Big Tech Tries to Help the U.S. Narrow the Virus Testing Gap

Big Tech Tries to Help the U.S. Narrow the Virus Testing Gap

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When President Donald Trump finally addressed the nation’s dire shortage of testing capabilities for the coronavirus on March 13, he did what many people do when they seek answers: He turned to Google. But Trump’s announcement that the Alphabet Inc. unit would be harnessing 1,700 engineers to build a national website to screen people for symptoms, and if necessary direct them to a nearby testing site, was overly optimistic. Google is rushing to rise to the occasion.

Across Silicon Valley, tech companies big and small are stepping up to help in any way they can. Amazon.com Inc. is prioritizing shipments of medical supplies and household staples and plans to hire 100,000 workers to help speed those orders. Facebook, Microsoft, Twitter, YouTube, and others have pledged to work with one another and alongside government agencies to stop the spread of misinformation about the virus.

Tech billionaires are getting involved. Bill Gates, Microsoft Corp.’s co-founder, stepped down from the company’s board to focus fully on his philanthropy and dedicate research to helping stop the virus’s spread. Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. co-founder Jack Ma, working with his philanthropic organizations, has donated millions of dollars to support medical research efforts and disease prevention and has prepared 500,000 testing kits and 1 million masks for the U.S. Smaller companies such as health-care software providers Phreesia Inc. and Buoy Health Inc. are helping medical providers triage potential patients for testing and care.

Every day matters as authorities race to track and slow the virus before it overwhelms the fragmented U.S. health-care system. States are trying to limit the damage from the pathogen, which experts believe could infect at least half the country’s 329 million people, sharply reduce economic and personal activity for weeks or months, and plunge the economy into recession.

There have already been problems with the promised Google website. First, it wasn’t being built by Google exactly, but by a sister company under the Alphabet umbrella, health-care unit Verily Life Sciences. On March 15, Vice President Mike Pence and public health officials followed up with more details. As they explained it, tests were being rushed to sites across the country, and at least 10 states were already running drive-thru testing centers. Pence said Google’s website would tell people whether they needed a test and direct them on to one of dozens of new clinics popping up in Target and Walmart parking lots across the country.

For now, the website is available only in the San Francisco area. And on its first full day of operation, it reached capacity and stopped scheduling new testing appointments. Only 20 people got tested on Day 1, according to a person familiar with the operation. “In these first few days of this pilot, we expect appointment availability to be limited as we stand up operations and that testing capacity will increase in the days to come,” says Verily spokeswoman Carolyn Wang.

The site faced immediate criticism from privacy advocates for its requirement to use a Google account to log in. The company said the step is necessary to keep in touch with patients and that Verily won’t share the data with any other part of Alphabet. Separately, Google plans to launch a website dedicated to information about the coronavirus soon. It also plans to use the site to direct people to a Covid-19 screening tool being developed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In the meantime, state and local health authorities have established hotlines for people to call and speak to a nurse who assesses whether each caller qualifies for testing or not, and labs are increasing their capabilities for running tests. Letting a computer handle the testing triage over the internet would be more efficient, but it’s hard to know yet if the Verily system can even accurately decide who should be tested. “What’s working against Google succeeding is the absolutely impossible timeline and expectations that just got set on them with no warning,” says Michael Slaby, a technologist who helped lead the Obama administration’s effort to fix the disastrous rollout of the Healthcare.gov insurance exchange in 2013. Developing and troubleshooting tech infrastructure during a national crisis was a gargantuan task for Obama’s team, Slaby says: “They didn’t sleep for two weeks. It was incredibly intense.”

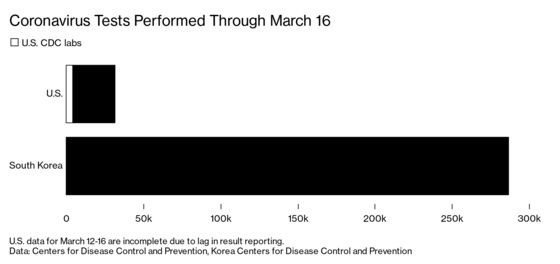

Asia could serve as a model for how technology can be deployed to help in the crisis, but many of the measures used there wouldn’t pass muster in the U.S., where civil liberties are more protected. In South Korea, one of the hardest-hit countries, the government used GPS phone tracking, credit card records, and surveillance video to track the movements of virus carriers and publish them on a public website.

In China, tech giants such as Alibaba and Tencent Holdings Ltd. acted as extensions of the government, helping develop a color-coded health rating system to identify people’s level of risk and monitor their movements. The system, in use at offices, malls, and subways, scans people seeking to enter and allows or denies them access based on their ratings. E-commerce companies were also asked to report the identities of people buying cough or fever treatment in certain cities, while WeChat added functionality so users of its social network could see if they were in proximity to virus cases.

The digital tracking in China and Korea has its own consequences. Lists of people suspected to have the virus, and their contact information, were leaked in China and spread on social media, attracting online harassment. There’s also evidence that the apps from Tencent and Alibaba send personal data to police, which could lead to other human-rights issues.

Even in a time of crisis, such invasive methods might not be legal or acceptable in the U.S. For now, the country will have to make do with the haphazard system it has. “There are going to be people a week from now who are going to say, ‘I tried to get a test but I couldn’t get it,’ ” Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, said in a TV interview on Fox. “But the totality of the picture is going to be infinitely better than it was a few weeks ago.” —With Shelly Banjo

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.