How to Persuade White Lawmakers to Protect Black Hairstyles

How to Persuade White Lawmakers to Protect Black Hairstyles

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Four years ago, when Faith Fennidy was 10, her mother called her down to the living room to watch something that seemed crazy. On TV was a report about Deanna and Mya Cook, 15-year-old twin sisters in Massachusetts whose school had given them detention, threatened them with suspension, and banned them from track meets, Latin club, and the prom—all for braiding their hair. The twins were wearing the simple box braids ubiquitous among generations of Black women and girls, Fennidy included. Often done using extensions, they’re a staple Black hairstyle, because they help protect hair from damage as it grows and are relatively easy to maintain. The sisters’ charter school said it had punished the girls because its policies on student hair and makeup forbid extensions.

Faith recalls watching the news report in a daze, shocked that hair like hers could lead to such punishment. At the time, the story made the Cooks’ charter school in Malden, Mass., sound very far away from her Catholic elementary school in Terrytown, La. “I don’t think I would have ever believed that it would have happened to me,” she says.

But a year later, it did. Faith’s school amended its dress code to ban hair extensions in similarly neutral-sounding terms, and soon she was sent home for the day for violating the policy. A clip of her leaving school in tears went viral, and a still from the video appeared in the New York Times. “I was just so upset in that moment,” she recalls. She transferred schools.

Faith, like the Cooks, had joined a fresh wave of Black students and workers over the past several years who were being rejected, punished, or fired for wearing traditionally Black hairstyles, such as cornrows and locs, also known as dreadlocks. Dress codes have been used to justify blocking students from their first day of kindergarten and from walking in their high school graduation ceremony. In Des Moines, a trucking company dismissed a recent hire who wouldn’t cut his locs during training, claiming they posed a safety issue. But more often, employers say they just don’t like the look. In White Plains, N.Y., a Banana Republic manager refused to schedule shifts for an employee until she removed her box braids, which he deemed unkempt. In Arlington, teens who refused to cut their braids and locs were denied jobs at Six Flags Over Texas, where until 2017 the namesake banners included the flag of the Confederacy.

In some of these cases, the amplifying effect of social media has shamed employers or schools into reversing the decisions. Following national backlashes, Faith’s former school, Christ the King Parish School, eventually rescinded its hair policy. So did Mystic Valley Regional Charter School, where the Cooks went. Banana Republic fired the offending manager and said it has zero tolerance for discrimination. On the other hand, Six Flags didn’t hire the long-haired teens (it tries to accommodate workers on a case-by-case basis), and the Des Moines trucking company, TMC Transportation, maintained that its trainee’s locs violated its safety policies by rendering him unable to wear a hard hat properly, a claim the trainee denied. Throughout the U.S., these kinds of issues continue to pop up, whack-a-mole style, showing how Black Americans regularly face discrimination that violates the spirit, if not the letter, of the laws protecting their rights in the workplace.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits explicit discrimination by employers and public schools on the basis of traits the law considers immutable—unchangeable from birth—such as race and color. But the language doesn’t explicitly ban discrimination against mutable traits, leaving many common, implicit forms of discrimination to be adjudicated by the courts. For decades, workplaces have argued, mostly successfully, that hairstyles predominantly worn by Black people are merely cultural practices and should be subject to change by employers or school administrators. The federal judiciary has so far protected only the afro, which was deemed an immutable racial characteristic in 1976. This discrepancy is absurd at best: Not all Black people have afros, and people who aren’t Black can have natural afros, or brown skin, for that matter.

Lawmakers and judges have a ways to go to catch up to the reality that race is a social construct, says Wendy Greene, a law professor at Drexel University who’s advised efforts to outlaw discrimination against natural hair. “There’s a very limited understanding of what constitutes race and therefore a very, very constrained and limited understanding of what constitutes unlawful race discrimination,” she says. “I call this legal fiction.”

This limited understanding extends to the nuances of Black hair, from its rich history and culture to its morphological differences. Simply combing my hair requires water, a palmful of deep conditioner, a flexi-bristle brush, and a ton of time and patience to tease through each tightly coiled strand. When I was a girl, my mother spent two hours or more every other week washing, blow-drying, and styling my afro, carefully detangling, sectioning, twisting, plaiting, and securing the hair. But even her most meticulous dos were no match for the guaranteed frizzfests that resulted from dance classes, pool parties, or sleepaway camp. And as a single mother, she only had so much time to style me and my two sisters. Altering my hair texture wasn’t an option; Mom distrusted the chemicals used to permanently straighten hair and the heat tools that could temporarily do the same. So like Faith, the Cook sisters, and so many sistas before and since, I turned to box braids, Senegalese twists, cornrows, and other protective styles that, like locs, last for weeks or longer, endure water, and generally look pretty damn good.

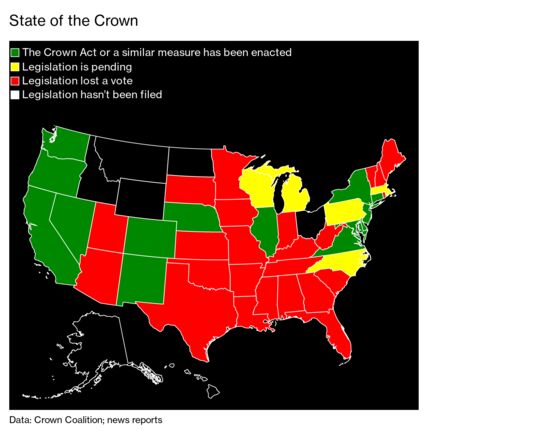

For me and others who’ve had similar experiences, it’s self-evident that these styles are so historically and culturally tied to Black people that they constitute immutable characteristics protected under the Civil Rights Act. Since 2019, a growing network of government officials, activists, and legal experts have been arguing as much across the country, fighting state by state to eliminate hair discrimination. Within that movement, the Crown Coalition group of more than 80 advocacy and nongovernmental organizations has taken the lead. Its primary tool is a template bill called the Create a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair Act, or Crown Act. A version of the bill has stalled in the U.S. Senate, but the basic framework is now law in 14 states and has been introduced in the legislatures of dozens of others.

In some states (California, Connecticut, New Mexico), the campaign to persuade lawmakers to pass it into state law has received a resounding yes. In others it’s been more of a grind, as Black people and advocacy groups and their allies lobby a vast sea of melanin-challenged public officials to take action on a problem that doesn’t personally hurt or disadvantage them. And wouldn’t you know it: Black people have had a little bit of experience in that area.

Natural hair discrimination in what’s now the U.S. dates to the early 1600s and the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Along with physical violence, slavers used psychological and emotional abuse to instill a sense of inhumanity and inferiority among their victims and to help justify treating them as property. These tactics included pathologizing physical traits that contrasted African enslaved people with European slavers, including tightly coiled hair textures, which were often ridiculed as “woolly.” The prejudice outlasted Britain’s control of its American colonies, the U.S. Civil War, and abolition, too.

Through Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era and deep into the 20th century, Black people used hair to exercise a measure of control over their individual and collective identities. Those efforts, however, often involved adopting stylistic trends that emulated European beauty standards and glamorized straight hair. During the 1970s the Black Power movement spurred support for natural hair. And a landmark 1988 decision by the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission helped catapult the issue’s political significance onto the national stage. In the climax to a string of hair discrimination cases involving working Black women, the EEOC ruled that Hyatt Hotels violated the Civil Rights Act when it specifically banned braids and cornrows and fired two Black women for violating that policy.

The EEOC decision has been cited in federal and state discrimination claims and lawsuits as evidence that federal laws protect Black hairstyles, but the case didn’t set a binding precedent. For decades afterward, few national media figures or advocates connected the dots between cases of hair discrimination or pushed to keep them in the news, so individual incidents could be dismissed as isolated or apocryphal. That’s changed, however, in the era of social media. “Now, within hours of something happening, we can all hear about it and maybe even see video,” says Ayana Byrd, a co-author of Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America.

The 2010s ushered in a modern-day natural hair movement. It started on the coasts and on college campuses, then expanded via online communities. Aptly, the coalition behind the Crown Act began to take shape in New Orleans at the 2018 Essence Festival, America’s biggest annual celebration of all things Black Girl Magic.

At the festival, Adjoa Asamoah, a consultant for political campaigns (including, last year, Joe Biden’s) and corporate brands (Anheuser-Busch), met Esi Eggleston Bracey, chief operating officer of Unilever North America’s beauty division, and Kelli Richardson Lawson and Orlena Nwokah Blanchard, who run a Washington, D.C., marketing firm called Joy Collective. Hair discrimination had been on each woman’s mind, and they saw in one another’s strengths a path for reform. That year, the group officially formed the Crown Coalition and began recruiting allies.

“There was no one incident of discrimination that prompted the work,” says Asamoah, who developed the legislative strategy. It was an overdue answer to “this prevalent form of racial discrimination.” She partnered with state Senator Tremaine Wright in New York and state Senator Holly Mitchell in California, whose signature look is blond locs. A year after the meeting in New Orleans, both states passed versions of the Crown Act, and Unilever’s Dove brand joined the Crown Coalition, providing financial support and amplifying its message.

With Dove funding, the Joy Collective conducted a study of 2,067 women that found Black women were 80% more likely than others to change their natural hair to meet social norms or expectations at work, 30% more likely to be made aware of a formal workplace appearance policy, 150% more likely to be sent home or know of a Black woman sent home from work because of their hair, and 83% more likely to report being judged more harshly on looks than other women. The study also found that Black women’s hair was roughly 3.4 times more likely than others’ to be perceived as unprofessional. Respondents ranked locs, braids, bantu knots (a style resembling stacked spiral knots), and other natural Black hairstyles the least professional.

During the first phase of Crown Coalition lobbying, this sort of data proved galvanizing in some blue states, seven more of which quickly passed the bill. The bar was higher in Nebraska, where Republican Governor Pete Ricketts vetoed legislation inspired by the Crown Act in August 2020, shortly before it was set to become law. In a statement announcing his decision, Ricketts said he agreed with the bill’s aim to prevent discrimination based on immutable characteristics. But hairstyles, he said, didn’t meet that standard, and employers needed flexibility to adhere to health and safety regulations. “While hair type is an immutable characteristic, hairstyles can easily be changed,” he wrote, adding that the hairstyles referenced in the bill, such as twists, cornrows, and locs, are not attributable to or exclusively worn by one racial group. He promised to work with the state legislature to resolve his concerns.

This was the first veto of such a bill. Ashlei Spivey, a lobbyist who founded the Omaha-based advocacy group I Be Black Girl, heard the news while celebrating her 34th birthday. “Being a Black woman, doing this work on behalf of Black women, femmes, and girls, I took it personal,” she says. She, her colleagues, and Greene, the law professor, helped prepare a new version for introduction by state Senator Terrell McKinney early this year. Together, they resolved to address the governor’s concerns without excising specific hairstyles from the revised bill. It turned out to be something of a tug of war.

McKinney began negotiations by proposing language much the same as the original bill, without much in the way of compromise. Ricketts countered with language that the state senator says would have removed the bill’s teeth. McKinney says that even when agreement seemed impossible, he and the Crown Act’s other advocates remained cordial and “didn’t throw any shots.” Instead, they kept communications with the governor’s office going and made behind-the-scenes appeals to leading legislators and health officials. This August, a year after the first veto, they had a deal, and Ricketts’s signature. (The governor’s office didn’t respond to a voicemail seeking comment.) Spivey says her 35th birthday was better.

Nebraska’s Crown Act allows law enforcement agencies to set grooming standards—a significant concession, but much better than a fresh veto, McKinney says. Among other things, it’s a counterpoint to the gridlock strangling most of the legislative proposals that await votes in Congress. As McKinney watched Ricketts sign the bill into law, his first enacted as a freshman senator, he says, he thought, “I’m here. And I can actually get something done.”

The latest round of Crown Act advances has been more stutterstep than Nebraska’s. In Washington, a national bill passed the House of Representatives last year, but the legislative session ended in December without a corresponding vote in the Senate. That means both chambers must pass a new version introduced earlier this year by a handful of leading House members and Democratic Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey. So far, there’s been little progress. Federal response to a once-in-a-century pandemic obviously takes priority, though the Senate did make time last year to pass more than 60 bills renaming U.S. Postal Service facilities.

A version of the bill is already law in Booker’s home state and in Maryland, where Mya Cook is now majoring in psychology at the University of Maryland. She says her latent interest in the subject spiked after she and her sister were threatened with suspension in Massachusetts over their box braids. Part of her motivation in choosing her major, she says, was to try to puzzle out the whys of what happened to her in high school. “Just so I could even understand, because it never made any sense,” she says. She pauses. “I don’t even think even now it would make sense, honestly.”

In Massachusetts, getting a vote on the Crown Act has been slow going. State Representative Steven Ultrino, who counts the Cook family among his constituents, says that their 2017 case marked the first time he’d received a complaint about hair discrimination and that he had a lot of learning to do. Staff research and consultation with Crown Coalition leaders helped yield the bill he introduced last year. He held hearings, lobbied colleagues for support, and got the bill passed in the Massachusetts House. He says he’s since received a flood of calls from workers and parents who’ve had to deal with hair discrimination.

Key to Crown Act outreach efforts in Massachusetts, Ultrino says, has been relaying to other legislators the horror stories he’s heard from constituents, getting those constituents involved, and asking his Black colleagues to share their experiences, too. He tends to describe his advocacy on this issue in terms familiar to people with chronic health conditions in their families—which is to say, everyone. “I support Alzheimer’s research,” he says. “I don’t have Alzheimer’s.” As was the case in Washington, Covid helped push the bill off the Massachusetts upper chamber’s 2020 docket, but the 2021 version is working its way through the state House’s judiciary committee, and it stands a good chance of becoming law as soon as it can get full floor votes.

Already, more than 121 million Americans are now protected by Crown Act legislation or something like it. On the Crown Coalition’s website, a map of the state-level efforts calls the group’s shot with the headline “14 down, 36 to go.” Asamoah declined to comment on the next phase of the group’s strategy, beyond saying it varies significantly by state.

The odds have seemed tough in redder areas, but earlier this year, Louisiana came close to being the second Southern state, after Virginia, to ban discrimination against natural hair. None of the three bills lawmakers proposed quite got the needed votes before the legislative session ended in June, however. A version introduced by state Representative Candace Newell came closest, with 46 votes in favor and 48 against.

Republicans accounted for nearly all the nays, arguing that Louisiana should let local school districts make their own rules as much as possible. Newell notes that many of these legislators haven’t applied this line of reasoning to their efforts to ban public schools from mandating masks or teaching critical race theory. She attributes her bill’s defeat partly to intensifying partisan tension and says she’ll try again in the next session. “It’s going to be a heavy lift,” she predicts. Her blond, natural-textured hair is part of her effort to educate people on the issue. “I just try to bring it to my colleagues,” she says, that her hairstyle “doesn’t affect my capability of trying to bring this state to a better place.”

Ahead of the next fight, Newell plans to work with a lobbyist, seek support from the Louisiana Association of Business & Industry, and explore ways to assuage the concerns of moderate Republicans who might be swayed into the yea column. She’s also had to learn to translate her arguments for those colleagues who just don’t spend much time around locs or cornrows. “I think the most interaction most of them have with Black people is when they come up to the capital session,” she says. “It’s not a good thing. It’s not a bad thing. It’s just their reality.”

More disquieting to her is the degree to which even some of those writing the laws assume that everyone enjoys the same legal protection they do as White people, rather than recognizing it as White privilege. During one hearing on a different bill seeking to outlaw hair discrimination, a White female colleague was asked how she would feel if she were fired for refusing to get a perm.

“She said, ‘Well, that wouldn’t happen, because I have the Constitution to protect me,’ ” Newell recalls. “That just ran through me.”

Now 14 years old, Faith Fennidy has a mouthful of braces, a house full of pets, and her own strategies for defending Black hair. Outside her home in Harvey, La., Faith’s braces glint in the hot sun as she introduces me to her ducks, Draco and Daisy. In the shaded section of her manicured backyard, I meet her dog Mimi, a rambunctious Yorkie. Her bright yellow bird, Lululemon, hops around a large cage on the coffee table before us.

When she’s not caring for her pets or playing volleyball, Faith is devouring the books taught in her English class, analyzing the characters’ motives and contemplating figures of speech. A good story can go a long way toward building empathy, she says, citing To Kill a Mockingbird as an example. The character she most relates to isn’t the protagonist, Scout Finch, or Atticus, Scout’s fiery lawyer dad. It’s Scout’s brother, Jem. The boy loses his innocence when he realizes that what happened to their neighbor Tom Robinson, a Black man who meets a brutal end after being falsely accused of a crime, is going to keep happening to more Black men.

“When I saw my video went viral, I thought it wasn’t going to happen anymore,” Faith says of punishments like hers and the Cooks’. But after seeing story after story of other Black people experiencing the same pain, “I really just felt it was going to keep continuing until there was a way to stop it.”

Read next: Diversity Doesn’t Just Happen Naturally, and Directors Are Finally Realizing It

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.