In Donald Trump vs. Jay Powell, New Battle Lines Are Being Drawn

In Donald Trump vs. Jay Powell, New Battle Lines Are Being Drawn

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Stoicism, the classical philosophy of emotional resilience, logic, and virtue, has long been a handy guide for anyone dealing with a crazy boss. Seneca the Younger, a first-century Roman statesman, found it helpful in managing the famously volatile Emperor Nero. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell also seems to be a fan. He has a mantra, a simple phrase he uses frequently in private and occasionally in public, that sounds straight from the stoic’s guide to a happy life: “Control the controllable.”

For a full year, Powell has been on the receiving end of an unprecedented barrage of abuse from President Donald Trump, who’s called the Fed “loco,” as well as “the biggest threat” facing the U.S. economy. This from the man who tapped him for the job. Powell enjoyed five quiet months at the helm of America’s central bank after he took over from Janet Yellen in February of last year. But as he and his colleagues ratcheted up borrowing costs, the president’s ire rose. Trump took his first shot last July, and things only got worse as the Fed plowed ahead with four interest rate hikes over the course of the year, the last in December as officials also penciled in two rate hikes for 2019. That, along with the global economy already showing signs of strain, sent financial markets into a temporary tailspin, further inflaming the president.

That’s when Trump began asking aides about his ability to oust the Fed chief in discussions reported by Bloomberg News on Dec. 21. Advised that he doesn’t have the authority to fire Powell outright, the president asked White House lawyers in February to explore whether he could strip him of his chairmanship, a legally dubious move that could lead to a messy court battle. After Bloomberg News reported this twist, Trump claimed on June 23 that he has the power to demote Powell.

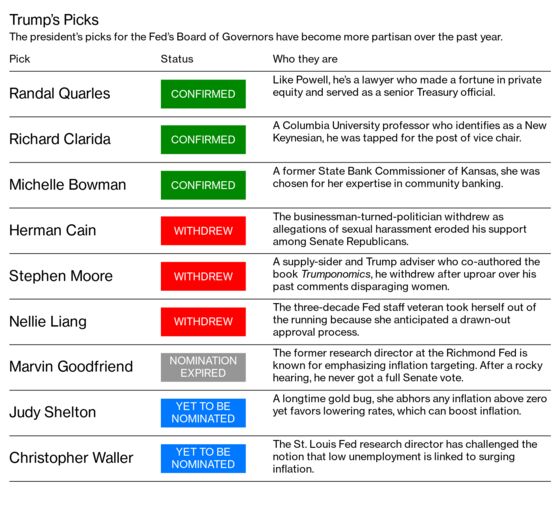

During this period, the president’s assault on the Fed took a turn. He’d already filled three openings on the bank’s seven-member Board of Governors and elevated Powell to the top job, picks that were well received inside and outside the institution. Clearly disappointed with their performance, however, he then began a concerted effort to fill two additional openings with individuals who would toe his line on interest rates. Candidates interviewed for the governor job this year have been asked whether they would support a rate cut if they were on the board now, according to two people familiar with the meetings.

According to one senior insider, Trump’s effort to pack the Fed has spooked the central bank’s staff and leadership far more than his public rantings. At the very least, it could drag partisan politics straight into the central bank’s closed-door meetings on monetary policy. Worse, it could pose a more elemental threat to the institution.

Judy Shelton, a former economic adviser to Trump who’s among his latest central bank picks, is the embodiment of all these fears. In the same way that the president’s choices to lead the Environmental Protection Agency and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau have sought to undermine the missions of those agencies, Shelton could bring a level of iconoclasm rarely, if ever, seen at the Fed.

In the meantime, even an end to rate hikes hasn’t bought Powell any peace. By January he was backing away from further tightening as market turmoil continued. A majority of Fed officials then shelved projections for 2019 rate hikes in March as the risks of a worldwide slowdown mounted, in large part because of uncertainty caused by Trump’s trade war. That’s when the president pivoted and began beating the drum for rate cuts. The economy would be “like a rocket ship” if only Powell & Co. heeded his call and began easing monetary policy, he said this month.

Trump isn’t the first American president to bully his Fed chair. Lyndon Johnson summoned William McChesney Martin to his Texas ranch in 1965 for a tongue-lashing during which, according to one account, he shoved him while yelling, “Boys are dying in Vietnam and Bill Martin doesn’t care.” Richard Nixon’s staff planted a false story about former Fed chief Arthur Burns wanting a pay raise as they pushed him for low rates in the runup to the 1972 election.

Former Chairman Paul Volcker revealed in his recent memoir that in 1984, Ronald Reagan ordered him, through chief of staff James Baker, not to raise rates. Yet since Bill Clinton, U.S. presidents have, at least publicly, left the Fed alone in deference to its independence. Trump, desperate to keep the economy purring and the stock market soaring, has laid waste to that tradition.

Ironically, he may have made it harder for the Fed to give him what he wants, because Powell and the rest of the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee don’t want to be seen as caving to the president’s demands. That’s the very reasoning President Clinton’s economic team used in the 1990s to convince him that pressuring former Chairman Alan Greenspan would be counterproductive. “If the case is clear that they should cut, they will cut,” says David Wilcox, who joined the central bank in 1986 and retired late last year as head of its critical research and forecasting unit. But in this atmosphere, he adds, “when the Fed eases, the evidence would have to be just a little bit stronger.”

It’s looking increasingly likely, even if there’s a higher hurdle, that Trump will get his wish when the FOMC meets on July 30-31. After trade and manufacturing continued to show signs of weakness, and the rock-solid jobs market suffered a hiccup, Powell signaled in June that the case for a cut had strengthened. He continued pointing in that direction when he testified before Congress last week, despite a strong June jobs report. Powell even admitted the Fed may have overtightened rates by underestimating certain fundamental shifts in the U.S. economy.

Some in Washington have begun to wonder whether Powell might crack under the pressure of the almost daily invective, perhaps even throw up his hands and quit. “Inconceivable,” says David Rubenstein, co-founder of the Carlyle Group, where Powell was a partner from 1997 to 2005. “He’s not a person who just walks away from things. He’s a very tough person, and I think he’s got the right personality for this.”

Rubenstein is far from alone in that view. In interviews with Bloomberg Businessweek, several former colleagues said they were certain Powell would continue to shrug off Trump’s barbs and remain focused on his job.

Indeed during his testimony to Congress last week, Powell fielded a question about whether he would leave if Trump called to fire him. His answer, he said, would be no.

The 66-year-old, Ivy-educated lawyer has spent more than two decades working in Washington, during which time he’s developed a granite exterior. He also built himself a multimillion-dollar fortune in the private equity business before shifting to government work in 1990 after a mentor, Nicholas Brady, was named secretary of the Treasury. After another stint in the private sector, Powell, a registered Republican, joined a think tank, the Bipartisan Policy Center, before President Barack Obama appointed him to a seat on the Fed in 2012.

Powell was a governor for six years, earning the respect of fellow policymakers and the bank’s army of brainy economists because of his studious and thoughtful commitment to work. Along the way, he’s also won a reputation for keeping his cool. “In some people, it’s just their nature to be straightforward and not get flustered,” says G. William Hoagland, senior vice president at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

In 2011, Hoagland and Powell helped talk Congress into raising the debt ceiling to avert a default on U.S. debt that could have been disastrous for financial markets, the dollar, and the economy. Hoagland recalls accompanying Powell to see a lawmaker who claimed a default could be managed by prioritizing which debts would be paid in such a scenario. “Jay listened, and then in a calm way told him his position would be a nightmare,” he says. “I’ve never seen him get upset, even when he had a good reason.”

That doesn’t mean Powell has been entirely passive in the face of his tormentor. Although he’s carefully avoided a direct clash with Trump, he’s made it clear the Fed won’t cave to political pressure when setting rates, something which would be tantamount to a moral failure in Powell’s book. “We’re human. We’ll make mistakes,” he told an audience in New York on June 25. “But we won’t make mistakes of integrity or character.”

Powell has also worked to cultivate allies in Congress, the Fed’s real boss. He’s made good on his 2018 pledge to “wear the carpets of Capitol Hill out,” holding almost 150 meetings or phone calls with legislators since becoming chair, according to his public calendar through May.

His pilgrimages to Capitol Hill appear to be paying off. Several Republicans have voiced support for him in recent months. Pennsylvania Senator Pat Toomey told Bloomberg TV on July 10 that Powell was doing “a great job.” Asked how he would view any attempt by Trump to remove the Fed chief, Toomey responded: “I think that would be a very, very bad idea.”

While the president’s criticism of the central bank generates headlines, there’s no hint that it’s disrupted the way Powell and the rest of the staff go about the business of crafting monetary policy. This is an intensely focused—some would say notoriously insular—organization. Its circadian clock is set to the calendar of FOMC meetings, of which there are eight a year. Each cycle features an intense preparatory process aimed at developing policy proposals that can be defended before a roomful of macroeconomic experts. Political views are taboo. Gut calls don’t cut it. “If one of them has a strong view and they can’t articulate it, they’re not going to get anybody else to go with them,” says Nellie Liang, former director of the Fed’s Division of Financial Stability. Liang was nominated to serve as a Fed governor by Trump in September, but she withdrew her name in January, saying a prolonged confirmation process would leave her “in professional limbo for too long.”

The bank has a culture that puts a premium on professional competence and breeds a fierce loyalty to the institution. It’s not that the Fed never screws up: Ben Bernanke is viewed, with only some exaggeration, as having saved the world, but he also missed the subprime mortgage bubble that made saving the world necessary. Still, the staff and leadership approach their work convinced that no one else is likely to do better, not because they’re smarter, but because they have no agenda other than getting policy right. It’s a quality that comes across as valiant to their allies and self-righteous to critics.

After more than seven years at the Fed, Powell is thought to be as loyal to those ideals as anyone in the building. A decision to up and quit would constitute a mammoth betrayal. “What would cause deep and long-lasting damage is if Jay were to step down and some person was nominated whose only credentials were their political partisanship,” Wilcox says.

In 2016, with two seats open on the Board of Governors and Chair Janet Yellen’s term set to expire in 2018, that fear emerged as soon as Trump won the presidency. For a while, however, his nominations proved a pleasant surprise. Although he shunted aside the widely respected Yellen, he made entirely conventional choices in promoting Powell and in tapping Richard Clarida as vice chair and Randal Quarles as vice chair for banking supervision.

But the profile of Trump’s picks has changed now that Lawrence Kudlow, director of the National Economic Council, has assumed full control of the process of identifying potential nominees for the president’s approval. On the outs is Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, who championed Powell’s candidacy for the chair, though insiders say he still retains indirect influence through Kudlow.

Kudlow, a Wall Street analyst-turned-TV personality, struck out with his first two choices this year. One was his friend Stephen Moore, a fixture of conservative think tanks and a lifelong advocate of supply-side economics. The other was Herman Cain, a businessman who briefly ran for the Republican Party’s presidential nomination in 2018. Neither was coy about suddenly advocating for lower rates under Trump. However, their loyalty to the president couldn’t compensate for an assortment of personal and professional shortcomings that presaged a difficult confirmation process. Both withdrew their names before being formally nominated.

Kudlow’s latest picks are safer bets. Christopher Waller, research director at the St. Louis Fed, has decidedly dovish views on monetary policy that are in sync with Trump’s. Nonetheless, his status as a Fed insider and his long record of academic work explaining his views pretty much guarantee the respect of his colleagues on the FOMC.

Shelton, whose selection was revealed in a Trump tweet on July 2, is something altogether different and potentially troubling to anyone who believes in the established conventions of central banking. Best described as a libertarian intellectual and author, she’s been affiliated with various free-market think tanks, including the Hoover Institution and the Atlas Network. She joined Trump’s campaign in August after writing an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal that lauded him for targeting currency manipulation and unfair trade practices by China. The president later named her the U.S. envoy to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Shelton is a hardcore inflation hawk who in past years has advocated for a return to the gold standard. In the absence of a gold standard, targeting superlow inflation generally means calling for high interest rates—certainly higher than they are now. But since it first emerged that she was being considered for a Fed job, her views on rates have changed. In May she told Bloomberg News she wouldn’t do anything to threaten the president’s pro-growth agenda. Last month she went further, telling the Washington Post that as a Fed governor she would seek to lower interest rates “as expeditiously as possible.”

Asked about the apparent flip-flop, Shelton said in an email that her comments on lowering rates were directed “specifically at the mechanism through which the Fed carries out its interest-rate targeting decisions.” That’s a reference to the Fed’s practice of paying interest on bank reserves. Shelton says that policy incentivizes banks to park their money at the central bank instead of channeling it into new loans.

Throughout her career, Shelton has been a passionate advocate for the concept of “sound money.” In this view of the world, the stable value of the currency is a moral imperative and should be fixed to a unit of measure, like a weight in precious metal. This makes her far more than a hawk in dove’s clothing. It suggests she rejects the very notion that a central bank ought to modulate the supply of credit in an effort to smooth the booms and busts that can wreak havoc in an economy.

On that count, Shelton pleads both guilty and innocent. She readily admits to questioning long-held assumptions about the connection between monetary policy and economic growth. “I would welcome the chance to challenge the status quo at the Fed,’’ she said in an email. While she denies that her objective is to curb the Fed’s role in taming the economy’s ups and downs, she questions whether central banks have succeeded in achieving this goal by setting benchmark interest rates. “That task is better performed through the interaction of free markets in determining the cost of capital,’’ and not, she says, by “a small group of officials meeting in Washington, D.C., every few weeks.’’

Alan Blinder, a former vice chairman of the Fed, says the central bank can manage an apostate on the Board of Governors without much disruption. “It’s possible that a very eccentric member of the board could be accommodated, and so what?” Blinder says. “She would be intellectually isolated.” But given Trump’s disdain for Powell, Shelton would, if confirmed, represent a potential chair-in-waiting. One administration official familiar with the matter told Bloomberg in July that’s an option once Powell’s term expires, or even before.

If promoted to the top job, Shelton could tip the institution upside down. “I’d like to think that’s an unthinkable outcome,” Blinder says. “We’ve never had an open rebellion against a chair of the Fed. You have the potential, should this happen, to have an open rebellion.”

There are two paths to that still unlikely scenario. In one, Trump wins reelection and waits out Powell’s four-year term before nominating Shelton, by then a governor, for the chair. In the second, he moves to demote Powell after Shelton is confirmed as a governor. Unsurprisingly, Sherrod Brown, the Ohio senator who serves as the ranking Democrat on the Senate Banking Committee, has blasted her candidacy, saying she’s unlikely to get any Democratic support. “She is singularly unqualified,” he says. “She’s far too political. She brings into question the independence of the Fed.” Democrats would need at least four Republican senators to join them in rejecting Shelton, however, putting Powell’s relations with Congress to a test.

The second scenario could lead to entirely uncharted territory. If Trump were to demote the current Fed chief, Powell could challenge the move in the courts. The Federal Reserve Act, which established the central bank in 1913 and set out the rules governing it, doesn’t explicitly protect the chair from demotion, but Powell could make a solid case against his unilateral removal by the president. “There’s an argument there, but it’s murky and untested,” says Deepak Gupta, founding partner of Gupta Wessler PLLC in Washington, who specializes in appellate and Supreme Court litigation. “It’s anyone’s guess how that would come out if there were an actual court challenge.”

The odds of such a crisis appear low for now. Congress will probably recess for the summer without holding hearings on the Shelton and Waller nominations, and a rate cut in late July could quiet Trump, at least temporarily. But come autumn, the Fed could face dangers it never imagined. What counsel might Seneca have for Powell? This bit of wisdom from the Roman sage seems appropriate: “To bear trials with a calm mind robs misfortune of its strength and burden.” —With Saleha Mohsin and Laura Litvan

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net, Margaret Collins "Peggy"

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.