Inequality Is Holding Economies Back. Education Could Be One Solution

If America Can’t Fix Education, It Won’t Beat Inequality

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Anyone who believes the system is rigged would have experienced a grim “told you so” moment on March 12, when federal prosecutors charged 33 parents who’d bought into a scheme to ensure their children spots at elite universities. Those implicated included an Oscar-nominated actress, a co-chairman of international law firm Wilkie Farr & Gallagher, and the former chief executive of Pimco. Their alleged crimes were as varied as conspiring to fix test scores, bribing coaches, and falsifying athletic records. What they all had in common was wealth.

The Twitterati crowed, non-wealthy students lamented, and for once both sides of the political spectrum were in agreement: The sweeping indictment underlined how deeply unfair U.S. higher education has become. Success in the modern economy often seems to be more an accident of birth—hinging on family income bracket and connections or the student’s race and gender—than a reward based on individual ability and achievements. It’s an impression that cuts deep, given how crucial education is to economic mobility.

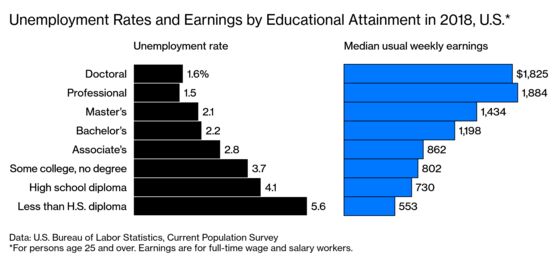

College attainment is a decent proxy for a shot at the good life, at least in the U.S. Four-year graduates earn about twice as much per week as high school dropouts and have better health outcomes. Research by the late economist Alan Krueger, who died on March 16, showed that some of that benefit may come from college attendees’ better starting positions in life. Non-Hispanic white adults are almost 60 percent more likely to have graduated from a four-year college than their black counterparts, Census Bureau data show. The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education finds that nearly 90 percent of high school graduates from affluent families enroll in college, vs. 60 percent of kids in the bottom quarter of income.

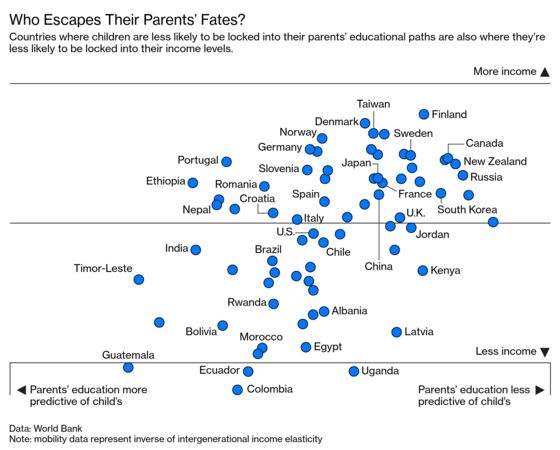

Outside of education specifically, unequal access to opportunities is a global story. Barriers vary by country, but children are generally more likely to earn incomes similar to their parents’ in nations with higher income inequality. The graph of this relationship is often called a Great Gatsby Curve, first introduced by Krueger and named after F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel about social mobility and its costs. Kids in Panama and Madagascar, where income is very unequal, are more likely to stay poor if they’re born poor. In countries where earnings are fairly evenly spread, such as Denmark and Finland, they’re more likely to be masters of their own fates.

America is further toward the high-inequality, high-immobility end of the scale than other advanced economies. Such stickiness leads to a problem International Monetary Fund economist Shekhar Aiyar calls “talent misallocation.” When high-aptitude people are shunted to the margins of society, “not only is it unfair, it’s also bad for growth,” he says. As Aiyar describes in a February paper, countries with high income inequality paired with low mobility see slower economic progress.

Higher income inequality goes hand in hand with lower upward mobility in America, research by Harvard economists Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and others has shown. “It just speaks to this kind of question: To what extent are we a country where kids have this notion of the American dream?” Hendren says. “What can we do to improve it?”

Both Jonathan Greenberg and Tyrell Jackson graduated high school with big dreams of working in music—Greenberg as a professor, Jackson as a performer. They’re imperfect analogues, but their stories demonstrate how different life can look depending on the world you were raised in.

Greenberg, who’s 43, grew up in an affluent suburb of Boston, the high-achieving son of two white parents. His father is a physician. If there was ever a question around college at his private high school, it wasn’t whether he would go but where? Brown University was Greenberg’s answer, and his parents paid his tuition in full.

“I didn’t even really think twice about studying humanities in college,” he says. He graduated with degrees in music and philosophy—and without debt, which he doesn’t hesitate to acknowledge was a privilege. “I was able to pursue things I wanted to pursue without thinking about the implication of college loans.”

He worked relatively low-paying but résumé-padding jobs. After a Fulbright-administered teaching gig in Austria, he pursued a fellowship-funded Ph.D. in musicology from the University of California at Los Angeles. He later earned a second master’s, in library science, from the City University of New York at Queens College. Today, he and his wife both hold full-time, salaried jobs and are raising their 9-year-old son in Queens. He’s not rich, but he has a good work-life balance and feels like he’s making a contribution. “I don’t think of it just in terms of making money.”

Jackson, 31, grew up in New Jersey, the black son of a single mother who hadn’t graduated college but held down a decent job. Lacking guidance and familiarity with the higher-education system, he enrolled in a community college musical theater program after graduating high school. “I felt like I was swimming in deep water,” he says.

He was living with family and working at a restaurant in Newark’s airport to support himself, commuting an hour and a half from home to get there. Getting from work to school took another hour. Not long after classes started, he was kicked out of his home. After about a month, Jackson dropped out. He was $2,000 in debt, with no college credits to his name and nowhere to live.

In the 13 years since, he’s held jobs as a waiter, a singer with a Motown-style band, and a nursing assistant. He’s currently attending a free program at Per Scholas, which provides job training in technology. When he’s finished, he hopes to land a job that will allow him to help people and pay rent. For now, he calls a Bronx men’s shelter home.

Neither Greenberg nor Jackson is working in music. Both have been largely self-sufficient throughout their adult lives. But while Greenberg’s upbringing laid a foundation for his evolving dreams—one built on familial and community expectations, with an emphasis on education—Jackson had less to fall back on.

First-generation and lower-income students often have trouble navigating the opaque higher education system. In fact, poorer students who perform well on standardized tests generally don’t apply to selective colleges and universities, according to research by Stanford economist Caroline Hoxby, even when they’re highly qualified.

College admission is only part of the mobility story in the U.S. and around the world. Elite college graduates dominate Chile’s top corporate jobs, for example, but women and poor men who attend top schools aren’t among those with better access to the most elevated roles. The country’s preferential network goes beyond alma mater, suggests economist Seth Zimmerman at University of Chicago Booth School of Business, to favor men who went to pricey private schools.

Despite all the unwritten rules, invisible cultural barriers, and hard-to-breach social divisions, education and training can help to level an uneven playing field. It’s an imperfect relationship, but places with educational mobility—where parental education is less likely to determine a child’s education—also tend to have better income mobility, World Bank researchers find.

Terri Collins, 31, is hoping to break through her circumstances. She was raised by her mother, who worked on and off as a home health aide, but mostly they lived on her grandmother’s pension. Collins was a good student who wanted more than Brooklyn’s Flatbush neighborhood seemed to offer. “I wanted to get out,” she says. “You’re in control of your own destiny: That was always ingrained in me.” She got a scholarship to study English at Union College in upstate New York.

It was a promising start, but it wasn’t enough to secure her path to prosperity. Her grandmother died before she left for college, and her mother passed away while she was in school. At her 2011 graduation, Collins found herself alone, grieving, and with few prospects in a tough economy. “My opportunities were limited to whatever I could land a job in,” she says. She’s worked in sales ever since but has struggled with strict quotas and meager advancement opportunities.

Collins is now living in Harlem and studying at Per Scholas, where’s she’s completing a 15-week training program in IT Support. She goes to class five days a week, usually from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., then clocks a shift at a Trader Joe’s from 5 p.m. to midnight. Per Scholas has a good track record: About 85 percent of students at its Bronx location graduate, and 80 percent of them report getting jobs related to their training within the year. New York City’s tech industry, like the nation’s, is thirsty for qualified workers.

Participants in the philanthropy-funded program have to fall below 200 percent of the federal poverty level to qualify, and admission is selective—only 25 percent of applicants get in. But such approaches could help reduce America’s twin gaps: opportunity and skill. Collins hopes it’s a ticket to a fulfilling career. For now, she’s “ringing up zucchini and heads of lettuce and cabbage, and apologizing for being out of cauliflower gnocchi,” she says. But she’s keeping her dreams alive. “This is not permanent if you don’t want it to be.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.