owner of rival companies would generally prefer they don’t compete forcefully, as doing so can eat into profits. For example, a 2018 study found that, when the same institutional investors are the largest shareholders in branded drug companies and generic drugmakers, the generic companies are less likely to offer cheaper versions of the brand-name makers’ drugs.

It’s an idea that not so long ago was on the fringes of antitrust debates. But it’s become more prominent along with index fund companies’ growth and increased concern among policymakers about monopolies. The funds don’t have to notify regulators in advance of acquiring a large number of shares in a company, as is required of other kinds of investors, such as activist hedge funds waging proxy battles to gain control.

The FTC proposals might end that exemption. “It’s untenable to assume we don’t need notice of acquisitions where either one firm or the same firms own individually or in the aggregate a significant percentage of the voting shares of competitors,” says Bilal Sayyed, the director of the FTC’s Office of Policy Planning, who initiated the proposals.

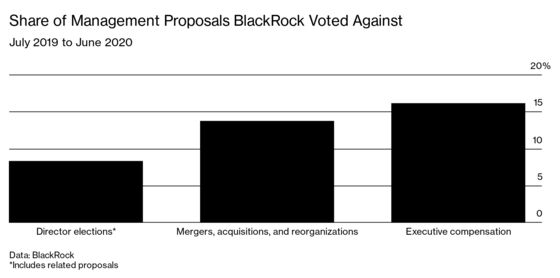

One potential change could require fund families to report their aggregated holdings to the government, giving regulators more insight into the level of common ownership. The bigger worry for fund companies is buried in a separate, pre-regulatory notice in which the FTC asks for public comment on whether mutual funds should lose their filing exemption because they engage in a broad range of activities that fall under the label “shareholder engagement.” These activities include communications from funds that nudge portfolio companies to hold the line on executive pay, lower carbon emissions, increase workforce and board diversity, and meet other goals they consider part of good corporate governance. Fund companies today point with pride to such efforts.

Mutual funds’ current antitrust-reporting shield, dating to 1978, was based on the idea that they bought shares solely for the purpose of investment and paid scant attention to how companies were managed. “The exemption is pretty narrow, and it’s hard to see [how] what the institutional investors are doing fits into the exemption,” Sayyed says. In one of its notices on the proposals, the FTC says a discussion about executive pay could turn into one about how performance should be measured, delving into the basic business decisions of a company.

The fund companies say engagements are just part of taking care of their clients’ money and dispute the possibility that their ownership is harming competition. Tara McDonnell, a spokeswoman for BlackRock Inc., says it’s still analyzing the proposals. “Our investment and stewardship activities are guided by our fiduciary obligations,” she says. A State Street Corp. spokeswoman says that index funds save investors money and that the proposals “could have a significant impact on index products and other types of investment funds and their investors without a clear benefit.”

Regulatory review could make operating an index fund more complex. In cases where companies have to notify regulators of share purchases, the agencies can request more information, and more time, to determine if the deal might harm competition. “They ought to limit outright the amount these companies can own, but at least a review is worthwhile, because it gives the commission a hook to ask” if ownership is too concentrated, says Graham Steele, a senior fellow at the anti-monopoly group American Economic Liberties Project. He published a paper in November describing the fund companies as part of a new “money trust.”

The proposals are in the early stages and could change, and what happens next may depend on the views of President-elect Joe Biden. The FTC won’t vote to scrap or advance either proposal until a public comment period ends in February, after the inauguration. The Trump-appointed chairman of the FTC, Joe Simons, is expected to leave, and the rest of the commission will be split evenly between Republicans and Democrats until he’s replaced. But the politics of antitrust don’t break down on predictable party lines—there’s been growing interest in the issue on the Left and the Right.

Index funds could eventually find themselves caught between the demands of environmental, consumer, and civil rights groups, which want them to be more accountable for the behavior of companies they own, and regulators who may see activism as a reason to end their filing exemption. In a twist, another part of the FTC’s proposals would relieve activist funds from having to report acquisitions of 10% or less of a company, so long as they don’t also hold more than 1% of a competitor. But without a review exemption, the 1% rule could snag index funds, which often hold more than that in rival companies. The upshot is that index funds could have less flexibility than those controlled by corporate raiders.

Read next: The FTC’s Antitrust Case Against Facebook Stakes Out New Ground

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.