It’s Time to Reclaim the Meaning of the Word ‘Entrepreneur’

It’s Time to Reclaim the Meaning of the Word ‘Entrepreneur’

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Two hundred and ninety years ago, when the French-Irish economist Richard Cantillon first defined an entrepreneur as anyone who worked for unfixed wages, he noted that the one thing that linked all entrepreneurs—from wealthy merchants to beggars—was the risk they shouldered as the price of independence.

That cost is clearly visible on the faces of entrepreneurs everywhere today. Shut down by necessity and starved of customers, many small businesses are bleeding money and fighting to stave off failure. Forty-four percent reported a decline in revenue during the second week in June because of the pandemic, according to data released by the U.S. Census Bureau on June 18. As the boarded-up shops, restaurants, and stores around our neighborhoods already hint at, many won’t survive the crisis.

As a journalist, I’ve devoted my career to writing about entrepreneurs in the pages of this and other magazines, as well as in books, the latest of which is The Soul of an Entrepreneur. I know they’re a resilient bunch. And that gives me hope, because while Covid-19 is ending many small businesses, it’s already creating scores of new ones. The pandemic might have brought American entrepreneurship to the breaking point, but it also holds the key to its revival and a more equitable renewal—if we can get it right this time.

In an election year, you’ll hear politicians of all stripes speak admiringly about the contributions of entrepreneurs. It’s true, there’s strength in numbers: Small and midsize businesses (defined as those with fewer than 500 workers) employ about half of all working Americans and at last count contributed 44% of the country’s gross domestic product, according to government statistics.

Look past the flattering rhetoric and equally flattering figures, and you’ll find a more troublesome trend. Over the past two decades, entrepreneurship saw a strangely paradoxical evolution in the U.S. Culturally it became romanticized, as high-profile tech startups and charismatic young founders disrupted industries and created a new class of capitalist celebrity hero (see Musk, Elon).

You’ve heard the hype: the WeWork offices packed with new startups, the Shark Tank contestants who hit it big, the predictions that millennials would become the most entrepreneurial generation ever. Yet by just about every measure, U.S. entrepreneurship has been steadily decreasing, or flat, for 20 years or more.

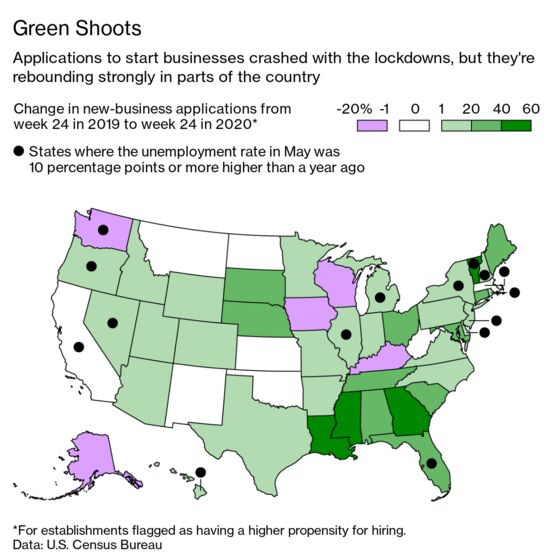

When Ronald Reagan came into office in 1981, 2 in 10 Americans worked for themselves in some capacity. The figure was half that before the 2008 financial crisis, and it’s continued to trend down since. Data culled from paperwork new businesses submit to the IRS tell a similar story: Applications from establishments that are flagged as having a higher propensity for hiring hit a high of about 394,000 in the first three months of 2006, but fell precipitously once the Great Recession hit and have barely breached 330,000 per quarter since. As for millennials, it turns out they’re the generation least likely to become entrepreneurs in a century .

Even before the coronavirus arrived, entrepreneurship never felt less attainable for the majority. Few young businesses start with much capital, and only 17% ever access outside financing. (Most run on savings, family investments, and revenue.) They typically don’t grow very quickly or very much; only 2 in 10 have employees. Economists often cast these entrepreneurs as woefully inefficient, and many have pointed to their decline as a positive sign. If thousands of small hardware stores or taxi businesses are replaced by Home Depots or Uber, this benefits consumers and investors, the argument goes, pushing prices down and profits up, driving innovation, and moving the economy forward.

This is the zero-sum conception of entrepreneurship pushed by Silicon Valley, with its obsessive focus on a few highly successful startups at the expense of the rest. (“Competition is for losers” is a mantra of venture capitalist Peter Thiel.) As the gap grows between the few that can capture markets, tap capital funding, and continue to grow and the majority left to fend for themselves, the foundational promise of America’s equal opportunity through self-starting rings increasingly hollow. The strongest plants may grow into tall trees, but they deprive saplings of sunlight, slowly killing the forest.

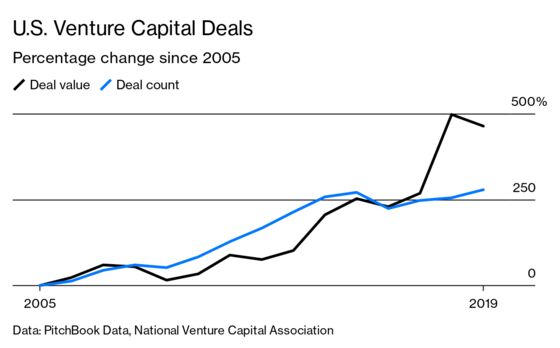

This schism is plainly visible in how venture capital is allocated. In the U.S., the overall pool of money has grown exponentially over the past decade, from $229 billion in 2009 to $443 billion last year, according to data provider PitchBook. But the trend in recent years has been toward bigger checks for fewer superstar startups. Call it the Softbank effect.

And despite all the talk in corporate America of the importance of striving for greater diversity, the message doesn’t appear to resonate in Palo Alto, the de facto capital of the venture capital industry. In 2019, according to Pitchbook, less than 3% of investments went to women-led companies—an all-time high, ladies!—while a report by Diversity VC found that just 1% of VC-backed founders were Black and 1.8% were Latino.

To understand how out of step with the times all this is, consider this: From 2002 to 2012, the number of businesses owned by Black women increased 179%, compared with 52% for all women-owned businesses and 20% for all businesses, according to a recent report from the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, an advocacy organization for entrepreneurs. Yet Black women-led startups attracted just 0.06% of angel and VC funding raised between 2009 and 2017, according to ProjectDiane 2018, a biannual demographic study sponsored by JP Morgan Chase & Co. and the Case Foundation.

There’s also a stark geographic skew: Almost half of all funding in 2019 went to companies in the Bay Area, followed by those in New York and Massachusetts. Even Seattle, home to two of the most valuable technology companies in the world—Microsoft Corp. and Amazon.com Inc.—received only a smattering of VC funds. “The gaps in inequalities that exist today, even in entrepreneurship, will become more amplified unless something changes,” says Wendy Guillies, president of the Kauffman Foundation. She points out that those groups with the highest death rates from Covid-19 (the poor, people of color, rural residents) have also borne the brunt of its economic costs. A paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research in June showed that while the number of active business owners in the U.S. plunged 22% from February to April (representing 3.3 million lost businesses), Black-owned businesses saw a much steeper 41% drop—an unprecedented extinction-level event whose effects will linger for generations.

That’s the bad news, and more is sure to come. The silver lining may be the pandemic’s once-in-a-century opportunity to revive U.S. entrepreneurship. With an historic 21 million Americans out of work as of May, many may choose to become their own employer whether out of need, opportunity, or, more likely, some messy middle. “Just because it’s out of necessity, that doesn’t mean it’s a bad thing,” Guillies says. “Sometimes it takes major disruption to have a rebirth, and I think this is an opportunity.”

But to truly make entrepreneurship accessible to all Americans, some fundamental things must change. The first is education. Entrepreneurship has been one of the fastest-growing fields of study over the past four decades, expanding from a handful of courses in the 1980s at scattered campuses to thousands available today at colleges around the world. Many schools actively promote Silicon Valley-style startups, funding incubators and accelerators, seeding in-house investment funds, or forging partnerships with VC firms that recruit student scouts on campuses to spot the next billionaire lurking in a dorm room.

But a lot of this entrepreneurship education relies too heavily on success stories from wealthy guest lecturers—what a Bloomberg Businessweek article in 2013 called “clapping for credit”—while ignoring the majority of everyday businesses.

The obsession with venture-funded tech startups has been wildly out of proportion to their importance in the real world. A 2017 paper reported that while VC investments and initial public offerings are extremely rare events, affecting less than 1% of companies in the U.S., these two subjects were the focus of almost half of all papers published in entrepreneurship journals. Imagine if half of biologists published research only on elephants, ignoring 99% of the creatures on the planet, says Howard Aldrich, a professor of sociology and entrepreneurship at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, one of the paper’s authors.

For the benefit of larger numbers of students and those with more diverse backgrounds, entrepreneurship education should focus on a wider range of paths for starting a business, including small and midsize companies, multigenerational ownership, and even lifestyle businesses (those set up to support a founder’s living expenses and pursuits, without growing exponentially), rather than focusing on pie-in-the-sky pitches delivered on “demo day” like some half-baked reality show.

The Interise Streetwise “MBA” program, launched by Boston University in 2007, teaches real-world strategies, such as prioritizing contract bids to maximize profitability, to entrepreneurs in inner-city communities. The objective of the seven-month, part-time program is for existing small-business owners to gain the knowledge, tools, and networks necessary to break the cycle of stagnation. Graduates see a 36% increase in revenue, on average, and quadruple the job creation of their peers, according to the program’s managers. Yashieka Anglin, who heads Anglin Consulting, a Washington firm that provides financial services to government agencies, completed a version of the program in 2018 run by the Small Business Administration. “It changed how I looked at my business,” says Anglin, who as a second-generation Black entrepreneur appreciated the diversity of faces in her cohort. She says her “classmates” have continued to support one another during the pandemic, including trading tips on how to secure funds through the federal Paycheck Protection Program and other Covid-related assistance. “It took me from jumping at everything that moves to being more strategic.”

Expanding access to financing should be another priority if the U.S. is to replenish its ranks of small-business owners. According to a 2018 report by the Federal Reserve, the past two decades have seen the number of community banks in rural and urban areas fall by almost half, from 10,700 in 1997 to 5,600 in 2017. That places more capital in the hands of national and global banks, which tend to favor loans of $1 million and more. (Most entrepreneurs seek less than $100,000 in financing, according to another Fed survey.) Not surprisingly, this further entrenches the systemic inequality of entrepreneurship. “I stopped counting the number of times I got rejected by banks when pursuing additional financing to grow my business,” Anglin says.

What we need are more lenders focused on building relationships with business owners in their own backyards. (Think George Bailey from It’s a Wonderful Life reincarnated as a Latina in Albuquerque.) That argues for policies to bolster the number of community development financial institutions (CDFIs), a federally certified form of private financial institution created in 1994 to support underserved communities. There are a scant 1,000 across the country. One of them, the Washington Area Community Investment Fund, extended Anglin a $25,000 loan.

“They were the people who would take a risk on us,” says Jason Amundsen, who owns the Locally Laid Egg Company in Wrenshall, Minn., with his wife, Lucie. The Amundsens used a $320,000 loan from the local branch of the Entrepreneur Fund (a CDFI where Jason once worked), to buy their farm. “I mean, I’ve got 2,000 chickens, and I’m staring down another winter outside in the fields, or I can buy a farm and get a barn and not have those chickens spend winter outdoors,” Amundsen says. “That’s a no-brainer. That’s a lifesaver.”

It’s heartening to see that the financing ecosystem for small business is evolving and now includes a handful of “sustainable” venture capital funds such as Indie VC. Based in Salt Lake City, it invests only in “real” businesses that are on a clear path to profits. Indie features a GIF of a burning unicorn on its website, a jab at the mythic valuations achieved by some startups for which profits remain elusive. Niche lenders of this type are coming together in initiatives such as the Capital Access Lab, a fund designed to seed new financial products and technologies that can directly address the needs of entrepreneurs.

Finally, what small-business owners also need as they try to navigate this crisis is community. The mythology of a maverick genius like Steve Jobs obscures the truth that entrepreneurship can be profoundly lonely. Entrepreneurs need peers they can talk with, who can give them advice and guidance. These bonds may help ensure survival for some and lessen the trauma of failure for others. A recent paper from Germany showed that the psychological effects of losing your business when self-employed are worse than losing a salaried job.

Chapters of organizations such as 1 Million Cups, which brings local entrepreneurs together (virtually for now) for monthly Alcoholics Anonymous-style meetings, are popping up around the nation. Visits have tripled to the online education portal for entrepreneurs run by the National Association of Women Business Owners. Zebras Unite sprang from a 2017 post on the website Medium calling on the founders of startups to create an alternative for entrepreneurship that’s more equitable and ethical than the Silicon Valley startup model. With 5,000 members in 45 chapters on every continent, it now hosts an annual camp and podcast, and helps its members pool their ideas, resources, and fighting spirit to support each other like a herd of zebras (which is called a dazzle, in case you didn’t know).

For too long, we bought into the notion that all we needed to do was create and support the entrepreneurs building the biggest businesses, assuming the trickle-down of money, jobs, and innovation would benefit everyone. But a healthy economy needs a full complement of enterprises: the high-tech, rapidly growing companies and midsize manufacturers; the MBA-educated innovators disrupting markets; and the small businesses run by minorities, immigrants, women, and seniors that make our neighborhoods vibrant. Silicon Valley talks a lot about the “ecosystem” for startups, but we need to remind ourselves that the healthiest ecosystems are diverse. They need microbes and ants—not just elephants.

Mara Zepeda, a co-founder of Zebras Unite, sees the present crisis as a once-in-a-generation opportunity to transform American entrepreneurship. “We’re in this moment right now that feels like Noah’s Ark, and we’re trying to get in two by two. We have to save these community businesses that are vital to our lives and our neighborhoods and are just the heartbeat of who we are,” she says. “This isn’t one of those survival-of-the-fittest moments. It’s not competitive. We have to come together.”

More than anything, we need to restore the belief, so deeply ingrained in America’s identity, that entrepreneurship remains desirable and attainable. So if someone like Anglin is willing to bear the risk Cantillon first wrote about three centuries ago, she can take her idea out into the world and work for herself. “I don’t allow my experience to deter me from moving forward,” she says. “I take the hits and keep going mainly because of my two girls. I’m hoping by the time they get to my age, their experience will be different.”

Read next: A New Crop of Startups Stokes Optimism

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.