The Rise of the Professional Dungeon Master

The Rise of the Professional Dungeon Master

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On a recent Friday evening, Devon Chulick stood in the kitchen of his San Francisco apartment brewing potions. A dry-erase game board with a grid of black squares to assist in drawing maps was laid neatly across the coffee table in the living room, along with a dozen or so miniature elves, wizards, and drow rogues, which had been released from their Tupperware prisons.

In an hour, a trio of twenty- and thirtysomething Google employees were scheduled to arrive for an entry-level Dungeons & Dragons game. “They’ll love this,” Chulick said, sloshing the brew, a combination of water, vanilla, and cherry bitters; while not exactly essential to the quest, the concoction “adds to the experience.” Tall, bearded, dressed in black up to his glasses, Chulick looked the part of a Silicon Valley product manager—which he is, at bro-tastic swimwear company Chubbies. But in his free time, he said, “everything is fantasy.”

Since October, he’s been moonlighting as a dungeon master-for-hire, catering primarily to those entering the world of D&D for the first time and seeking instruction in the game’s owlbears, Icewind Dale, and other mythological features, plus a few clients who are dusting off the rule books they put away with other childish things in the early 1980s. Until a few years ago, the idea of engaging a professional dungeon master, or DM, would have seemed absurd. In the old days, if a DM accepted payment at all for the work of organizing and creating challenges for a game, it was usually in pizza slices or beer, depending on the age group involved. Most of the time, your DM was a buddy with a talent for making up stories. Demand, paid or unpaid, was relatively anemic.

But D&D has gained more mainstream followers of late, thanks especially to the Netflix show Stranger Things, which premiered its third season on July 4, but also to the racy teen soap Riverdale and the behemoth fantasy book and television series Game of Thrones. (D.B. Weiss, one of GoT’s creators, says he’s played D&D “compulsively for years.”) In consequence, professional dungeon mastering has become a business—and for some, even a career.

You can hire Chulick, for example, to lead an individual beginner campaign, which will set you back $300 and last up to four hours; for $500, he’ll come to your office and run a D&D team-building activity. He rents a full studio set up to stream the games he runs weekly on the gaming platform Twitch, where he has 150 subscribers who each pay $4.99 a month. He also has an email list of 4,200 people and four sponsors who provide detailed custom game pieces, beer, or maps in exchange for on-air endorsements. For a negotiated fee, he’ll draw up custom battle maps, consult on purchases of various game accessories, and host bachelor parties, family gatherings, or kids’ birthdays. At present, he’s booked out several months and has a waitlist.

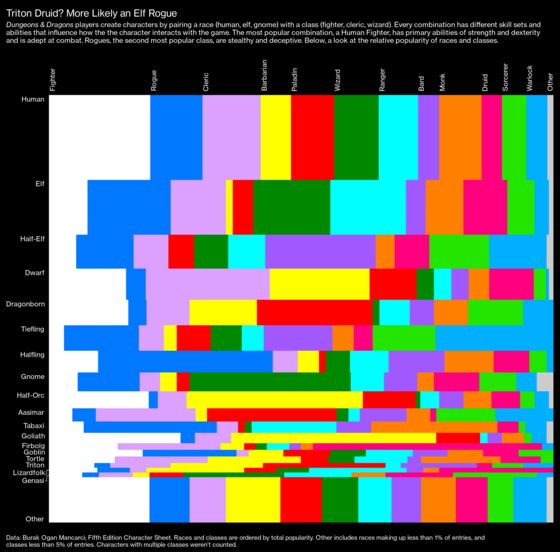

D&D players adopt predetermined fantasy personae and embark on a mission of the DM’s design. Participants push the plot ahead by rolling a 20-sided die to cast enchantments, slay monsters, etc.—thus, no two games are alike. A campaign can last a couple of hours or all night; some play out over months, depending on the DM’s story. Think of it as a superhero movie franchise: You can watch the first installment and stop at the cliffhanger, or keep going through all the sequels.

Being a professional DM is, in many ways, the perfect side hustle. The latest edition of D&D gives them a fair amount of freedom to stretch creative muscles in designing a quest, and the better storyteller a DM is, the better the overall experience for the players. “I think there’s a therapeutic part to it,” Chulick said. “Escapism is great. This is easy to access, a bit more immersive.”

“It’s a new trend, and we’re aware of it,” says Nathan Stewart, vice president of the Dungeons & Dragons franchise at Wizards of the Coast, which has published the game since it acquired the original publisher, TSR Inc., in 1997. “The idea that people are making a living being a professional dungeon master is cool and mind-blowing.”

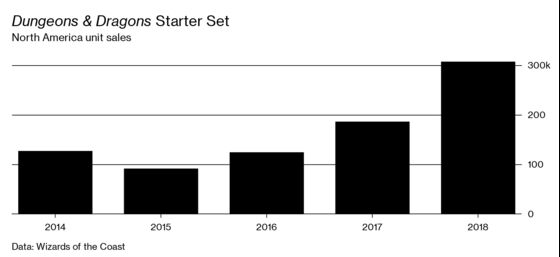

Wizards has been a subsidiary of Hasbro Inc. since 1999. Stewart says sales of the fifth edition of the game, which was first published in 2014, were up 41 percent in 2017 from the year before, and soared another 52 percent in 2018, the game’s biggest sales year yet. According to Wizards, an estimated 40 million people play the game annually. While Dungeons & Dragons hasn’t dominated the e-sports world like, say Overwatch, D&D streams are a growing market—and a way to hook new gamers. In 2017, 9 million people watched others play D&D on Twitch, immersing themselves in the world of the game without ever having to pick up a die or cast a spell.

While most of the game’s impassioned fans seem to be thrilled with its suddenly wide appeal, a handful of purists bristle in online forums that professional dungeon mastering creates a tangle of ethical quandaries. “There are different kinds of people who play D&D, and some can be very difficult to deal with if they’re not your friends,” says Sven Andersson, a DM in Gothenburg, Sweden, who has run games since his adolescence in the 1980s, all unpaid. The game is inherently cooperative, but unruly players have been known to try to dominate or even sabotage campaigns. It can be part of the DM’s responsibility to bring them to heel. “What do you do if you have a player who is a bully or a player that is doing something distasteful in the game?” Andersson asks. “And he’s your client? Do you just boot him from the game? I don’t know.”

Wizards of the Coast’s Stewart, DMs, critics, and players credit the greater accessibility of D&D’s fifth edition, which streamlined the game’s notoriously epic rulebook and eased some technical requirements, with helping usher in a new generation of enthusiasts. But forces outside of Wizards’ control have played an undeniable role. “Geek culture as a whole is off the charts,” Stewart says.

Like many of his colleagues, Stewart played D&D in his youth. He joined Wizards in 2011 by way of a career in brand marketing at companies including Namco, Electronic Arts, and the Xbox division of Microsoft. As head of D&D, he leads the development of the franchise in analog and digital forms. “You no longer have to explain what magic or a dwarf or a dragon is, and no one is snarky when you bring it up,” he says. “They can see on Twitch that it’s people sitting around, making each other laugh and telling stories. And you think, I could do that.”

To meet the rising D&D demand, some professional DMs now train other professionals. Rory Philstrom, a pastor with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, based in Bloomington, Minn., is also a self-described “semi-professional” DM. His website features a photoshopped image of Jesus holding a D-20 die and reads: “As baptized children of God, we can do all things through Christ who strengthens us. One of those things happens to be: play Dungeons & Dragons like a boss.” He hosts a four-day retreat, Pastors and Dragons ($440 to $675, depending on your lodging preference), at which you’ll learn how to use D&D as a tool to explore Christian teachings and enhance the work of your ministry. He’s also run an eight-session campaign for his confirmation class, and his church hosts a game night twice a month. “It’s been a blast,” he says.

Philstrom partially credits the game with helping him build collegial relationships and navigate the “realities of ministry” since his ordination in 2012. “When you’re at the table, people are putting themselves out there. They take the contents of their imaginations and translate it into story. You can ask people what they want to be, and people show all sorts of facets of their personalities,” he says. His fantastical style is particularly gutsy considering that Dungeons & Dragons was once the focus of a moral panic among far-right Christian groups. The 1980s, in particular, saw scores of accusations that the game endorsed witchcraft and satanic worship. Opponents tied it to murders and suicides, claims that have long since been debunked.

The growing popularity of the game online has created more new kinds of opportunities, including for those who’ve struggled to build more traditional careers. Bethany Dillingham, a professional DM in Goldsboro, N.C., says her childhood love of the game went on a hiatus when she entered the U.S. Navy as a man in 2008. She left seven years later and started her gender transition. “It made me unemployable,” she says. “I looked online for ways to connect with people.”

She began to offer her services as a paid DM online. “I saw that the ratio of players to dungeon masters is dramatic,” she says. “People want to play badly enough. I said, ‘Let’s do it and see if it works.’ Oddly it has.” Dillingham runs eight games a week, each one running about four hours and costing $15 a player. Her typical workday starts with game prep a couple hours ahead of her first campaign with European or Australian fans, usually around 10 a.m., and lasts well into the evening with American players. “I have no real days off,” she says. She’s begun to parlay her D&D skills into work as a production and talent manager for “a group of theater nerds” who want to build theatrical experiences around D&D and other role-playing games.

At the higher end of the professional price spectrum is John Clark of Los Angeles, a studio department head for Paramount by day and DM to the stars by night. Clark’s business grew out of moderating the Los Angeles D&D MeetUp group, one of the largest such groups in the country with 950 members by the time he resigned a few years ago after the birth of his daughter. (It’s since grown to 1,700 members.) Noticing a demand for a higher level of DMing—more personalized, immersive, with a greater variety of performance techniques and more detailed plot development—he realized that his professional acting skills from his pre-executive career could be an asset. “You can’t just work for Cheetos anymore,” he says. “You have to have more value than that. If you don’t have the ability to do 10 different accents, be the life of the party. … I’m going to show up with the fun factor, and it needs to be super, super high.”

In addition to catering to his celebrity clientele (he politely declines to name names), Clark offers hourlong private lessons at $100 a pop. For an additional charge, he hosts campaigns in the Houdini room at the Magic Castle, the storied private club in Hollywood Heights.

In San Francisco, Chulick’s campaign was underway. Amanda Perry, Justin Stuart Paul, and Shashir Reddy sit cross-legged around a coffee table, sipping beers and snacking on vegetable pizza. Like most of Chulick’s clients, they had heard about his services by word of mouth. Perry said she dabbled in the game in junior high school and told a friend while rock climbing that she wanted to get into it more. (That friend, Bay Area-based handyman Robby Justesen, is one of the regulars in Chulick’s weekly Twitch stream. His character, Bruz, is a Level 8 barbarian, meaning he’s overcome certain challenges and thus unlocked more features.)

Chulick, perching on the edge of the couch, leaned forward to instruct the group in the night’s campaign. They were part of an “adventure company,” he said, “like Blackwater, but good.” After perusing the character sheets, they opted for an elf wizard, revered for its cunning with spells; an elf ranger, known for climbing prowess and wisdom; and a drow rogue, which can see well in the dark. “Can I call myself Orlando Bloom?” asked the elf ranger, aka Paul, referring to the actor who played the elf prince Legolas in the Lord of the Rings movies. Chulick said yes.

He reached over to his laptop and began to play mystical music complete with ocarina and pan flute, streamed from Spotify, as he set the scene for their quest: They were at a tavern, trying make their way through a forest. He took on the character of a Scottish-sounding bartender, imitated the growl of a beast in the woods, and squealed as a hag. The music shifted from epic soundtracks to ambient forest noises, spliced with the sounds of San Francisco’s Lower Haight through an open window. “Is that a real crow outside?” Perry asked at one point. “Or is that in the game?”

Brows furrowed as debates ensued over tactics. The three kept dutiful score on small dry-erase boards and carefully consulted their character sheets to determine what powers were available to them. “Remember,” Chulick said. “These are your teammates. You’re trying to succeed with them.” At one point, Reddy sold a life-insurance policy to a creature in the woods. In the end, after many dice rolls and decisions, the group slew the hag, and Chulick left them with a cliffhanger about who could be lurking in the woods ahead with a wand and an ultimatum.

“And that’s where we end tonight’s session,” he said, to a chorus of “ooooohs!” The players applauded, and Chulick fielded questions about the behind-the-scenes machinations of the puzzles and quests he’d guided them through. As they thanked him for his leadership and made their way to the door, Perry let out a sigh. “That was intense,” she said.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.