A Long Legal War Over a $10 Billion Takeover Heads to a Close

A Long Legal War Over a $10 Billion Takeover Heads to a Close

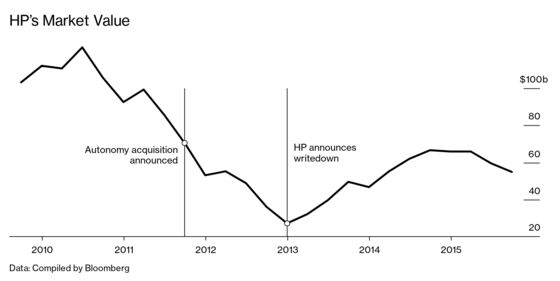

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Back when everyone still said “big data” instead of “machine learning,” the U.K.’s Autonomy Corp. considered itself an early leader in sorting and analyzing huge troves of information about online behavior, from video views to Facebook likes. Hewlett-Packard Co. thought so too and, in 2011, wrote a $10.3 billion check to buy it.

That was validation not only for Britain’s “Silicon Fen” but also for Mike Lynch, the University of Cambridge graduate with a Ph.D. in mathematical computing who founded Autonomy in 1996. After building it into the country’s second-biggest software company, he personally made $815 million from Autonomy’s sale. The adulation quickly turned to scandal, however, for both HP and Lynch.

In 2012, HP wrote down the vast majority of the deal and alleged that Lynch had orchestrated a massive accounting fraud to dress Autonomy up for a sale. The company says it wants $5 billion in damages from Lynch and Sushovan Hussain, Autonomy’s finance director. But the nine-month, £40 million ($51 million) U.K. civil trial—among the longest and most expensive in modern British history—has painted an unflattering picture of the American corporation, full of infighting and internal skulduggery, documented in dueling emails and testimony from top HP executives. When HP split in two in 2015, Hewlett Packard Enterprise Co. (HPE), the half that kept the AI division under former Chief Executive Officer and EBay Inc. legend Meg Whitman, continued the legal fight against Lynch.

Lynch, 54, is on the cusp of something approaching either redemption or defeat. A ruling is expected by midyear in HPE’s civil suit, and sometime in March, another British court will begin considering whether the U.K. should extradite him to California to face criminal fraud charges brought by the U.S. Department of Justice. A civil decision in his favor could make extradition less likely; defeat would make it more so. Spokespeople for HPE and Lynch declined to comment on the civil trial and extradition case, beyond representations each side has made in court.

Lynch and Hussain deny overseeing any fraud, arguing that HP simply ran their business into the ground and that it had rushed into its agreement to pay a 60% premium for Autonomy, which wasn’t desperate for a sale. Lynch says the $5 billion figure was entirely reverse-engineered, barely an estimate calculated on the back of an envelope, and manufactured to explain away HP’s disastrous management of the acquisition. He brought emails to court to show that the day HP alleged fraud, investors in his fledgling venture capital firm pulled their money out. Lynch lost a high-profile government advisory role, too. “The effect was like a bombshell,” he told the court.

The verdict hangs on whether High Court Justice Robert Hildyard believes Lynch and his subordinates deliberately inflated Autonomy’s value. HPE’s attorneys characterized Lynch as a controlling and dishonest CEO with intimate knowledge of his company’s accounting practices. They’re relying in part on an admission by Autonomy’s U.S. sales director, Christopher Egan, that Egan booked fraudulent transactions to inflate the company’s revenue, actions Lynch denied knowledge of.

Lynch is counting on Hildyard finding that HPE failed to produce a smoking gun for the fraud it alleges. At the moment, Lynch seems to have an advantage on his home turf. HPE pursued Lynch through a U.K. civil court after prosecutors at Britain’s Serious Fraud Office found “insufficient evidence” to proceed with their own criminal case against Lynch and Hussain. Robert Miles, Lynch’s attorney, has used internal company documents to argue the case was a function of infighting at HP, where top executives disagreed about the Autonomy purchase and the board wavered on strategy.

The Autonomy purchase was critical to former HP CEO Léo Apotheker’s plan to shift the PCs-and-printers company’s focus toward software. Apotheker, an outsider who came from Germany’s SAP AG, encountered internal opposition to the takeover, according to documents shown in court. Cathie Lesjak, the company’s then-chief financial officer, registered a surprise vote against the deal at a board meeting in August 2011, blindsiding Apotheker, he said in court. In the same meeting, she privately emailed Ray Lane, HP’s chairman at the time, to say, “We are reactive and act without good planning. There is no financial discipline.”

That afternoon, Lesjak sent a second, one-line email to Lane hinting at Apotheker’s sinking fortunes. “One PR person says ... Leo is a dead man walking ... he had never seen worse press for a CEO,” it read. Apotheker defended his deal in a Sept. 4, 2011, email to Lane—two weeks after it had been publicly announced, alongside a reduction to sales forecasts and a wider company strategy shift: “If Autonomy and more software isn’t the solution, what is the alternative?” he asked. Even Peter Weinberg, HP’s own mergers-and-acquisitions adviser, called the atmosphere inside HP “poisonous” in an email he wrote to Apotheker, the court heard. On Sept. 22, 2011, Apotheker was fired after 10 months on the job. Whitman, one of the company’s directors, replaced him and announced the writedown and fraud allegations in November 2012.

HPE argued that Lynch and Hussain conned HP into overpaying by presenting financial documents filled with phony transactions from supposed resellers. The software was simply “not as good as Dr. Lynch and no doubt everyone else hoped,” so Autonomy increasingly cooked its books to keep revenue on an upward trajectory until the whole company began to resemble a Ponzi scheme, HPE attorney Laurence Rabinowitz said.

This side of the story lost some credibility during testimony by Lesjak, the former HP CFO. How, the judge wanted to know, did she and her colleagues assess $5 billion in fraud? Lesjak said the math was done on a whiteboard and wiped clean. When pressed by the judge for any written record of the calculation, she said it was a verbal conversation and didn’t know if it had been put in writing. Lynch’s attorney shared an email showing HP’s executive team knew the figure was shaky. “We are getting a lot of push back from media that they cannot understand how the accounting issues at AU could result in a $5 billion writedown,” HP’s public-relations chief wrote to Lesjak and corporate controller Marc Levine in a Nov. 29, 2012, email entered into evidence. “We’ve never formally prepared anything to attribute the irregularities to the amount of the write down,” Levine replied.

In his closing argument, Rabinowitz said the company got the figure by calculating that Autonomy’s growth and margins would be lower. “Overstated” revenue was one of the factors in the drastically cut valuation, he said. Judge Hildyard’s final exchange with Rabinowitz, 93 days and 58 witnesses after the trial started, suggested this question might’ve proved a sticking point. “One often wonders when fraud is suggested, what can have been its purpose?” he asked. Autonomy was being readied for sale, Rabinowitz said. “OK, I shall look at that,” Hildyard responded before adjourning.

The decision is crucial for Lynch, because his prospects in the U.S. don’t seem great. He could face a prison term as long as 20 years if he’s extradited to the U.S. and found guilty in a criminal case there. In 2018 a San Francisco court convicted Hussain of fraud, and he was subsequently sentenced to five years in prison. Hussain has appealed. His lawyer in the U.S. case had argued that HPE deployed an army of company lawyers and consultants to support the government prosecution, which he said relied on false testimony from cooperating witnesses. Hussain’s lawyer for the U.K. civil trial leaned on Lynch to make the executives’ case in Britain, with Hussain opting to stay in the U.S. to focus on appealing the criminal ruling there. A representative for Hussain didn’t immediately return a Bloomberg request for comment.

An HPE victory would offer some vindication for shareholders with long memories. Autonomy, whose assets the company mostly sold off a couple of years back, was its biggest disaster, capping a run of lousy acquisitions before HP split. (Remember the Palm tablet? Neither does anyone else.)

HPE has cautioned against putting too much weight behind the U.K. civil court judgment. There’s no reason it would be “relevant or even admissible” in a San Francisco criminal court, the company said in its closing argument. Political allies of Lynch, on the other hand, argue that if he’s cleared in the civil case, he shouldn’t be extradited. David Davis, a member of Parliament, said in a January speech in the House of Commons that if HPE fails to win its civil case against Lynch, the case for extradition “would evaporate.” Lynch has become part of Davis’s broader crusade against what he calls a one-sided U.S. extradition policy. Most recently, the U.S. Department of State refused to extradite an American intelligence official’s wife to the U.K. on charges that she killed a teenager while driving on the wrong side of the road outside a military base in England.

Lynch’s lawyers have another strategy to keep him out of the San Francisco courtroom: arguing that a person shouldn’t be extradited if the alleged offenses could have been tried in the U.K. This has worked twice recently, with a British trader and a computer activist.

If Lynch can keep himself on British soil, he’ll be able to refocus on wooing investors for his venture firm, Invoke Capital. Invoke is important to Lynch’s standing, and that of the U.K. tech community, in more ways than one. Darktrace Ltd., a prominent U.K. cybersecurity startup that Invoke has backed, is considering going public. Something that could help Lynch’s ventures: The $160 million he’s sought, in a countersuit, from HPE to account for alleged damages to his reputation.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rebecca Penty at rpenty@bloomberg.net, Jeff Muskus

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.