The Lasting Toll of a Deadly Virus

The Lasting Toll of a Deadly Virus

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For businesspeople around the world, the new coronavirus that sprang from China is producing a severe case of cognitive dissonance. Their eyes are telling them things are bad: rising fatalities, history’s biggest quarantine, sealed international borders, broken supply chains, shuttered businesses. But economists are telling them the epidemic will lower China’s 2020 economic growth by just a couple tenths of a percentage point and global growth essentially not at all.

So, which is it, a global crisis or a tempest in a Wuhan teapot? A lot hangs on the answer.

The oddly calm economic forecasts are based on the assumption that the draconian measures imposed around the world to isolate the sick and the potentially exposed will succeed in killing off the outbreak, at which point there will be a sharp economic recovery. That’s what happened after the 2002-03 outbreak of a closely related coronavirus that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

The base case of the professional economists at Bloomberg Economics is that China’s gross domestic product will expand 5.7% in 2020, vs. a pre-epidemic forecast of 5.9%. In their “prolonged outbreak” scenario, with containment not occurring until the second quarter, the economy grows just a tad less—5.6%. “Outside China and a few close neighbors, the impact would be difficult to see in the full-year growth data,” the economists wrote on Jan. 31.

This quick-bounce-back scenario may well turn out to be correct. While the number of new infections continues to rise, the daily rate of increase in China seems to have shrunk a bit if the numbers can be trusted. “There’s some reason for optimism, but it’s not conclusive at this stage,” said Michael Gapen, head of U.S. economics research for Barclays Investment Bank, on Feb. 3. “This week and next week are probably the most crucial.”

There are a lot of ways things could sour. The virus might spread more than expected, flaring up in countries that are less capable or less willing than China to impose a stringent cordon sanitaire. Businesses built to survive brief disruptions will go bankrupt if the epidemic drags on. And in the long run, even after this epidemic ends, it could leave scars, particularly in China itself. Corporate executives will be less keen to do business with the world’s workshop if it’s also perceived as the world’s incubator of deadly viruses.

Right now no one can be sure which way the story will go, as forecasters are the first to admit. “Rapid containment and escalating contagion are both possibilities, and would result in widely different growth forecasts,” the Bloomberg Economics forecasters, Chang Shu, Jamie Rush, and Tom Orlik, wrote in their Jan. 31 report.

What’s clear is that the viral epidemic is already hurting business. On Feb. 4, Hyundai Motor Co. said it was suspending production lines at its car factories in South Korea because of a shortage of parts made in China. Levi Strauss & Co. has had to shut a big store in Wuhan that opened just four months ago. Apple Inc., which earns about a quarter of its operating income in China, said on Feb. 1 it was temporarily closing all of its offices and stores there out of an “abundance of caution.” Airlines have cut flights in and out of the country. With transportation demand drying up, the price of Brent crude oil plummeted to $55 a barrel on Feb. 4, from $69 on Jan. 6.

Even news about the virus that looks positive is less so on second thought. Consider that, as of Feb. 5, the Philippines had reported only three cases of the virus, Cambodia one, and Indonesia zero. Given the close ties all three countries have to China and their lack of sophisticated surveillance technology and procedures, it’s likely that cases are simply being missed. What’s more, some leaders in the developing world seem dangerously blasé. Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen said at a press conference on Jan. 30 that people shouldn’t wear face masks because they create a climate of fear.

It’s conceivable that the disease could eventually become more of a problem outside China than inside it. In Africa, “it is very possible that we have cases that are going on on the continent that have not been recognized. We have to admit that,” John Nkengasong, director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, told reporters on Jan. 28.

The U.S. is better situated than Africa, but still vulnerable. Although President Trump bragged to Fox News in a pre-Super Bowl interview that “we’ve pretty much shut it down,” his administration has gotten rid of much of the apparatus for fighting epidemics like this one. The Washington Post reported in May 2018 that the top White House official on pandemics, Rear Admiral Timothy Ziemer, had left the administration and was not being replaced, and the global health security team he oversaw had been disbanded.

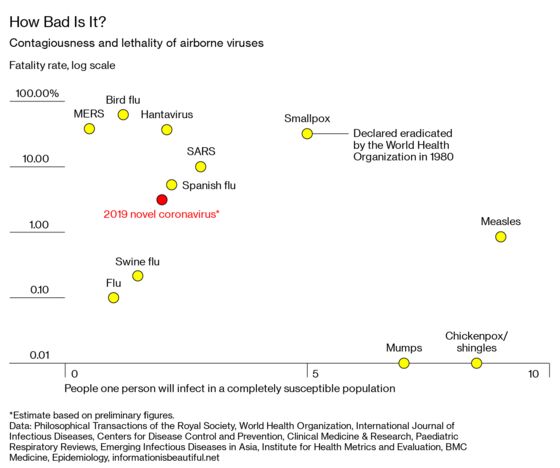

Evidence is mounting that the new virus is less lethal than the one that caused SARS, but possibly more contagious. People can pass it along when they have only mild symptoms or, in some cases, no symptoms at all. SARS wasn’t like that. So even though technically SARS is more transmissible in a wholly susceptible population—with a higher “basic reproduction number”—the new virus is more contagious under real-world conditions. Its lack of lethality will hold down the death toll, but the contagiousness will require continued isolation, quarantines, and social distancing.

At least that’s the current thinking. Success in fighting the virus depends not only on what people do, but also on the characteristics of the virus itself, which are still not fully understood. “It’s all about the bug,” says Dr. Mark Denison, director of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. “We’re along for the ride and responding as best we can.”

The number of people a virus will kill can’t be predicted solely from its basic reproduction number and its lethality—i.e., the percentage of people who die after becoming infected. The Spanish flu, which killed about 50 million people after World War I, was neither exceptionally contagious nor unusually lethal. It “happened to arrive in a setting when it could establish infections in a lot of people, in all parts of the world,” C. Brandon Ogbunu, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Brown University, wrote in an email. “And so, a 1-2% mortality rate ends up being a lot of people.” Spanish flu is the nightmare scenario for an unconstrained spread of a virus through vulnerable populations.

How to fight the new virus is a contentious issue that will become even more contentious if the measures adopted to date prove insufficient. The ethical question is the extent to which one group’s civil liberties can be abridged for the sake of the greater good. In medicine, there’s “a fundamental moral axiom that individual persons are valued as ends in themselves and should never be used merely as means to another’s ends,” says a 2007 essay by Dr. Martin Cetron of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Dr. Julius Landwirth of the Yale School of Medicine. “Public health, on the other hand, emphasizes collective action for the good of the community.”

China’s measures are imposing a real cost, both human and economic. In Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province, test kits and medical supplies are scarce. The sense of being trapped in a zone of infection is feeding understandable resentment. That could eventually boil over. In the Ebola outbreak of 2014, residents of the West Point neighborhood of Monrovia, Liberia’s capital city, rioted after they were put under a surprise quarantine.

President Xi Jinping is betting that tough containment measures now, unpopular as they may be in places, will pay off by extinguishing the virus and allowing normal economic activity to resume. He’s clearly unhappy that other countries are cutting their ties with China, which will delay the economy’s recovery. The Trump administration on Jan. 31 said foreign nationals who’d been in China in the last two weeks will “generally” be denied entry into the U.S. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs accused the White House of spreading fear and said other countries should not “take advantage of people’s precarious position.”

Trump’s restrictions on travelers from China are considerably more popular in the U.S., which so far has managed to keep a handful of imported cases of the virus from flaring up into outbreaks. American authorities hope the country can stymie the virus completely, or at least stall its spread until a vaccine is available.

One Trump administration official spotted a silver lining in the outbreak. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross told Fox Business network on Jan. 30 that he thinks it will help to “accelerate the return of jobs” to the U.S. and Mexico. (He added that “every American’s heart has to go out to the victims.”)

Ross’s timing may have been poor, and he ignored the harm that the coronavirus is doing to U.S. companies that sell to, buy from, or produce in China. But he’s probably correct that the fear of pandemics will shorten supply chains, encouraging companies and countries to produce more close to home. The coronavirus may further fray the bonds between the U.S. and China that have been stretched by Trump’s trade war and the mounting military rivalry between the two nations.

That, more than any fleeting effect on quarterly GDP, may be the longest-lasting business impact of the virus known provisionally as 2019-nCoV.

Read more: We’re Not Ready for the Next Global Virus Outbreak

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Eric Gelman at egelman3@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.